I have ridden the Beijing Subway and lived to tell the tale!

Click through for scary youtube clip of the Beijing Subway

Of course, the youtube clips you might be able to find about incredible overcrowding on the Beijing subway is just part of the story. Indeed, when riding on my “home” subway line, I often not only find plenty of standing room on the train … I often get a seat.

So follow me as I wander through the Beijing Subway System, below the fold.

A New Line Opens in Haidian District

To be clear, I’m not normally fighting the morning rush hour crowds, since my “commute” to work is to walk about 15 minutes from my apartment at the north side of our campus to my office at the southeast side or a classroom on the southwest side. Even so, morning rush hour at my home station is nothing like this scene at Xi Erqi station on Line 13.

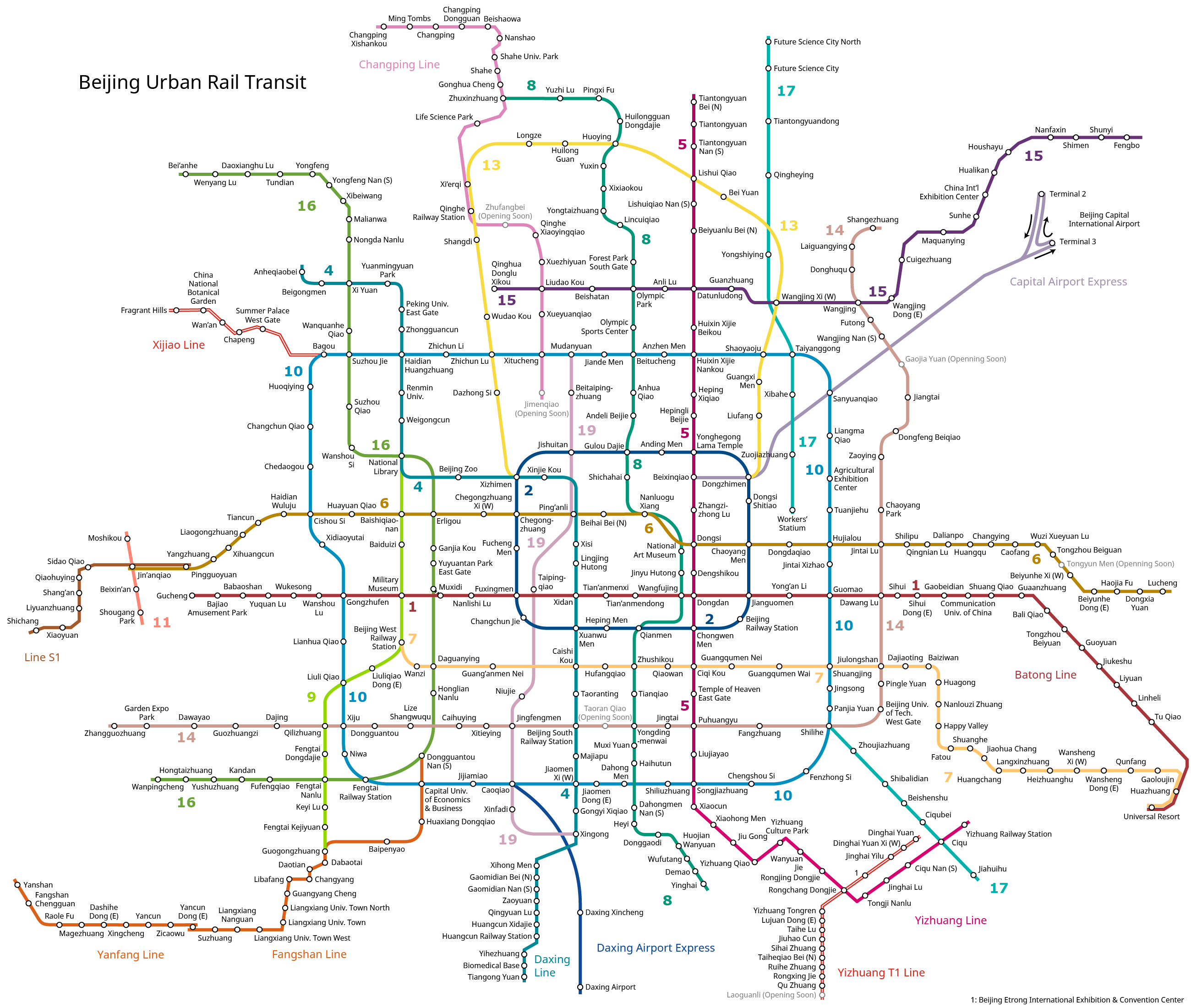

When I first arrived in Beijing, just under two years ago, Line 15 existed, but it didn’t reach our campus. On the map below, Line 15 is the purple line running from the Northeast side of the map below (north of Peking International Airport), and ending just before the western side of the Yellow Line 13 “semi-loop”. When I arrived, Line 15 only ran from the Northeast side of the map to the eastern leg of Line 13, at Wangjing West station.

When I arrived, I heard second hand stories about the subway system from those who would catch a bus to Wudaokou Station on line 13 or Xitucheng Station on Line 10. However, at that time, I was not being very adventurous as far as riding the Beijing bus system, so most of my exploring in those first four months went as far as I could reach on foot.

But even as I arrived, the big tunnel boring machines had finished their job, and the third phase of Line 15 was due to be opened “before the end of the year.” In true Chinese fashion, that meant opening Line 13 on the very last Sunday of 2014, only a few days before solar New Year.

And so it was in the Winter and Spring of 2015 that my rides of the Beijing Subway system began. I had been given a Beijing Metro card when I first arrived, but now I started using it. With colleagues at the College, I would head out on Line 15 from Lioudaoku Station (second from western end), to the transfer to Line 8 at the Olympic Green, then two or five stations to Line 10 or Line 2 … the two loop lines … and then to the “Embassy” district of Sanlitun. And meet up with people to eat Texas BBQ at the Texas BBQ place in Beijing (that is, the Home Plate).

Or … still shy about riding the buses … from my home station on Line 15 to Line 8 at the Olympic Green, then Line 10 at Beitucheng, then six stations west to Hadian-huangzhang, and then walking north from the station to the Electronic Market in Haidian district center.

And this is one common way to use the subway. My line to transfer to transfer to (etc.) to the destination station, which exit, walk which way, hopefully get there. The (automated) announcements in the subway are first in Chinese then in English, with connections clearly announced, so you can work out a route as “15 to 8 to 10 to Tuanjiehu Exit C,” and sketch the route to the destination from there.

Just because the transfers are easy to work out does not mean they necessarily easy to do. While the route of transfers are clearly marked, the Beijing subway system is not particularly shy about expecting people to walk fairly long distances to make transfers. Transfers that are cross platform or up an escalator, across a hall and down another one are the exception, rather than the rule.

Late in my first school year, my wife was able to join me for a month, and in my second year she was able to be in Beijing the whole year. And my wife, among other skills, is a fashion designer and skilled seamstress, and was determined to explore the various markets spread across Beijing. She could not get everywhere she wanted to go via subway alone, so we started to learn how to combined subway and bus transport.

Using the Beijing bus system is much more challenging for someone who does not speak Chinese than using the subway system. Luckily the same metro card works for both, and can be loaded with money in Chinese/English machines in the subway. Variable fare buses work by tapping into the machine at entrance when getting on and tapping into the machine at the exit when getting off. But the bus stop information given at the bus stops requires an ability to read Chinese characters.

Luckily, thanks to the magic of a VPN which allows access to Google Maps, it’s possible to hover over bus stops near a subway station and over bus stops near the final destination and work out which buses go where. And while the bus stops are named in Chinese characters, the buses are numbered in Arabic numerals (thanks Arabia!!), with a bit of time invested into studying the alternatives (with the time required typically extended by the slow pace of the internet when accessing international sites), it is possible to plan a combined route.

The Astonishing Pace of Beijing Subway Expansion

Some of the subway lines that I have used in my two years in Beijing have quite a long history. However, many of the lines I rely upon are less than a decade old.

Some of the subway lines that I have used in my two years in Beijing have quite a long history. However, many of the lines I rely upon are less than a decade old.

The Beijing Subway was started in 1965, but in its first 15 years it only ran in trial operation, with use strictly limited to approved passengers. It was only opened to the general public in 1981. In the 1980’s, most of the current Lines 1 and 2 were completed, and organized as a main East-West line and a loop. Except for an eastern extension of Line 1 finished in the 1990s, that was it, until the dawn of the 21st century.

The in 2001, Beijing won the bid to host the 2008 Olympic Games, and the result was a dramatic increase in investment in the subway system.

In 2002-03, the next two lines were added. Line 13 is the yellow 3/4 loop line which connects to the eastern and western sides of Line 2, and the Batong Line is the red eastern extension to Line 1. , These were added quickly because they are elevated rail lines.

In 2007-08 … just in time for the Olympics … the next wave of underground lines were added. Line 5, opened in 2007, was the first North-South line in the system. Line 5 is an elevated line at its northern end, but heads underground to pass east of the Embassy district of Sanlitun. The northern and eastern parts of the Line 10 were finished, as well as four stations of Line 8: the transfer with Line 10 and the three stations in the Olympic Park.

Also part of the “Olympic Wave” was the Airport Express, the special 25 yuan (~$4) train that runs express from Dongzhimen, connecting to line 2 and 13, through Sanyuanqiao, connecting to Line 10, and then to the Airport Terminals 3 (International) and 2 (domestic).

But the Olympic Wave was just the beginning of the expansion of the Beijing Subway system. Line 4 was opened in 2009-10 starting in the northwest of the city, running past Peking University, through the heart of Haidian District, then swings further east to connect to Line 2 at the southwestern terminus of Line 13, then runs south through Beijing South Railway Station.

Work was already underway on Line 9, connecting to Line 4 at it’s “eastern turn” to continue through Beijing South Railway Station. However, after the Olympics, the world economy kind of threatened to melt down, and the Chinese government adopted a policy of a dramatic increase in infrastructure spending. This included a dramatic speed up in the planned roll out of the Subway rail system.

The first beneficiaries of the increased roll out where peripheral connecting lines, which could be built much more rapidly as elevated rail corridors, and which dramatically increased the reach of the subway system into outer suburban Beijing. One of these was the numbered Line 15, though this did not yet include the underground metro parts that I use on a regular basis. The other four were “named” subway lines: Changping in the Northwest, connecting to line 13, Fangshan in the Southwest, connecting to Line 9 once Line 9 was completed, Daxing in the South, connecting to Line 4, and Yizhuang, connecting to Line 5.

The 2008 wave of underground lines saw the transition from cut-and-cover subways to subway corridors dug by underground boring machines, and the plan seemed to have been to keep them digging once the Olympics was over. The follow-up corridors were, in short, the ultimate in shovel-ready projects, because the shovels were already in motion. Line 6 was opened in 2012 as a downtown East-West line running north of the already overcrowded Line 1. Work continued on Lines 8 and 10, with Line 8 extending north to connect to the Changping line and south to the new Line 6, and 10 completing the South and West sides of the loop.

Work started on Line 14, a 1/2 loop “L” line running north-south east of Line 5 and east-west just north of the southern leg of the Line 10 loop. This is a line being built in pieces, with the extreme south-western side of the corridor opened in 2013-14 as a seven station suburban extender linking to lines 9 and 10 being opened, while the next phase was the main North-South section, extending around the bend to connect to Line 10 and then west to the Beijing South Railway Station, opened in 2014-15.

Line 7 was opened in 2014, connecting with Line 9 at Beijing West Railway Station and running east-west just south of the old city of Beijing, and then extending into the southeast as a suburban extender between the Yizhuang and Batong lines.

And, of course, most importantly of all … from my perspective … the underground section of the first phase of Line 15 was built, running north of the Line 10 loop, connecting (east to west) to lines 14, 13, 5 and 8, running past the campus of my university, and then ending (without a transfer station) just next to the Line 13 corridor, about a half a mile north of the Line 13 Wudaokou Station that we sometimes use.

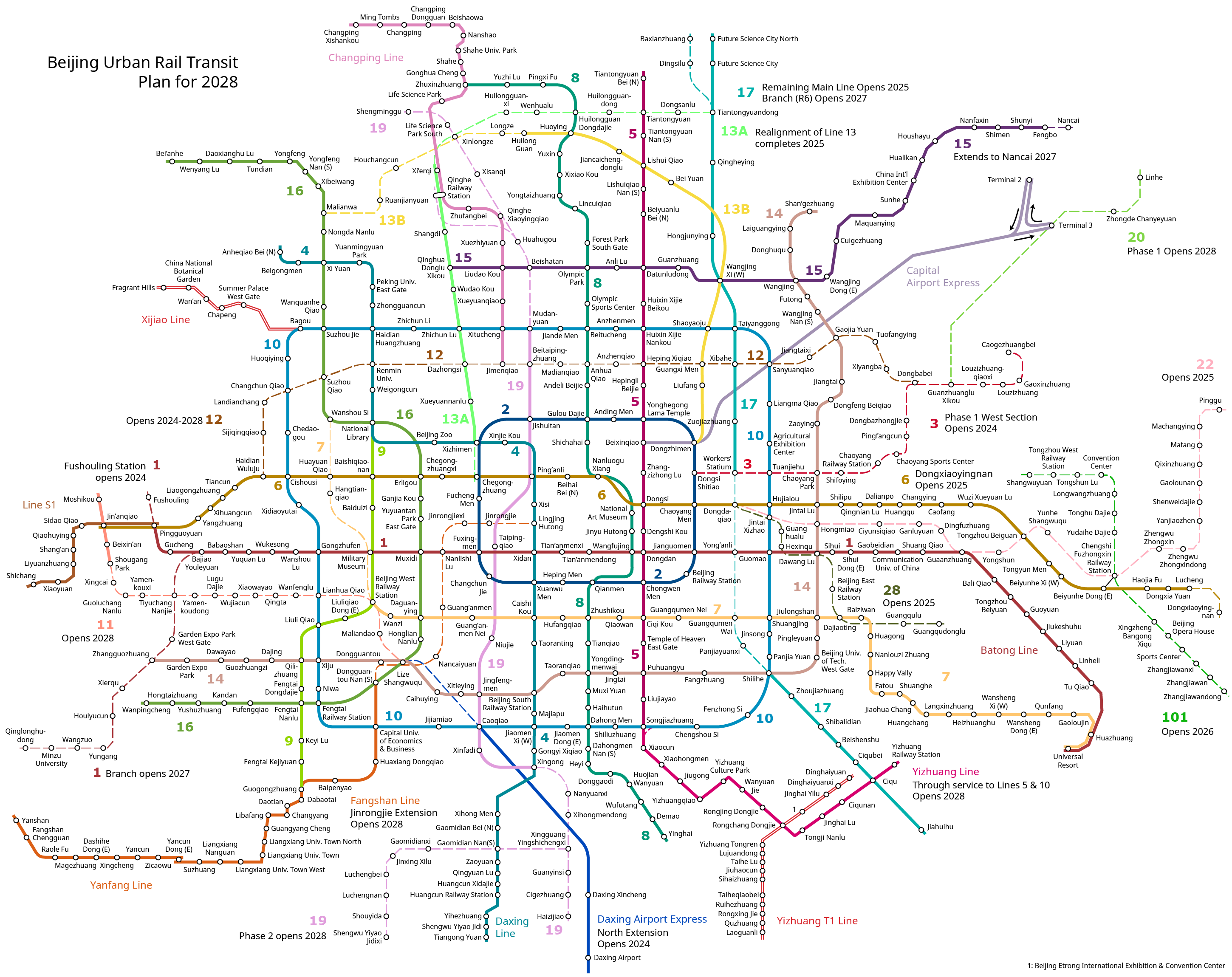

And Beijing Is Just Getting Started

Well, the threatened world economic meltdown is now on the back-burner, at least for the moment, so you might think that it’s time to slow down subway construction.

But even as the post-Panic-of-2008 wave were rolling out, the conditions were being laid for keeping up the pace of subway expansion.

This time, the issue is air pollution. Beijing is a city of 20 million people, and geography and a growing population of cars ensures that Beijing air quality is often quite bad at all times throughout the year. The local saying is “only the wind can clean the Beijing air”, which means that only a strong wind blowing in across the northern hills and mountains from the Mongolian and Siberian plains can give a genuinely low-pollution day.

And Beijing is also a city in which many millions of which depend on district water heating in the winter time … and the largest energy source for that district water heating is still coal. In wintertime, what would be “bad” air days in summer go from bad to worse.

At the same time, the general Chinese turn of the century national policy to promote the automobile industry combined with the relentless growth in Beijing’s working population means that Beijing’s broad avenues and four Ring Road expressways and multiple connecting expressways often become mired in gridlock.

And, I suspect, the Olympic Wave of subway expansion turned the system into something that was a guaranteed driver of property values. I know that in the year and a half after Line 15 opened, two new apartment building projects started just to the east of our campus, in easy walking distance to one of the new subway stations.

And with all of these driving forces, the new 5 year plan came out, and it said, “let there be subways.” You’d probably have to squint if you tried to get the details of the 2021 plan, as announced last year, but you should get the idea from not squinting.

- There are two new east-west lines planned. One is Line 3 running through the old city, playing cross-cross with Line 6. The other is Line 12, running inside of the north side of Line 10 like line 14 will run inside the south leg.

- There are three new north-south lines planned. One is Line 17 running in between the eastern legs of the Line 2 and Line 10 loops, extending north of a planned suburban Science Park and south to intersection with the end of the Yizhuang suburban extender. The other is Line 16, running through the western suburbs of Beijing, first playing criss-cross with the western side of Line 4, then playing criss-cross with Line 9, including a connection to an extension of the suburban Fangshan Line that extends from Line 9.

- There are two additional north-south connections being completed. One is the southern phase of Line 8 through Olympic Park. The Olympic Park is on an North-South axis with the Forbidden City, but Line 8 presently swings east of that axis to end at the National Art Museum. This will be extended to run east of the Forbidden City and Tiananmen Square, and then run south between lines 5 and 4. The second is formed by extending the northern Changping subway extender past lines 15 and 10, to end at the new Line 12, where it will meet the extension of Line 9 coming up from the south.

In any other country in the world, after describing those plans for the coming five years, you’d step back and say, “wow, what an ambitious plan.” In China, you say, “so, that’s the basics, what else are they doing?”

- They are building a new airport, so of course they are building a new airport express, which will connect to the southern side of the Line 10 loop.

- They are also extending the Peking International airport express, to connect to line 5.

- They are finishing Line 14, so the “western” and “eastern” ends will connect.

- They are building a “CBD Line” through the CBD section of East Beijing, between the Lines 6 and 17 transfer station to the north and the Lines 14 and 7 transfer station to the south.

- They are extending Line 7, to connect to the end of the “Batong” extender that runs east of Line 1;

- giving the Fangshan suburban extender in the southwest it’s own extender in the Yanfang line

- building the western Mengtou line as a western extender for Lines 6, 3 and 1;

- building the Western Suburban Line connecting to the northwest corner of the Line 10 loop and running out to the Summer Palace;

- and building Line 22 south of the Peking International Airport, connecting with the eastern end of Line 3 and terminating on Line 14.

A Story of Suburban Extenders

My home subway line, Line 15, is a line which has had a lot of different planned western alignments. When I arrived in China, it was planning to run under Line 13, run through Tsinghua University (the “Harvard of China”), and terminate at Line 4 at the east gate of Peking University (the “Yale of China”). It now seems that, instead, they plan to make the current Line 15 terminus permanent, making a Qinghua East Road Station for Line 13 as a transfer station with Line 15.

Now, once they decided to build that transfer station, they could just do it. That is, I could have seen construction equipment working next to the Line 13 elevated rail corridor before I left Beijing.

But while it could happen, I don’t really expect to see that work start anytime this year.

When we got our Line 15 extension, it opened with transfer stations to Line 8, Line 13, and Line 14. But not Line 5. The word was that work on the transfer connection to Line 5 was not yet complete. That was a major pain the first time my wife and I went to the Pearl Market on Line 5, turning a 1 transfer trip into a 3 transfer trip.

The transfer station had opened by the time my wife started using the international wing of the China-Japan Friendship Hospital for various medical services, and so Line 5 plus a bus connection is how we get to the hospital. One time for tests, we had to be in the hospital before 8am, so we were transferring during rush hour. It was not quite as bad as the video at the top of the blog, but we had to wait for three trains before we were lucky enough to have some people getting out at the door we were waiting at, giving us enough room to squeeze onto the train.

Escaping Beijing rush hour traffic jams, whether in a car or in the crush of a Beijing bus in rush hour, is something that many people are willing to put up with very crowded subway conditions for. That means that even as lines become crowded, there continues to be people moving into apartments to be “convenient to” those subway lines. So the lines that have been in place the longest … lines 1, 2, 13, and 5 … can get very crowded, indeed.

So I would not be surprised if there was not a lot of urgency in providing the Line 15 and Line 5 transfer station, adding even more passengers to a line that was already crowded. Indeed, the Line 5 transfer station was not finished until after the Line 8 extension to Line 6 was finished, providing a new connection from the northern suburbs to the inner cities, and providing some relief to Line 5.

And for similar reasons, I am not expecting rapid work on the Line 15 to Line 13 transfer station. The video at the head of this blog is the transfer station between the Changping suburban extender and Line 13. Many people in that crowd that you see is heading south on Line 13 to places like Tsinghua University, along the Line 13 line, but many are also heading to the Line 10 and Line 2 Transfer stations. But with the Changping extension, many of those people can stay on the Changping line, and transfer to Line 10, or to the new Line 12.

And I am not certain, but I would not be surprised if after the Chongping extension opens, providing some relief to the western side of Line 13 … that is when Line 15 will get the Line 13 transfer station at its western terminus.

Conclusions and Conversations

So, which big American city do you wish was pursuing subway expansion as aggressively as the Municipality of Beijing?

And the rest of the Sunday Train rules also apply ~ any topic on sustainable transport and sustainable energy is always on topic, so if you aim to raise a point that is not directly on the topic of this weeks blog, just drop in a “Energy:” or “Transport:” prefix and raise away.

Recent Comments