(2 pm. – promoted by ek hornbeck)

cross-posted from Voices on the Square

Last week, I considered the concept of Pedal to the Metal Climate Change policies: the kind of policies that we will now have to pursue if we become serious about Climate Change, because of the 16+ years we will have wasted since 2000 that would have given us the opportunity to pursue a more gradualist approach. At that time, there was a debate that could be characterized as an argument between “incrementalism” and “purism”. However, at present, and therefore by the time the current administration will be completed, we have passed the point of asking “how fast should we go”, and have passed into “how fast can we go” territory. Hence the Pedal to the Metal approach.

Last week, I considered the concept of Pedal to the Metal Climate Change policies: the kind of policies that we will now have to pursue if we become serious about Climate Change, because of the 16+ years we will have wasted since 2000 that would have given us the opportunity to pursue a more gradualist approach. At that time, there was a debate that could be characterized as an argument between “incrementalism” and “purism”. However, at present, and therefore by the time the current administration will be completed, we have passed the point of asking “how fast should we go”, and have passed into “how fast can we go” territory. Hence the Pedal to the Metal approach.

Last week, I did not rehash Micheal Hoexter’s overview of a Pedal to the Metal Climate Change policy, but rather looked at the leading edge of that policy package, what I dubbed “front-runner” policies, and looked the Steel Interstate as one example of a front-runner policy for a Pedal to the Metal Climate Change policy package. This week, I am going to turn from Rapid Freight Rail and consider what kind of Rapid Passenger Rail policy would qualify as a front-runner policy for a Pedal to the Metal Climate Change Policy.

Rapid Passenger Rail as a Front-Runner Policy for a Pedal to the Metal Policy Package

The foundation of my argument are five features that, singly and in combination, make a policy action suitable to play a front-runner role in this kind of Climate Change Policy Package. Refer back to part 1 for more detailed argument as to the importance of each of these five features:

- Speed of project roll-out: A ten year project with concrete results in five years or less.

- Self-reinforcing: The results of the project as it is rolled out supports continuation of the project

- Cross-reinforcing: The results of the project as it is rolled out support other elements of a Pedal to the Metal policy package.

- National in scope: The project should be able to be pursued on a national basis.

- Multiple Benefit: the project should be able to deliver benefits that are valuable independent of the benefit to Climate Change.

Central to these five features is not just achieving a climate change policy coalition that can get the ball rolling, but a coalition that is fueled in part by the early results of the policy package, since a Pedal to the Metal policy approach requires holding the Pedal to the Metal policies in place for 15-20 years. Any set of policies that are adequate to the task will be disruptive to the status quo and therefore will generate substantial pushback and ongoing efforts to undermine and sabotage the policy package in service to the Climate Suicide Pact and their political allies.

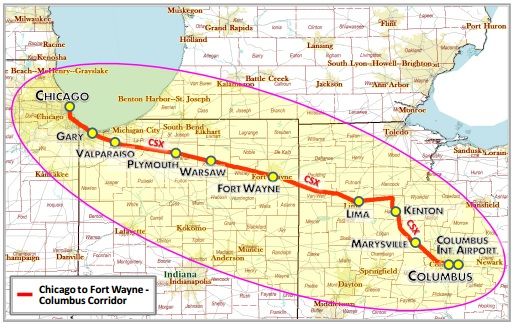

So, what is Rapid Passenger Rail, and does it qualify? Sunday Train has recently covered two different examples of Rapid Passenger Rail projects: the Miami to Orlando project currently hoping for a 2015 start of service, and the Chicago / Fort Wayne / Columbus project proposed by the Northeast Indiana Passenger Rail Association (NIRPA). As the private Miami to Orlando venture requires on a particular combination of out of state tourists engaged in in-state intercity travel and real estate development opportunities for multi-use stations / retails / residential development, I will be using the Chicago to Columbus proposal as a more typical project.

So, what is Rapid Passenger Rail, and does it qualify? Sunday Train has recently covered two different examples of Rapid Passenger Rail projects: the Miami to Orlando project currently hoping for a 2015 start of service, and the Chicago / Fort Wayne / Columbus project proposed by the Northeast Indiana Passenger Rail Association (NIRPA). As the private Miami to Orlando venture requires on a particular combination of out of state tourists engaged in in-state intercity travel and real estate development opportunities for multi-use stations / retails / residential development, I will be using the Chicago to Columbus proposal as a more typical project.

NIRPA is an advocacy group, and while the Chicago to Columbus via Fort Wayne corridor is not a funded project, NIRPA was able to fund the completion of a feasibility study and business plan (pdf: executive summary). They study two levels of potential service, a 110mph version and a 130mph version, but given the high capital cost of an all grade-separate corridor required for the 130mph version, they focus on the a 110mph version of the corridor with a total capital cost of $1.3b, or about $4m/mile. As noted in that 1 September diary, multiple estimates of the cost of electrifying the Keystone West corridor in Pensylvania through rugged Appalachian terrain place the cost at less than $3m/mile, so even if the average cost for rail and rolling stock is $7m/mile, we can expect to build an electrified Rapid Passenger Rail system at an average cost of $10m/mile or less.

This type of project qualifies for prospective speed of roll-out. Given an appropriate level of funding, a corridor of this length can be completed in a year for the preliminary Environmental Impact Report and two years for construction. By spreading projects around the nation, we could be initiating five corridors a year over an eight year period, which would be a total of 12,000 miles of upgraded intercity rail corridor.

It is also self-reinforcing. Connecting corridors together, either lengthwise or along a hub, offer transport connections that build demand for the corridors. Service on a well-chosen 110mph corridor of this type generates an operating surplus, so that the additional transport demand from connecting service increase the operating profit on this corridor, which can be used to finance Revenue bonds for the improvement of these corridors and construction of additional corridors.

This policy is potentially national in scope. Given substantial federal support, there are prospective 110mph corridors in the Northeast connecting to the Northeast Corridor; in the Southeast from Virginia to Florida via the Carolinas, to New Orleans via Atlanta, and to Memphis; in the Great Lakes / Midwest in the Chicago and Ohio Hubs; in the Great Plains / Rockies in Texas and along the Front Range; in California routes complementing the bullet train CHSRA system; and in the Pacific Northwest along the Cascades corridor. The total capital cost would be $15b annually, and unlike the Interstate Highway System, the investment would not put federal, state and local governments on the hook for a never-ending flow of ongoing operating subsidies.

This policy is potentially national in scope. Given substantial federal support, there are prospective 110mph corridors in the Northeast connecting to the Northeast Corridor; in the Southeast from Virginia to Florida via the Carolinas, to New Orleans via Atlanta, and to Memphis; in the Great Lakes / Midwest in the Chicago and Ohio Hubs; in the Great Plains / Rockies in Texas and along the Front Range; in California routes complementing the bullet train CHSRA system; and in the Pacific Northwest along the Cascades corridor. The total capital cost would be $15b annually, and unlike the Interstate Highway System, the investment would not put federal, state and local governments on the hook for a never-ending flow of ongoing operating subsidies.

I must stress (from past comment thread experience) that national in scope does not imply setting out to build a transcontinental system. While electric Rapid Freight Corridors would be built to form a transcontinental system, intercity Rapid Passenger Rail corridors focus on linking medium sized cities to each other and to larger metropolitan centers along corridors of 300miles. We should interconnect those corridors where practicable, to gain the benefit of connecting transport demand, but each corridor should be built with an eye to achieving an operating surplus based on the transport demand within that corridor.

I will also stress that while this figure sounds large based on previous experience, the topic at hand is building a policy as part of a Pedal to the Metal Climate Change policy package. Relative to a full-fledged Pedal to the Metal policy package, this is a relatively modest slice of the total.

These corridors have multiple benefit. We know that the these corridors offer transport benefits to intercity travelers in these areas, because the projection of ridership is based on actual passenger demand experience of intercity rail corridors in the United States and how patronage reacts to increases in reliability, frequency and transit speed, so we know that the improvements to intercity rail that these investments make possible are valued by a portion of the traveling public. And if they are built as electrified passenger rail corridors, they offer substantial de facto insurance against crude oil price shocks and crude oil supply interruptions. But despite the fact that they are warranted public investments, they also offer a substantial range of economic benefits to stakeholders in the private sector. For the single Columbus to Chicago rail corridor, these include:

- $700m per year additional household income;

- the equivalent of 26,800 full time jobs over thirty years (806,000 “person-years” of work); and

- $2.6b in new joint development opportunities along the corridor

Spread this across 40 corridors, and that is 1m new jobs, $28b in additional annual household income and $100b in new joint development opportunities.

Cross-Benefits from Rapid Passenger Rail

A particular strength of a national roll-out of electric Rapid Passenger Rail corridors is the cross-benefit to other sustainable transport policies.

A particular strength of a national roll-out of electric Rapid Passenger Rail corridors is the cross-benefit to other sustainable transport policies.

In local transport, this is especially important in outer suburban, small town and rural areas that receive a Rapid Passenger Rail station. A pressing problem in small town and rural public transport is the ability to subsidize fixed-route public transport, even where there is a need during the peak commuting period, because of very low ridership per vehicle during off-peak periods. An intercity train station offers an anchor for these services, and can bring marginal routes over the threshold to viability.

An intercity train station also offers an anchor for investment in Active Transport, both walking and cycling. Investment in a complete network of 35mph roads to allow Neighborhood Electric Vehicles to directly reach an adequate range of destinations may be beyond the reach of a small town, but combined with the destinations accssible by train, a general 35mph speed limit for the small town itself and establishment of a few key paths to supermarkets or employment centers may be sufficient.

An intercity train station with charging stations for electric vehicles ~ whether highway-capable electric cars, Neighborhood Electric Vehicles or ebikes ~ doubles the effective range of the electric vehicles from their round-trip range to their one-way range, with their vehicle charged and waiting for them on their return trip.

Rapid Passenger Rail and Bullet Trains as Best Friends Forever

A particular beneficiary from this package would be bullet train systems. While Rapid Passenger Rail primarily draws its patronage from motorists, a well chosen 220mph bullet train corridor of up to 500miles draws from motorists and air passengers in equal measure. However, bullet train corridors are much more expensive than Rapid Passenger Rail upgrades of existing rail corridors ~ compare over $100m/mile for the CHSRA system to $10m/mile ~ and constructing all new, all-grade separated rail corridors takes substantially more time, even if the project is fully funded from the outset.

And a particular challenge for bullet trains is gaining access to the centers of large urban areas. The California HSR system would be substantially less expensive if there already existed electrified Rapid Passenger Rail access from the edge of the Bay Area into the Transbay Terminal, or from the edge of the LA Basin into LA Union Station. Being steel wheel on steel rail technology, bullet trains can junction onto Rapid Passenger Rail corridor … so long as that Rapid Passenger Rail corridor already exists.

Indeed, the first French “TGV” bullet train corridor, from Paris to Lyon not only ran an operating profit, but actually covered its capital costs from its operating profit, largely because it was able to use existing Intercity Express corridors to access downtown Paris and downtown Lyon. The TGV system to this day focuses on constructing 220mph express rail corridors in regional areas outside the large cities, using the Express Intercity network to gain access into the large cities themselves.

To give an example of the benefits to bullet train services offered by a broad national investment in Rapid Passenger Rail corridors, consider HSR from New York to Chicago.

New York to Chicago is not one of the five highest priority corridors in the country for 220mph HSR under current conditions. That is despite the substantial transport market between the two cities, and because of the 4hr travel time. A rail travel time of 3hrs or less makes the service far more competitive for same-day trips, so that a 3hr HSR corridor will typically attract about 40% of the total air/train transport market and a 2hr corridor will typically attract 70% of that total market. A rail travel time of 4hrs or more typically attracts a substantially smaller share of that total travel market.

However, consider a New York to Chicago HSR corridor built in stages, with the Chicago Hub and Ohio Hub already in place. An alignment from New York connecting to the Empire Corridor between NYC and Albany runs through northern Pennsylvania. It crosses the Cleveland/Pittsburgh Rapid Rail corridor south of Youngstown. It runs through Northern Ohio between Arkon and Canton, with an Akron/Canton airport stop, then crosses the 3C (Cleveland/Columbus/Cincinnati) corridor west of Akron. It continues through Northern Ohio, and crosses the Columbus / Detroit corridor south of Toledo. It continues to connect to the Columbus / Chicago corridor at Fort Wayne, with the corridor upgraded to a 220mph, all grade separated corridor through to Gary, where it runs through to Chicago on the 110mph Rapid Rail corridor.

However, consider a New York to Chicago HSR corridor built in stages, with the Chicago Hub and Ohio Hub already in place. An alignment from New York connecting to the Empire Corridor between NYC and Albany runs through northern Pennsylvania. It crosses the Cleveland/Pittsburgh Rapid Rail corridor south of Youngstown. It runs through Northern Ohio between Arkon and Canton, with an Akron/Canton airport stop, then crosses the 3C (Cleveland/Columbus/Cincinnati) corridor west of Akron. It continues through Northern Ohio, and crosses the Columbus / Detroit corridor south of Toledo. It continues to connect to the Columbus / Chicago corridor at Fort Wayne, with the corridor upgraded to a 220mph, all grade separated corridor through to Gary, where it runs through to Chicago on the 110mph Rapid Rail corridor.

Consider the range of direct services that this corridor supports:

- New York / Chicago, of course

- New York / Detroit via the Columbus/Detroit corridor

- New York / Columbus-Dayton-Cincinnati via the 3C corridor

- New York / Cleveland via the Cleveland/Pittsburgh corridor

- New York / Pittsburgh via the Cleveland/Pittsburgh corridor

- Chicago / Toledo-Detroit via the Columbus / Detroit corridor

- Chicago / Columbus via the Columbus / Detroit corridor

- Chicago / Cleveland via the 3C corridor

- Chicago / Pittsburgh via the Cleveland / Pittsburgh corridor

- Chicago / Erie-Buffalo via the 3C corridor

At $50m to $150m per mile, an HSR rail network connecting all of these cities would be quite expensive and, even more critically for a Pedal to the Metal policy, likely take 20-30 years to complete.

However, given an appropriate network of Rapid Rail corridors for a set of cities this size and distances apart, staying on a single HSR corridor as long as possible and then completing the trip on a 110mph corridor that can be used with far better reliability and frequency than it possible today for Amtrak trains running on coal and long distance container train corridors.

And unlike the “empty map” approach to bullet trains, connecting onto an existing Rapid Rail corridor means that the bullet train corridor can be put to effective use in stages, long before the corridor is completed all the way between New York and Chicago.

So the cross-benefit criteria for front-runner policies make investment in a broad range of Rapid Passenger Rail corridors particularly appealing as a front-runner policy. The cost effectiveness of the Rapid Rail corridors , with better peak passenger capacity at less than per mile cost of new divided Interstate Highway, allows us to roll out over ten thousand miles of Rapid Passenger Rail corridor in under a decade. Based on the Chicago/Columbus corridor with a local station every 25-30miles, that offers 400 new anchors for local sustainable transport services, many of them in small town and rural areas where a self-supporting sustainable transport anchor is particularly valuable.

And investing in Rapid Passenger Rail corridors around the country also provides a substantially improved platform for the roll-out of bullet train HSR services.

Conversations, Considerations and Contemplations

So I argue that a policy of investing in a Rapid Passenger Rail corridor system on this scale qualifies for consideration as a front-runner policy for a Pedal to the Metal Climate Change policy package.

And now, as always, rather looking for a more ringing conclusion that that, I now open the floor to the comments of those reading.

If you have an issue on some other area of sustainable transport or sustainable energy production, please feel free to start a new main comment. To avoid confusing me, given my tendency to filter comments through the topic of this week’s Sunday Train, feel free to use the shorthand “NT:” in the subject line when introducing this kind of new topic.

And if you have a topic in sustainable transport or energy that you want me to take a look at in the coming month, be sure to include that as well.

1 comments

Author

We are already being burned … it is time to wake up.