(4 pm. – promoted by ek hornbeck)

Last week, I came across a post at People for Bike, called Four Simple Lessons from Austin’s Brilliant Bike Plan Update … and after reading the post, I clicked on through to the overview of the Bike Plan Update that they were referring to, and it was even better than they said. Once I saw that, I know that Sunday Train was going to talk about both Austin’s Awesome Bike Plan and the Four Key Lessons that People for Bikes draw from it:

- 1) The point of bike plans isn’t to appease bikers, it’s to make bikes useful to everyone.

- 2) Good biking makes good transit better.

- 3) You’re not going to turn every long car trip into a bike trip – all you have to do is turn short trips into bike trips.

- 4) A good bike network increases the capacity of your entire road system.

So follow me below the fold to consider both these four important points and also the general Awesomeness of Austin’s Bike Plan Update.

The Point of Bike Plans is to Make Bikes Useful for Everyone

The point of a Bike Plan is to make Bikes useful for everyone. When taken seriously, that is tremendously useful in avoiding both a narrow plan that only caters to one type of cyclists, and in avoiding thinking of the Bike Plan as a kind of minority-interest pandering component of transport planning.

The point of a Bike Plan is to make Bikes useful for everyone. When taken seriously, that is tremendously useful in avoiding both a narrow plan that only caters to one type of cyclists, and in avoiding thinking of the Bike Plan as a kind of minority-interest pandering component of transport planning.

“Useful to” does not mean “potentially useful to”, or “conceivably useful to”, it means actually useful to, and directs us to think about the full range of ways that a cycle path can be useful. And “everyone” means just that. It means that all classes of cyclists are considered. And it means that benefits to having a cycle network to all other transit users are also considered.

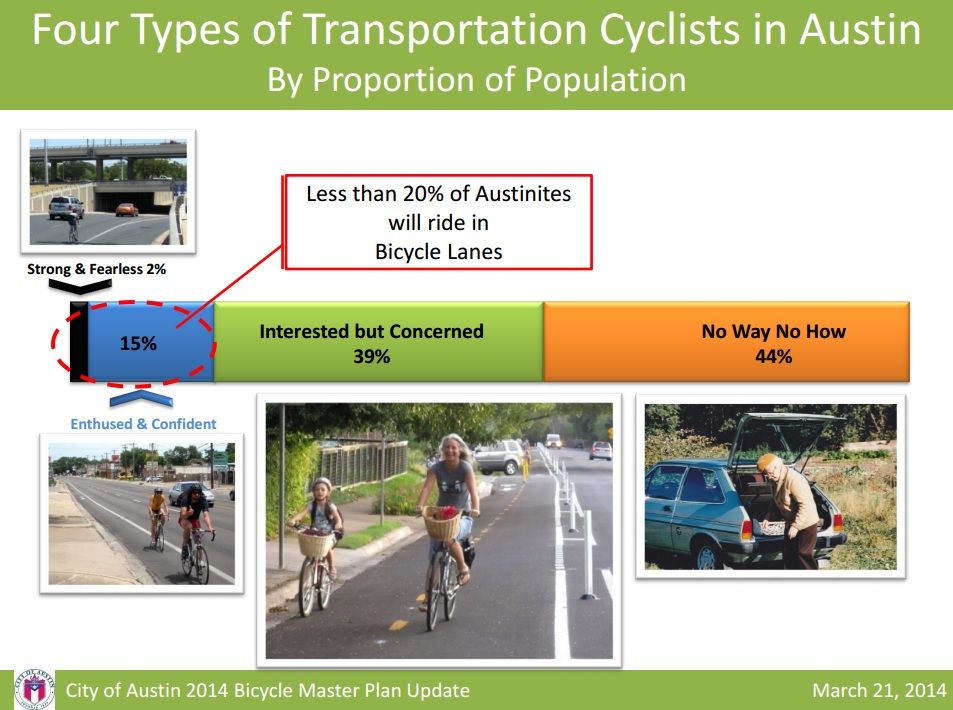

The slide above and to the right is taken from the slideshow developed by Austin Engineer Nathan Wilkes focuses in on the first point. It identifies four types of transport cyclists, with estimated shares among the total population (not just the current cycling population):

- The strong and fearless cyclist, accounting for about 2% of the Austin population. These are the cyclists that will take their legally entitlement to ride in the public right of way, and will, for example, “take the lane” when required for safe riding (indeed, a minority of these cyclists will even take more than their legal entitlement to ride in the public rights). While these cyclists do not require a dedicated bike infrastructure, they do indeed benefit from it;

- The enthused and confident cyclist, accounting for about 15% of the Austin population. These are people who may not be comfortable riding in a general traffic lane with heavy automobile traffic, but are comfortable riding on unprotected cycle lanes and on side streets with lighter traffic.

- The interested but concerned cyclist, accounting for about 39% of the Austin population. These are people who are reluctant or unwilling to ride without protection from higher speed or high volume automobile traffic, but willing to cycle in protected lanes or on streets with light automobile traffic traveling at low speed;

- The No Way No How cyclists, accounting for about 44% of the population. These are people who will not bike, but will rely exclusively on some other means of transport.

-

While a system of painted, unprotected cycle lanes accessed by the regular system of side roads caters to only one fifth of the Austin population as prospective cyclists, a system of protected and buffered cycle lanes and cycleways accessed by a system of side roads including appropriate traffic calming features directly caters to a majority of the Austin population as prospective cyclists.

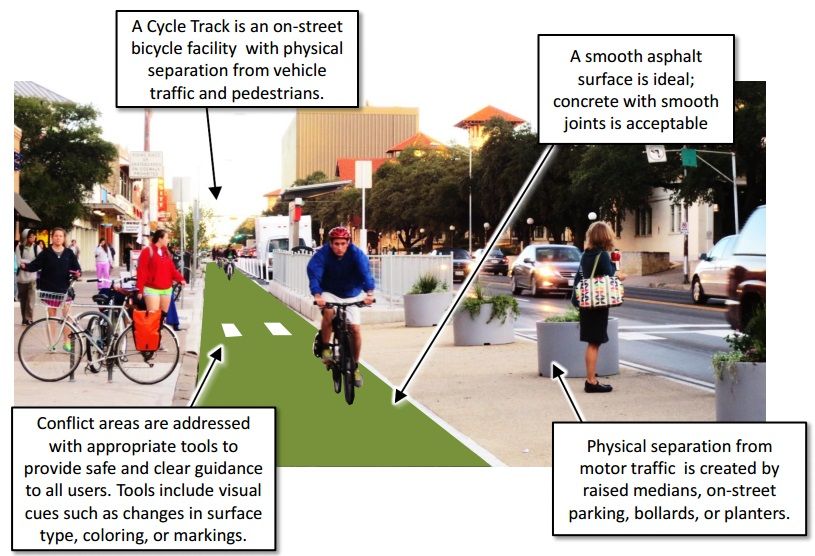

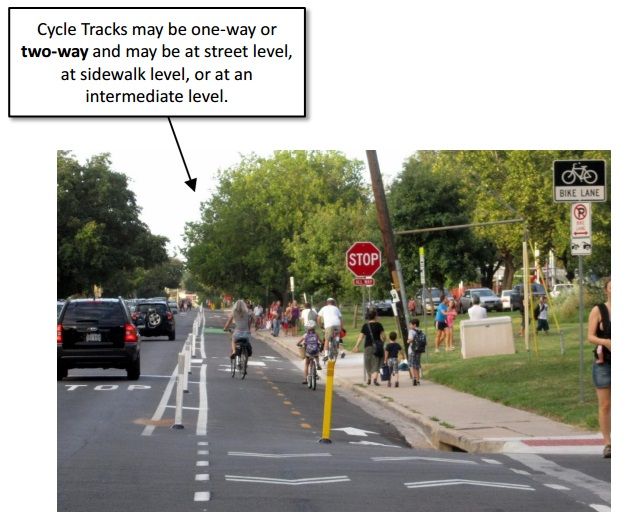

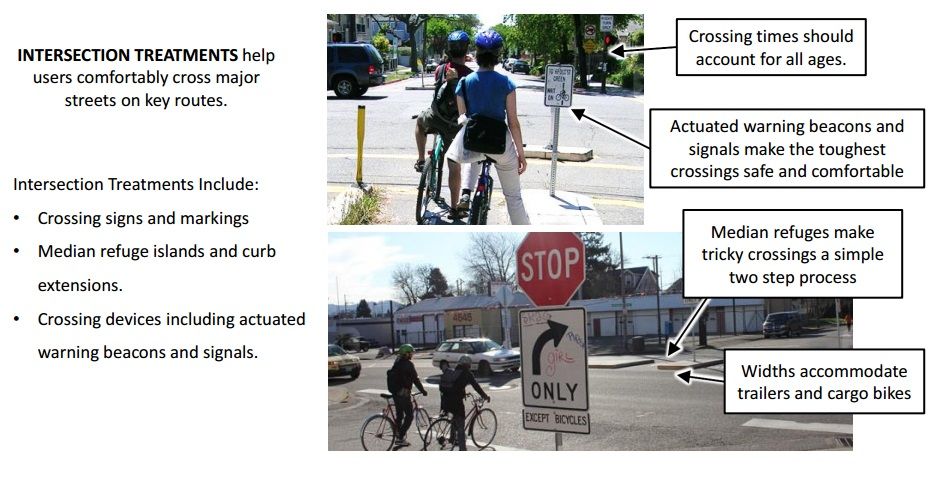

And important part of the Austin cycle network is the “8-80 test”: “An 8 year old traveling with an 80 year old should be able to traverse the city comfortable and safely.” The system has a design speed of 10-15mph, to accommodate commuter cyclists. The design bicycle includes tandems, trail-a-bikes, trailers, and cargo bikes.

To target not just every type of rider and their bike, but also riders across the Austin area, the target spacing between designed bike routes for the completed network is 1/2 to 3/4 mile in the central city and near transit stations, where short trips are most common, with increase spacing further away, with routes designed to connect residences to major employment, retail and educational centers.

And what about the 44%? After all, they may not be a majority, but addressing the needs of everyone means everyone, not “50% plus one”. We’ve already seen that in lessons (2) and (4). An effective bike network makes good transit better, and that benefits all transit users, whether or not they bike. And an effective bike network increases the capacity of the road system, which benefits all drivers, whether or not they bike.

A Well Designed Bike Plan Makes Good Transit BetterIt is the central challenge of all common carrier transport in a passenger transportation system dominated by cars: to serve people, you need to stop, but when you are stopped, you are not moving, and so neither serving the people already in the vehicle headed past that stop, nor the people waiting to board the vehicle further along the route.

When you increase the number of stops on the route, you increase the number of residences and trip destinations within walking distance of the stops on the route, but reduce the effectiveness of the route by increasing transit time. When you increase the number of stops on the route, you increase the quality of service for those served, but at the cost of reducing the total area served in the immediate vicinity of a stop. This trade-off is why some systems offer both Express services connecting the highest demand origins and destinations and all-stops services that offer a wider variety of distinct trips while acting as both a collector and distributor for the Express services at the express stops.

An effective bike network can expand the reach of any transit stop. Where a transit stop has received additional investment, such as shelter from the weather, automated ticket machines, and time of arrival displays, adding cycle parking and cycle lockers leverages that investment by allowing the cycle network to work as an additional local collector and distributor.

This can be especially effective in suburban areas that are a particular challenge for transit planning because of the low density of residences and trip destinations. As the figure above illustrates, where the primary walking service radius of a transit stop is 1/4 to 1/2 mile, the typical cycle service radius is 2 miles, from four to eight times as far. And since the area served is the square of the service radius, that means the typical service area covered is from 16x to 64x the area.

And here is where the first point interacts productively with this one. In a stop serving suburban residential neighborhood with no distinct housing clusters, if 20% of the prospective population are willing to use the type of bike facilities provides, the available leverage from cycle transport would be about 3x to about 12x. If, by contrast, half of the prospective population are willing to use the type of bike facilities provided, the available leverage from cycle transport would be from 8x to 32x.

Now, this is not saying that the bike network will result in from three times to eight times as many trips. After all, “willing to use” is not the same as “willing to use in all weather”, or “willing to use for all trips”. An effective bike plan will not be based on back of the envelope calculations: it will be based on data-driven estimates of responses to the availability of different types of bike facilities for all types of trips.

Indeed, a good cycle network does not on its own convert an inadequate, ineffective transit system into a good transit system.

However, when a local area has made the investment into developing a good transit system, so that access to the transit system becomes a desirable feature for an appreciable share of the population, an effective bike network can build on that foundation and extent the reach of the transit stops. That turn increases the variety of residences and destinations accessible via the transit system, which will lead to an increase ridership. And that, in turn, will result in better financial performance of the transit system, enabling the same amount of public funding to go further and provide services with greater frequency, reach, and/or longer service day.

Bikes support short trips, and supporting short trips is quite useful in its own right.One objection that may be made about “serving everyone” is that most people are not going to take a large number of long trips by bike. But that is confusing “serving everyone” with “serving every trip”. Many people under-estimate what transport cycling can actually do. Still, transport cycling is not a one-size-fits-all solution that is going to meet every passenger transport task in a city.

However, as the data-driven analysis behind the updated Austin Bike Plan shows, serving short trips offers a substantial benefit in its own right. As People for Bikes explains:

When people have comfortable options for every mode of travel, they naturally choose the right vehicle for the right trip. Wilkes used actual behavior patterns from the Netherlands to make this chart of “attainable” targets for Austin if it has a comfortable biking network where people currently take many short trips. Austin’s draft analysis estimates that a protected bike lane network would make bikes the vehicle of choice for 15 percent of trips under three miles and 7 percent of 3-9 mile trips, far below nationwide levels in the Netherlands (pictured).

When put in those terms, the target transport cycling share is quite reasonable. 15% of trips under three miles can be done if a tenth of those willing to use use a perceived safe and secure bike network for use bikes for effectively all of their short trips (5% of the population, 5% of the short trips), a further fifth use bikes for half of their short trips (10% of the population, 5% of trips), and a further half of those willing to use the bike network use bikes for a fifth of their short trips (25% of the population, 5% of trips). The 7% target for trips of 3-7 miles would be met if those same three groups of dedicated, regular, and occasional transport cyclists used bikes for 80%, 20% and 4% of those trips (respectively).

This is a specific application of a general principle of sustainable transport: we are looking for solutions that fit their own needs well, not for one-size-fits-all solutions.

An Effective Bike Network Increases Road CapacityAs Bikes for People say:

The really groundbreaking thing about Austin’s current bike planning is that it expresses the benefits of biking largely in the language of engineers: it looks at bikes as a way to increase the number of trips a congested road system can carry.

And it’s very persuasive.

This is critical. Even in a sustainable transport system, there are still likely to be people in cars, whether powered directly by sustainable electricity, indirectly by fuels derived from sustainable electricity, or from sustainable biofuels (rather than the dirty biofuels that are more common today). And if effective bike networks are going to be a leading edge sustainable transport policy, then it has to attract support among motorists who today cannot imagine actually riding the bike.

But the key here is the difference in the prospective population willing to use protected bike ways, buffered bike ways, and to ride bikes sharing streets with light automobile traffic traveling at relative low speeds. Far more cyclists fit into normal car lane than car passengers. So if providing bike facilities gets enough other people out of their cars, its a net win for the person who is still driving.

The question for the motorist is that when you consider the cyclists in each of these protected cycle paths:

- Would you rather they be in a car in front of you instead?

And that’s a key message to drive home: an effective bike plan is for everyone in any congested area, because the features that make some people want to ride a bike on it are exactly the features that take the cars that they would otherwise drive off the road. So whether you are already on the bike, decide to get on the bike, or remain in the transport you are already using … you are better off.

Provided its an effective bike plan. For example, like Austin’s Awesome Updated Bike Plan.

Conclusions & ConversationsAs always, any topic in sustainable transport is on-topic in the Sunday Train. So feel free to talk about CO2 emissions reduction, energy independence, suburban retrofit and reversing the cancer of sprawl over our diverse ecosystems, or the latest iPhone or Android app to map you bike ride. Whatever.

And on this particular topic, what upgrades would you like to see in a Bike Plan in your own local area?

The Sunday Train doesn’t really leave the station until you jump in and join the conversation so … All Aboard!

1 comments

Author

… its not the …

… no matter how much I may like to #Yell4Cadel …