(2 p.m. – promoted by ek hornbeck)

I saw this news back in early January (Columbus Ledger-Enquirer 8 Jan 2014):

I saw this news back in early January (Columbus Ledger-Enquirer 8 Jan 2014):

A high speed rail line between Columbus and Atlanta would cost between $1.3-$3.9 billion over the next 20 years to build, but once up and running would more than pay for its operations and maintenance, a consultant said today.

It could also have a huge economic impact, according to Kirsten Berry, project manager consulting firm HNTB Corp., which performed the $350,000 study of the economic feasibility study of high speed rail between Columbus and Atlanta. The study was funded with a $300,000 Georgia Department of Transportation grant and the rest in private donations, according to city Director of Planning Rick Jones.

Now, the actual feasibility study itself has not been released, although the overview presentation to the Columbus GA stakeholders has been released, and I was going to wait until that feasibility study was available to talk about this on the Sunday Train. But then this happened:

Atlanta (CNN) — Empty streets, shuttered storefronts and abandoned vehicles littering the side of the road. That was the scene across much of metropolitan Atlanta on Wednesday as people hunkered down to wait out the aftermath of a snow and ice storm that brought the nation’s ninth-largest metropolitan area to a screeching halt.

… and given the severe state of auto-dependency in the greater Atlanta area, I concluded that the state of plans for HSR in Georgia merits a closer look.

A Tale of Two Columbus HSR corridors and Two Locally-driven Efforts

This feasibility study of a High Speed Rail corridor from Columbus, Georgia to Atlanta is similar to the Columbus, Ohio to Chicago via Northeast Indiana HSR study, in that it has been driven from the ground up rather than the top down:

Mayor Teresa Tomlinson established a Passenger Rail Commission in late 2011 made up of community leaders from the public and private sectors. Attorney Edward Hudson and State Rep. Calvin Smyre are co-chairs of the commission. Money was secured for the consultant’s fee and the first steps were taken to determine the feasibility of the idea. One of the most encouraging things about the consultant’s findings is the projected economic impact on the areas involved in the rail system. The report said that, based on what has happened with similar rail lines in other cities, stakeholders can expect to see 11,000 to 28,000 new jobs per $1 billion invested. Tomlinson said the impact locally would be akin to four Kia plants.

There is also a similarity in that this is an additional spoke being proposed to a set of plans for a hub anchored on a major national metropolitan center. In the Columbus, OH case, all of the Ohio Hub and much of the Midwest Regional Rail System exist as plans on the shelf, but there is active investment in the Rapid Rail Chicago to St. Louis and the Rapid Rail Chicago to Detroit rail corridors. In the Columbus, GA case, all of the Georgia corridors connecting to Atlanta are plans on the shelf, though with ongoing federally-funded ongoing planning activity for the Atlanta to Charlotte HSR corridor, while it is the Washington DC to Charlotte via Richmond HSR corridor that is receiving a variety of active investments.

There is also a similarity in that this is an additional spoke being proposed to a set of plans for a hub anchored on a major national metropolitan center. In the Columbus, OH case, all of the Ohio Hub and much of the Midwest Regional Rail System exist as plans on the shelf, but there is active investment in the Rapid Rail Chicago to St. Louis and the Rapid Rail Chicago to Detroit rail corridors. In the Columbus, GA case, all of the Georgia corridors connecting to Atlanta are plans on the shelf, though with ongoing federally-funded ongoing planning activity for the Atlanta to Charlotte HSR corridor, while it is the Washington DC to Charlotte via Richmond HSR corridor that is receiving a variety of active investments.

Now, for both corridors, there are network benefits to connecting to other, already operating, Rapid Rail and/or bullet train corridors. However, for both corridors, it is clear that the main focus is connecting to a major metropolitan center from smaller centers. Columbus may be the third largest municipality in Georgia, but while the Atlanta urbanized area stands 9th in the list of US urbanized areas, with about 4.5m people, Columbus stands 147th, with about 250,000 in its urbanized area. In that regard, the corridor is more similar to northern Indiana to Chicago leg of the Columbus – Fort Wayne – Chicago proposal than the full Columbus, OH to Chicago, anchored by an urbanized area population of 8.6m on one side and 1.3m on the other.

This makes this feasibility study particularly interesting, since connecting a a city of 250,000 to a major national metropolitan center makes for a more challenging cost-benefit case than connecting a city of 1.3m to a major national metropolitan center. That does not mean, of course, that this analysis applies across the board to any corridor connecting a 4m+ city with a quarter million population city, since terrain and existence of available transport corridors will have a substantial impact on cost, and of course Fort Benning will boost ridership for Columbus Georgia compared to many other similar sized cities, but it remains an interesting indicator for this type of corridor.

And there are, of course, more prospective 250,000+ population anchors for corridors to major national metropolitan centers than there are 1m+ anchors, so this pushes the envelope regarding the scope of High Speed Rail for picking up a substantial part of our intercity transport task.

Rapid Rail versus Bullet Trains between Columbus, GA and Atlanta

This feasibility study looks at three alternative systems:

This feasibility study looks at three alternative systems:

- . The least expensive, and slowest, is a diesel Rapid Rail system with a top speed of 110mph and an average transit speed of 55mph, with four daily round trips of 1:36 to downtown Atlanta. This is laid out on a mix of existing freight rail corridors and existing abandoned rails corridor (shown in green). The capital cost is estimated at $1.3b ($13m/mile). This has a projected operating ratio of 0.83 in 2030 rising to 0.95 in 2050, indicating that it would require an operating subsidy ~ and also that it would not be in the front of the line for FRA funding if there is a Federal HSR funding unlock in 2017/2021.

- The most expensive, and fastest, is an electric bullet train system with a top speed of 150-220mph and an average transit speed of 71mph, with six daily round trips of 1:01 to downtown Atlanta. This is laid out on dedicated dual track on an Interstate Highway alignment. The capital cost is estimated at $3.9b ($43m/mile). This has a projected operating ratio of 1.21 in 2030 rising to 1.50 in 2050, so it would be financially self-sustaining with a 20% to 50% operating surplus available for capital works for service improvements.

- The intermediate option is a diesel high speed rail system with a top speed of 110-150mph and an average transit speed of 63mph, with five daily round trips of 1:26 to downtown Altanta. This is the same corridor as the electric bullet train, except for the electrification, and could be built as the first phase of the electric bullet train system. The capital cost is estimated at $2.0b ($22.2m/mile). This has a projected operating ratio of 1.15 in 2030 to 1.36 in 2050, so it would also be financially self-sustaining. It would have lower operating surpluses, but also substantially lower up front capital subsidy.

Comparing the three corridors, we see that unlike the Columbus OH to Chicago corridor, the Rapid Rail alternative requires an operating subsidy. This is not surprising. Rapid Rail alternatives tend to be time-competitive with driving rather, while bullet trains are much faster than driving. Not only is the total potential ridership for a Rapid Rail system smaller, but the revenue-maximizing ticket price is also lower. For larger transport markets, including Central Ohio and Northeastern Indiana to Chicago, there is still an operating surplus available even though the Rapid Rail is serving a smaller slice of the total transport market. However, as the size of the total intercity transport market declines, a larger slice of the total market is required for a rail corridor to hit an operating surplus.

Note that the corridors as shown on the map end at Atlanta’s airport, but the study corridors continue the route through to the expected but not yet under construction Atlanta Multi-Modal passenger terminal in the “Gulch” region of downtown Atlanta. This is partly accounts for the relatively low average transit speed, even for the bullet train system, since the transit from the airport to downtown Atlanta would be a regular express urban rail corridor in all three cases. It also means that the transit speed comparison to driving is better than it might at first appear, since (at least when there is not two inches of snow on the ground) interstate highway speed from Columbus GA to the outskirts of Atlanta may be fairly high, average driving speeds tend to slow down substantially for motorists driving into downtown Atlanta.

The presentation materials do not provide estimated cost-benefit impacts, A quarter or more of the $700m difference in capital subsidy between the diesel Rapid Rail and the diesel High Speed Rail is accounted for by the operating surpluses available from the diesel high speed rail versus the operating subsidies required by the diesel Rapid Rail service, though that still leaves the net subsidy about 1/3 higher for the diesel High Speed Rail version for about 1/4 more riders, so its possible that the cost-benefit analysis in the feasibility study will favor the subsidized Rapid Rail service.

On the other hand, a cost-benefit analysis performed under status-quo assumptions can also be expected to understate the prospective benefit of the corridor, since all three options will result in fewer net CO2 emissions due to traffic diverted from motor vehicle and air travel, and actual marginal cost of CO2 emissions required to keep 80% of current reserves in the ground is likely to be substantially higher than the $28/ton that has been the standard used in cost-benefit analyses. At the same time, the standard analysis will omit uncounted self-insurance benefits to having a greater variety of transport options, and the benefits when a corridor is used as an emergency transport alternative tend to scale with the capacity of the system.

Integrating the Columbus/Atlanta Corridor into an Amtrak Crescent

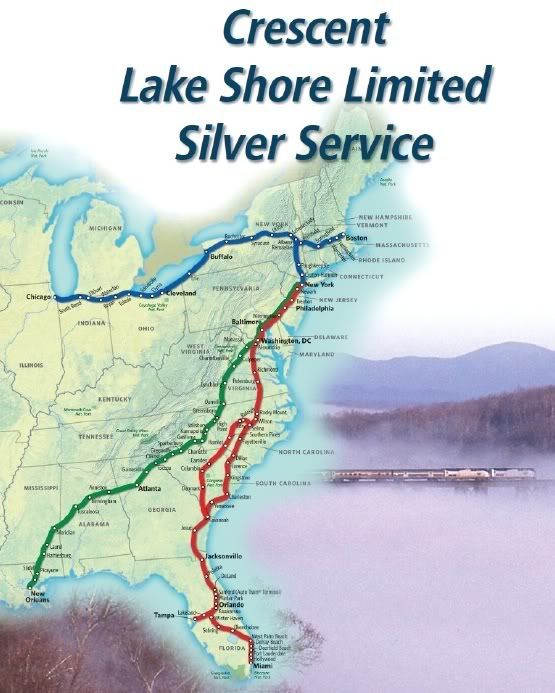

There is at present a single intercity rail service through Atlanta, the Amtrak Crescent, which runs from New York City to New Orleans. Given the speed limitations of operating on conventional freight rail corridors for most of its length, this is a quite well timed service for sleeper service to Washington DC and NYC, with the westbound service leaving DC at 6:30pm and arriving in Atlanta at 8:13am, and the eastbound service leaving Atlanta at 8:04pm and arriving in DC at 9:53am.

There is at present a single intercity rail service through Atlanta, the Amtrak Crescent, which runs from New York City to New Orleans. Given the speed limitations of operating on conventional freight rail corridors for most of its length, this is a quite well timed service for sleeper service to Washington DC and NYC, with the westbound service leaving DC at 6:30pm and arriving in Atlanta at 8:13am, and the eastbound service leaving Atlanta at 8:04pm and arriving in DC at 9:53am.

Indeed, as the required “PRIIA” Analysis of the Crescent route reveals:

At present, with 52% percent of passengers traveling only on the northern segment and 23% of passengers traveling through Atlanta, the Crescent is capacity-constrained on the 18hr Atlanta-NYC side of its trip, limiting opportunities to earn additional revenue. However, it generally has surplus capacity on the 12hr Atlanta / New Orleans side of its route, with only 21% of passengers traveling exclusively within the southern segment.

The solution that Amtrak proposed for this is to split the train at Atlanta, taking cars off from the westbound service that would skip the round trip Atlanta/New Orleans and connect onto the next eastbound service. Those seats are excess capacity on the Atlanta to New Orleans segment and scarce capacity on the Atlanta to DC/New York segment, and so would allow an increase in revenues and reduction in subsidy per passenger mile. Part of the additional revenue would be due to the ability to add additional connecting Amtrak buses at Atlanta, where the demand to use the service exists, but that demand is primarily focused on the north/eastern leg of the Crescent route.

However, the current Amtrak Atlanta station is not suited to supporting this division of the Amtrak Crescent service, and so this is a service improvement that is hanging on either an investment in the facilities at that station or, preferably, establishment of a multi-modal passenger terminal suitable for use as a through-station for the Amtrak Crescent.

However, with nearly twelve hours between the westbound and eastbound Crescent services, a Columbus-Atlanta HSR corridor offers an opportunity for an even more effective service upgrade, with the cars taken off of the westbound Crescent continuing on to Columbus GA and terminating there in the morning, and then leaving for Atlanta in the evening to continue on to DC and NYC as part of the Crescent service. Between those two services, would be the opportunity for at least one additional round trip between Columbus and Atlanta, which could be integrated into the dedicated Columbus-Atlanta schedule to better fit daily demand peaks. This would upgrade the five round trips per day of the diesel HSR corridor to seven trips per day, including the continuing Crescent trips and an additional round trip by the cars of the Crescent train.

Integrating the Columbus/Atlanta Corridor into an Atlanta Hub

As the largest urbanized population in its region of the country, it is no surprise that Atlanta provides the focus of HSR planning in Georgia. And, as already mentioned, the Columbus GA — Atlanta corridor is by no means the first HSR planning exercise involving Atlanta.

As the largest urbanized population in its region of the country, it is no surprise that Atlanta provides the focus of HSR planning in Georgia. And, as already mentioned, the Columbus GA — Atlanta corridor is by no means the first HSR planning exercise involving Atlanta.

The Southeast HSR corridor has been a designated HSR corridor under the federally designated corridor system for quite some time now. It follows the rough alignment of the Crescent route, but in its current version it runs through Richmond, Virginia through to Raleigh, North Carolina, along the NYC/Florida alignments, where it becomes a triangular corridor, splitting into a Greensboro / Charlotte / Atlanta leg and a Columbia SC / Savanna / Jacksonville leg, with Jacksonville / Macon / Atlanta forming the third side of the triangle.

However, while the first phase of planning for Charlotte / Atlanta was completed in 2008 (pdf), Georgia has since extended that planning to examine Atlanta / Birmingham, Atlanta / Macon / Jacksonville, and Atlanta / Chattanooga / Nashville / Louisville (pdf). So when we include both the Atlanta / Charlotte corridor (which is notionally the next extension once the DC / Richmond / Charlotte section of the Southeast HSR corridor is finished) and the present Columbus GA / Atlanta corridor, that would make the proposed Atlanta multi-modal passenger terminal the hub for a system of five spokes extending to Nashville, Charlotte, Jacksonville, Columbus GA, and Birmingham.

In short, if there is indeed a “Great HSR policy unlock” in 2017, Atlanta could offer one of the primary focuses of attention that policy over the coming decade.

What I want to look at here is where a Columbus GA to Atlanta corridor would stand in that mix. As the cost-benefit analysis has not been published, I will make the comparison based on expected operating ratios (revenues divided by operating and maintenance costs, where a value bigger than one implies an operating surplus). Since most of these analyses include a range of assumptions, from conservative through intermediate to optimistic, I will take the intermediate estimate. This is the diesel HSR option in all cases (where Atlanta/Charlotte considered both 125mph and 150mph diesel HSR alternatives), so neither the least nor most expensive alternative. Ranking them in order (initial operating ratio weighting more heavily due to discounting):

- Atlanta / Birmingham ($5.5b capital cost) ~ 1.85 initial operating ratio, rising to 2.13

- Atlanta / Chattanooga / Nashville / Louisville ($16.4b capital cost) ~ 1.66 initial operating ratio, rising to 2.22

- Atlanta / Macon / Jacksonville ($8.9b capital cost) ~ 1.66 initial operating ratio, rising to 2.18

- Atlanta / Columbus GA ($3.9b capital cost) ~ 1.15 initial operating ratio, rising to 1.36

- Atlanta / Charlotte ($2b-$2.5b capital cost) ~ 0.68-0.72 initial operating ratio, rising to 1.25-1.3 (break-even in 15-16yrs)

The Atlanta / Louisville study includes consideration of truncating the corridor at Chattanooga and at Nashville (p. 4-163), where the truncations have intermediate operating ratios rising to 1.97 for the Chattanooga truncation and 2.09 for the Nashville truncation, and with cost-benefit of the full corridor greater than either truncation. While the truncated corridors merit consideration if the capital cost of the full corridor is beyond reach, the full corridor appears to be superior to either truncated version. In essence, the full corridor leverages the relatively high costs of the Atlanta / Chattanooga and Chattanooga / Nashville legs with a substantially lower cost leg from Nashville to Louisville.

It is notable that for the Atlanta/Charlotte corridor, neither the Rapid Rail alternatives nor the fastest electric bullet train alternatives are projected to generate appreciable operating surpluses, with the rapid rail alternatives coming close to break-even at the end of the 30yr projection and the electric HSR 220mph bullet train having the consistently worst performance. Under the status quo conditions of the projection, the extra maintenance costs of both track and electrification infrastructure are not compensated for by the lower energy running costs of the trains.

The Long Planning Horizons of US HSR

To me, one of the most striking features of the January presentation is the timeline it presents. Year 1 through 10 are the preliminary feasibility analysis, and the tier I and II NEPA (National Environmental Policy Act of 1969) process, with each including a Draft Environmental Impact analysis, a Final Environmental Impact analysis, and a Record of Decision which reflects whether the project passed environmental review. Note that any shortage of funding to proceed with Tier 1 or Tier 2 NEPA analysis would delay this timeline. Then Years 10-18 are occupied with the preliminary design of the corridor, the final design of the corridor, and the acquisition of the right of way. And then finally in the last two years you build the thing. So that is 18 years of analysis, design and ROW acquisition before breaking ground.

To me, one of the most striking features of the January presentation is the timeline it presents. Year 1 through 10 are the preliminary feasibility analysis, and the tier I and II NEPA (National Environmental Policy Act of 1969) process, with each including a Draft Environmental Impact analysis, a Final Environmental Impact analysis, and a Record of Decision which reflects whether the project passed environmental review. Note that any shortage of funding to proceed with Tier 1 or Tier 2 NEPA analysis would delay this timeline. Then Years 10-18 are occupied with the preliminary design of the corridor, the final design of the corridor, and the acquisition of the right of way. And then finally in the last two years you build the thing. So that is 18 years of analysis, design and ROW acquisition before breaking ground.

Under the current policy regime, this highlights the importance of getting Environmental Impact analyses and preliminary design work done for as many corridors as possible, since these phases of the project are dramatically cheaper than the ROW acquisition and construction of the corridor.

It also highlights that if we are going to include HSR to support intercity transport as part of a Pedal to the Metal climate change policy package, we will want to find ways to streamline this process. Of course, we must at the same time take care to avoid throwing the baby out with the bathwater in the sense of sacrificing the protections built into the process, but where the project is to be largely built in existing transport corridors, whether rail or highway right of way, there may be opportunities for substantial streamlining through approval of a design envelope so that the focus of the NEPA review process is kept on uncovering and avoiding or mitigating substantial ecological environmental impacts.

A key element of all of this is a secure federal funding base for intercity Rapid Rail and High Speed Rail, where the prospect of winning that funding will encourage state governments and coalitions of local communities to push plans through the planning pipeline. Beyond that, in a true Pedal to the Metal policy approach, we could also gain substantial accelerating of the timeline by advancing parallel alignments through design and NEPA clearance, recognizing that the moderately higher cost for designing more alternatives than we are going to build can be offset by substantially trimming the opportunity cost of waiting 18 years from the start of the planning process until we are ready to break ground.

It seems highly likely that if we shifted from a status-quo-biased benefit-cost analysis to one which took the existential threat of the climate crisis to the continued survival of the United States into account, this proposed Columbus GA to Atlanta HSR corridor would be one of many that would fully merit funding … and looking for some way to get it built before 2035.

Conclusions and Considerations

So now, as always, rather looking for some overarching conclusion, I now open the floor to the comments of those reading. What High Speed Rail corridor would you most like to see build? Especially, what High Speed Rail corridor from a 250,000 / 500,000 urbanized area to a major national metropolitan center would you like to see built?

If you have an issue on some other area of sustainable transport or sustainable energy production, please feel free to start a new main comment. To avoid confusing me, given my tendency to filter comments through the topic of this week’s Sunday Train, feel free to use the shorthand “NT:” in the subject line when introducing this kind of new topic.

And if you have a topic in sustainable transport or energy that you want me to take a look at in the coming month, be sure to include that as well.

3 comments

Author

… but the Crescent connects in New Orleans with the Sunset Ltd from LA …

Back in the late 60’s when I was living in Europe, I took the Orient Express from Paris to Istanbul. I still have my compartment key.

Canadian singer, Loreena McKinnett wrote the song “Dante’s Prayer” while traveling across Siberia. Her opening comment is quite a contrast to the NBC piece. Makes me curious.