(2 PM – promoted by TheMomCat)

At the beginning of last month, Paul Druce of “Reason & Rail” discussed the possible impact of the pending upgrade of the Amtrak Acela route in Acela II is the path towards Amtrak operational self-sustainability:

At the beginning of last month, Paul Druce of “Reason & Rail” discussed the possible impact of the pending upgrade of the Amtrak Acela route in Acela II is the path towards Amtrak operational self-sustainability:

The forthcoming Acela II isn’t just supposed to be significantly faster than the current Acela service, cutting 24 minutes from the scheduled time between Washington and New York and 38 minutes between Washington and Boston, but it will also represent a significant boost in capacity. …

With an increase in seating capacity, Amtrak will be able to garner significantly more revenue, even if it lowers the price of Acela seating somewhat. This added revenue comes with no significant increase in operational cost and quite possibly a lowered cost, as there should be a higher rate of availability and lowered mechanical costs for what is essentially an off the shelf train, along with significantly lower energy consumption. With current averages for occupancy and passenger revenue unchanged, an Acela II train service could see $742 million in revenue, with $447 million in operational profit.

This will have an even larger effect upon Amtrak’s financial deficit than initially appears because starting in FY2014, the states bear a greater responsibility for the short distance train corridors. This had the affect of reducing Amtrak’s FY2014 budget request to only $373 million for the operating grant; 2013’s appropriation, by contrast, was $442 million.

Note that what Paul Druce refers to as “operational profit” is what I have been calling “operating surplus” in the Sunday Train, the surplus of revenues from operations over operating costs. This is nothing like an operational profit, at present, since a profit is a financial benefit from a difference between revenue and costs, and there is nothing in the current organization of the Acela services that make a surplus on their operations into a distinctive financial asset for any purpose … whether public or private.

Whether or not all or part of this operating surplus should be made into an operational profit is a question that goes to the heart of what is the purpose of Amtrak. The way that this surplus is spent can be the means to service a range of ends … but what are the ends that are a legitimate use of these means?

Since Amtrak was established, and exists, as a political compromise, this is not a question about what is the proper “End” for Amtrak activities, but what are the proper “Ends” for Amtrak activities.

The Amtrak Tripod

Amtrak originated, and survives, as a political compromise, with both operational and political complementarity between the three legs of the Amtrak tripod:

- The Northeast Corridor, with operating surpluses overall and quite substantial capital requirements, for Maintenance of Way, for rehabilitation to a State of Good Repair (making good a promise originally made in the 1970’s), and for upgrades to contribute an even more substantial share of intercity transport in a region where the per-mile costs of road capacity expansion can be enormous;

- The State Corridors, with some large metropolitan areas provided with a range of services, some metropolitan areas enjoying one or two valued services, and many metropolitan areas receiving no service at all, previously operating under a range of cost-sharing arrangements reflecting Administration and Congressional philosophy regarding Amtrak at the time the service was established, but recently moving toward a common cost-sharing formula, with federal capital subsidies for most state corridor located outside of the Amtrak budget; and

- The Long Distance services, with substantial operating loss ratios, operating as a combination of skeleton service retaining a vestige of diversity in our long distance intercity transport system dominated by much larger road and air services receiving much larger operating and capital subsidies, and with quite limited needs for ongoing capital subsidy.

The Northeast Corridor is a fundamental concern to the economic health of most of the states through which it travels. Indeed, the majority of trains traveling on the Northeast Corridor are commuter railroads. As discussed in Railway Age in June of 2013,

The states of Delaware, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Virginia currently pay less than full-cost recovery user charges for those commuter trains’ access to the Northeast Corridor. Agreements in place vary considerably as to cost recovery, and Amtrak is a minority user of the corridor it owns.

On the 456-mile Northeast Corridor linking Washington, D.C., with Baltimore, Philadelphia, New York, and Boston, Amtrak operates only 153 trains daily, while commuter carriers operate more than 2,000 trains daily.

Interestingly, freight railroads that operate 70 freight trains daily over the Northeast Corridor do pay Amtrak full-cost recovery under negotiated contracts.

Now, train counts can be as deceptive as trip-counts when comparing longer distance trains and shorter distance trains, but note that even if the average Amtrak route is ten times the length of the average commuter railroad route on the NEC, the majority of route-miles would still be on commuter railroads.

So the current arrangements on the NEC are an implicit subsidy of commuter rail operations in these eight states. There is a currently ongoing process to develop a formula under which commuter railroads using the NEC would pay full cost recovery, but while this would result in an increase in the financial performance of the NEC, there is a substantial risk of an economic loss if cash-strapped states are forced to cut back commuter rail services, generating increased use of our heavily subsidized road network … and of course, increasing financial pressure on these same states.

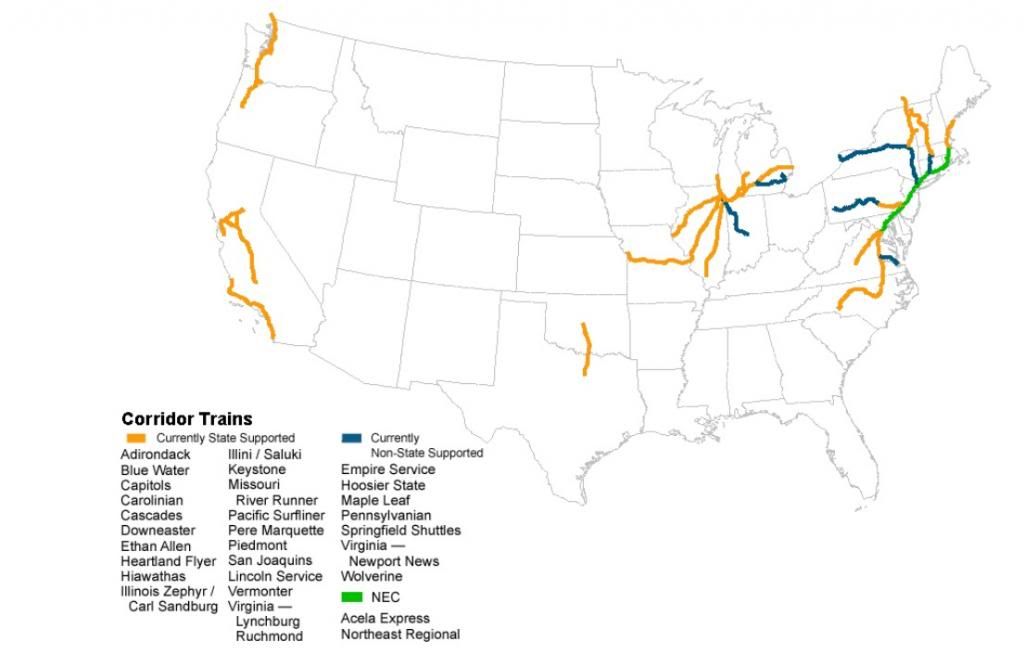

The state corridors are heavily clustered, which helps explain the impetus for the states served bearing the full operating costs of these services. There is a cluster of services in the Northeast that operate onto the NEC, often originating and terminating in NYC, a cluster of services in the Great Lakes and Midwest originating and terminating in Chicago, the three Amtrak California services (Capital Corridor for Northern California, Surfliner for Southern California, and San Joaquin connecting Northern California and the San Joaquin Valley, with a bus extension from Bakersfield into LA), Oklahoma’s Heartland Flyer from OK City to Fort Worth, TX, and the Cascade Corridor serving Washington and Oregon.

The state corridors are heavily clustered, which helps explain the impetus for the states served bearing the full operating costs of these services. There is a cluster of services in the Northeast that operate onto the NEC, often originating and terminating in NYC, a cluster of services in the Great Lakes and Midwest originating and terminating in Chicago, the three Amtrak California services (Capital Corridor for Northern California, Surfliner for Southern California, and San Joaquin connecting Northern California and the San Joaquin Valley, with a bus extension from Bakersfield into LA), Oklahoma’s Heartland Flyer from OK City to Fort Worth, TX, and the Cascade Corridor serving Washington and Oregon.

Some of these corridors were legacy services that were inherited by Amtrak from freight railroads in meeting prior community service obligations, while others were either established or expanded by states by agreement with Amtrak, which helps account for much of the uneven cost sharing. For instance, if three subsidized legacy corridors have been operated by Amtrak with one service per day, and three different states contract with Amtrak to provide additional service, with each state covering the pro-rata share of operating costs for the new services, the result will be:

- 0% state cost share in a state that does not add any state subsidized services;

- 50% state cost share in a state that adds a second, state subsidized service;

- 75% state cost share in a state that adds three, state subsidized, services; and

- 87.5% state cost share in a state that adds seven, state subsidized, service.

At the time of arriving at each contract, each state is making the same underlying deal … “we’ll cover the cost of the extra services” … but the end result is a quite uneven distribution overall. And since the details of the cost sharing in each case depends upon specific contracts as negotiated at different points in time, there will be a wide range of difference as to what costs are included and on what basis.

This was the landscape that “PRIIA Section 209” aimed to reform. One major hurdle to overcome was how to treat those services operating on a few sections of Amtrak-owned corridors, where costs of actual Maintenance of Way spending was substantially higher per route mile than the majority of corridors where freight railroads charged fees for the use of freight corridors by Amtrak. A second was how to charge overhead costs, where states preferred fixed percentage charges with Amtrak bearing the risks of unexpected increases in overhead costs ~ and receiving the financial benefit of improved productivity in overhead operations. Once agreement was reached on a formula for an “as if access fee” for Amtrak-owned corridors and Amtrak agreed to set percentage overhead charges, most states reached agreement with Amtrak regarding the cost-sharing formula.

Indiana objected to the agreement, though without offering an alternative, and the legislation was written with an eye toward agreement by all states … while at the same time giving Amtrak a hard deadline for completing agreements to operate short corridors under the new cost sharing agreement. So Amtrak took the agreement with the majority of states with short corridors to the Surface Transportation Board, which approved it for use. In October, 2013, Indiana reached an agreement to keep the Hoosier State corridor from Indianapolis to Chicago in operation, with the majority of the money for the state share coming from the cities in Indiana along the corridor.

The Long Haul corridors are the fifteen Amtrak services with routes over 750 miles:

The Long Haul corridors are the fifteen Amtrak services with routes over 750 miles:

- The Northeast Corridor to Chicago trains ~ the Lakeshore Ltd from NYC and Boston to Chicago, the Capital Ltd from DC to Chicago, and the three-per-week Cardinal from NYC to Chicago via WV, Kentucky and Indiana;

- The NYC to Southeast trains, discussed last week ~ the Silver Meteor and Silver Star to Florida, the Palmetto to Savanna, GA, and the Crescent to Atlanta and New Orleans, and the “land ferry” Auto Train from Northern Virgnia to Florida;

- The Chicago Western Trains ~ the Empire Builder to Seattle and Portland, the California Zephyr to San Francisco via Denver, the Southwest Chief to LA via New Mexico, the Texas Eagle to Forth Worth and San Antonia; and the City of New Orleans to New Orleans;

- The remaining Western trains, the Sunset Limited between New Orleans and LA and the Starlight (often called “Starlate”) from Seattle to LA via Portland and Oakland.

The same legislation that required Amtrak and the states to arrive at a cost-sharing agreement for short corridor services required Amtrak to study ways to improve the financial and customer service effectiveness of the long haul corridors. The result so far has been modest improvements to the best performing trains and a number of quite more substantial improvements to the worst performers held back by the costs of supporting capital upgrades, according to the host freight railroads, and the unwillingess of Congress to increase total operating subsidies in pursuit of substantial reductions in operating loss ratios and substantially smaller subsidies per passenger mile.

Of course, a tendency to refer to long distance corridors by their end points combined with hazy memories of long distance train travel before the rise of air travel often gives a misleading impression of what the point of the long distance routes are. End to end patronage only accounts for a minority of service, with an average trip of 600 miles, which, depending upon transit speed is a trip of 12-20 hours. So much more common than end-to-end trips are trips between larger metropolitan centers along the corridor and trips between smaller rural areas and larger metropolitan centers.

The Core Compromise

The core political compromise that created the Amtrak system was between the representatives of the large, densely populated metropolitan areas of the Northeast Corridor, middle sized urban centers that relied upon corridor trains to gain access to larger metropolitan centers, and those rural areas relying upon long distance passenger trains as an important part of their access to intercity transport.

The model under which passenger rail service had been provided in much of the country was by mandating passenger rail service as a requirement for operating a railroad on a corridor, which meant that passenger rail service was effectively cross-subsidized by freight rail operations. However, after World War II, we embarked on our long project of providing massive subsidies to air transport and road transport, with substantial cross-subsidies from passenger to freight transport on our motorways laid on top of the overall subsidies to road transport, so subsidy-paying freight railroads that paid full cost plus property tax for their infrastructure were placed into competition with subsidy-receiving road freight that paid only a minority share of their largely property-tax-free infrastructure.

So the post-WWII era represented a long retreat by freight railroads from general freight into the heavy bulk commodity freight where their real cost advantage was so substantial that they could not be overcome by the massive subsidy advantage enjoyed by road freight. And part and parcel of that retreat was that the freight rail system became less and less suitable for the provision of effective conventional rail passenger transport.

Amtrak involved picking up the pieces of the destruction of the foundations of the original passenger rail mandate system with an agreement that if the freight railroads would allow Amtrak to use their corridors, then Amtrak would take over their mandated responsibility to provide passenger rail service.

Of course, over time Amtrak shifted from being a makeshift effort to rescue as much as possible of the benefits of the status quo passenger rail system to itself representing the status quo, so that even as levels of service funded by Amtrak ebbed and flowed with changes in political tides in Washington, we saw the accumulation of the state-subsidized corridor services, and the establishment of the formally-HSR-but-effectively-Rapid Rail “Acela” system in the Northeast Corridor.

Which is the context in which we encounter the question of what to do with the types of operating surpluses projected for the upgraded Acela II services.

As noted by Paul Druce, these surpluses could push the entire Amtrak system close to an operating break-even. On 2013 operating costs of the national train system of about $2,83b, and operating revenues of about $2.39b, that requires an operating subsidy of about $435m (or less than $1.40 per person). However the operating subsidies of the short corridor leg is being substantially reduced, so that simply pooling operating revenues and operating costs between the three legs is, in effect, a transfer from Northeast Corridor operations to long distance rail operations.

Indeed, if we were to go beyond the Acela II system to the $20b NEC High Speed Rail corridor proposed by Alon Levy, the appeal of that passenger service would likely place Amtrak in a position of operating surplus as a whole … even as intercity rail as a whole would still likely require, and merit, substantial capital subsidies.

So, under the current institution of making an operating subsidy request, for all three legs, and a capital subsidy request, for all three legs, the de facto distribution of operating surpluses on the Northeast Corridor is:

- Nearly 100% to long distance rail operating losses, through to breakeven; then

- To be directed to capital investment or other spending, at Amtrak’s discretion including the pressure or opportunities established by whatever level of capital subsidy Congress agrees to provide.

Is this the best way to allocate this operating surplus?

A New Division of the Spoils

If we were to turn the operating surplus on the NEC corridor into an operational profit, by putting it into a distinct flow of funds with programmed revenue shares … how should we program the revenue shares? (Note that this is a thought experiment, since I am not aware of any existing powerful interest group that is pushing for this conversion from operating surplus into operational profit to be made.)

The first split is between the NEC, which generated the operating surplus (as a return on decades of capital subsidies) and the rest of the system. The system of giving every dollar of surplus from the NEC over to partially cover operating losses of the balance of the system, primarily the long distance rail system is problematic. One of the major problems is that it acts an incentive for cost padding withing the NEC system … with the comparison of Alon Levy’s price tag of under $20b for a 4hr Boston to DC system versus the Amtrak price tag of $150b+ for a 3hr Boston to DC system being a possible example in the differences in mindset between “what costs are required” and “what costs can we find a justification for?”

The split itself is largely arbitrary, but the simplest arbitrary split to explain is the 50:50 split. “Equal shares” carries a sense of being fair. Of course, it often drives a fight to determine who counts as an equal party to get a share, but the current status quo creates a notional two party transaction, with the NEC as contributor of the internal cross-subsidy as one notional party and the rest of the National Train System, as beneficiary of the internal cross-subsidy, as the other.

Within the NEC portion, I would dedicate the bulk to investment in capital improvements, and the balance to defray operating costs of the commuting rail services sharing the NEC. Obviously what “the bulk” amounts to is also a bit arbitrary, but I would suggest an 80:20 split as a starting point.

For the rest of the national system, I would put the bulk into a fund for capital improvements on long distance Amtrak corridors that would contribute to reduced operating losses. However, I would set aside a share for an FRA-administered fund for feasibility studies and environmental impact assessments for improved or new intercity rail corridors. The purpose of this fund would be to build up a national “shelf” of profits that could be pursued in four to ten year timelines as opposed to the twelve to twenty year timelines that presently face corridors without planning already in progress.

Again, what “a portion” amounts to is a bit arbitrary, but I would start with the same 80:20 split as in the NEC share.

Now, this system would mean that Amtrak as a whole would not get “close to” operating break-even as under the status quo system, in which every dollar of NEC operating surplus goes toward operating losses elsewhere, which is largely operating losses of long distance trains.

On other hand, a large part of the prospective value of the long distance rail network is the insurance value of keeping the corridors up and running, in the event that it becomes important to substantially increase our reliance on long distance rail transport. We know that we are going to be facing emergencies over the coming half century, given our multiple, collective decisions over the past three decades to allow the Climate Suicide Club to continue the drive to catastrophe. Having ongoing operations on the corridors currently in use provides some service of substantial importance to a number of smaller communities along the corridors themselves. However, the most valuable service on a national basis is the effective insurance due to continuing to operate the corridors.

Given an insurance premium of under $1.40 per person, where a large part of that premium simply offsets the competitive impact of the massive subsidies given to road transport, I am not persuaded that cutting that insurance premium as low as possible as fast as possible is the highest priority use of the operating surplus on the NEC.

In the notional scheme presented here, 80% of the operating surplus is re-invested in capital works, 10% is devoted to defraying the cost of operations on the NEC by the large number of commuter operations using the line, and 10% is devoted to building up our shelf of completed feasibility studies, approved Tier I Environmental Impact Studies, and approved Tier II Environmental Impact Studies and Preliminary Design and Engineering for intercity rail projects across the country.

On Paul Druce’s figures, that would yield about $100m to each capital fund and $25m to the smaller funds (a little more, given that Paul Druce looks at the Acela alone, and the NEC regional also generates an operating surplus, though smaller). $100m annually to service 5% coupon bonds would be a capital value $1.5b over 20 years.

However, on his projection of Acela II operating surpluses, that would rise to about $300m/yr per capital fund (which could fund $4.5b in bonds with a 5% coupon over 20 years) and around $75m/yr to the two smaller funds.

And I would expect all four streams of funding would be better spent than simply shifting long distance service operating losses from national funding to being funded by surpluses drawn from passengers on the Northeast corridor.

Conclusions & Considerations

As always, the end of the Sunday Train essay is not the final word, but the invitation to start the conversation. Remember that any aspect of sustainable transport policy is fair game for conversation.

However, note that having spent some hours writing about this topic, I may tend to see some other topic as being a commentary on this one. Therefore, please flag that you are raising a different topic when doing so, such as with “NT” for “New Topic” in the subject line.

1 comments

Author

Don’t you know me? I’m your native son.