Starting in 1903, Race 1, an earlier variant of today’s pathogen, ravaged the export plantations of Latin America and the Caribbean. Within 50 years, Race 1 drove the world’s only export banana species, the Gros Michel, to virtual extinction. That’s why 99% of the bananas eaten in the developed world today are a cultivar called the Cavendish, the only export-suitable banana that could take on Race 1 and live to tell.

Over the half-century it took to wipe out the Gros Michel, Race 1 caused at least $2.3 billion in damage (around $18.2 billion in today’s terms.) And that was in the commercial heart of global banana production. Tropical Race 4, by comparison, has damaged $400 million in banana crops in the Philippines alone.

But the bigger difference now is that, compared its 20th-century cousin, Tropical Race 4 is a pure killing machine—and not just for Cavendishes. Scores of other species that are immune to Race 1 have no defenses against the new pathogen. In fact, Tropical Race 4 is capable of killing at least 80%—though possibly as much as 85%—of the 145 million tonnes (160 million tons) of bananas and plantains produced each year, says Ploetz.

And at $8.9 billion, bananas grown for export are only a fraction of the $44.1 billion in annual banana and plantain production—in fact, bananas are the fourth-most valuable global crop after rice, wheat, and milk. Where are the rest of those bananas sold? Nearly nine-tenths of the world’s bananas are eaten in poor countries, where at least 400 million people rely on them for 15-27% of their daily calories. And that’s the really scary part. Since the first Panama disease outbreak, bananas have evolved from snacks into vital sustenance. And this time there’s no back-up banana variety to feed the world with instead.

…

In the same way that the Cavendish gets all the fame, brand names like Chiquita and Dole dominate the popular conception of the banana market. But exports make up only 15% of global output; the rest is consumed by banana-producing nations or sold unofficially in regional markets. In fact, the top two banana and plantain producers—India and China—don’t export at all, though they produce a combined 35% of the global yield.

The developed world prizes bananas as a food of convenience—it’s cheap, portable and reasonably healthy. In poor countries, however, bananas are often a basic source of nourishment for at least 400 million people. The average person in Uganda, Gabon, Ghana and Rwanda relies on bananas and plantains for more than 300 calories each day—around 16% of the UN’s nourishment threshold (and bear in mind that around 20% of the 74 million people living in those four countries are undernourished). Roughly 70% of all bananas consumed locally are vulnerable to Tropical Race 4.

And while millions of farmers feed their families with home-grown bananas, many millions more use income from growing them to buy other crops. Bananas are the most important export commodity for Ecuador, Panama, Costa Rica, and Belize. They’re in the top three in Colombia, the Philippines, Guatemala, Honduras, and Cameroon. That’s a lot of the developing-world economy reliant on a very vulnerable crop. “This disease is a problem, not only because of its potential impact on the price and availability of our favorite fruit, but also because it’s a life-changing event for the people in developing countries who rely on bananas as a staple food and incomes,” Alice Churchill, a scientist studying plant biology at Cornell University, told the Cornell Sun, ”Those affected by [Panama disease] lose both their livelihoods and an important source of nutrition.”

…

The knitting of our fate with that of Tropical Race 4 began more than a century ago, with a banana far tastier than any most Quartz readers have ever had. While its famously creamy flavor made the Gros Michel—or “Big Mike”—a big hit around the Caribbean among small-time farmers, its tough, thick skin and its high yield are what landed this cultivar in cereal bowls and lunch bags far beyond the tropics.

Like all domesticated bananas, the vast majority of Gros Michel didn’t carry seeds. So how did they reproduce? You simply would cut off a chunk of a banana tree, plant it, and wait for your banana tree to sprout. In other words, the bananas eaten commercially are all clones.

Those qualities also gave rise of the industrialization of banana-growing, as they allowed scrappy American entrepreneurs to construct banana empires throughout Latin American rainforests, often building railroads to ports in exchange for long-term land rights. These banana barons pioneered the industrial agriculture model familiar today, maximizing land, minimizing labor, and vertically integrating in order to send their product far and wide.

That let them sell Big Mikes for cheap—an important development given that in 1899, the fruit was still found mainly in posh hotels, where it often was accompanied with instructions on how to peel it. That next year, Americans ate around 15 million bunches of bananas. Within a decade that had surged to 40 million, making them more popular than apples and oranges, as Dan Koeppel documents in his book, Banana: The Fate of the Fruit That Changed the World. At a time when apples and oranges were prohibitively expensive to most Americans, the banana was marketed for mass consumption. United Fruit successfully styled it as the fruit of the common man, its popularity reflected in the slapstick ubiquity of slipping on banana peels found in the films of Buster Keaton, Charlie Chaplin, and other comedians, as Koeppel points out.

From there, United Fruit ramped up marketing to further the banana’s American conquest, hiring doctors to endorse mashed bananas as baby food and setting up a “home economics department” to get images of bananas in front of housewives and in textbooks. After its test kitchens struck upon the idea of the banana as the perfect breakfast on the go, the company began offering coupons on cereal boxes, linking bananas and breakfast cereal for the first time, writes Koeppel.

To ramp up production while preserving its margins, United Fruit began burnishing its famously bloody reputation for union-busting. (A 1928 crackdown on striking United Fruit workers in Colombia inspired the massacre in Gabriel García Márquez’s novel, One Hundred Years of Solitude). The strategic importance of the crop meant that the troops of both Latin American dictatorships—the namesake of “banana republics”—and the US government often enforced United Fruit’s will on unruly workers.

However, in 1903, United Fruit encountered an enemy that all the military interventions in the world couldn’t stop. It first showed up in Panama—a blight that wilted leaves and infected fruits until the entire plant toppled over and died, usually before it could bear any fruit. Once it appeared, it laid waste to a region’s plantations, usually at a gradual pace, but sometimes with devastating speed. It needed only five years to wipe out all of Suriname’s banana plantations.

As you undoubtedly guessed, the pestilence in question is none other than Panama disease, Race 1. As whole plantations failed, United Fruit and others made the obvious choice: they picked up and moved somewhere else in Latin America.

But the blight followed. After it wiped out plantations in Costa Rica, Panama disease followed United Fruit to Guatemala. And then to Nicaragua, then Colombia and then Ecuador. By 1960, 77 years after it had appeared, Panama disease had wiped the Gros Michel out of every export plantation on the face of the planet.

In the Gros Michel’s rise and fall, the banana industry struggled with the paradox that plagues all industrial agriculture crops. Natural reproduction is bad for short-term profits. The way to grow a consistent product at yields that achieve economies of scale is to stamp out the risks of diversity and imperfection that happens when genes reshuffle. To boost profit, you then grow that crop to the exclusion of less valuable species.

This is what’s called a “monoculture” or “monocrop,” the cultivation of a single plant species, usually on a massive, standardized scale. These things come at a cost, though. Just as their genetic similarity makes for cheap, large-scale production, it also prevents monocrops from adapting to attack from pests or disease. (Other disastrous consequences of monocrops include that farmers soak their crops in ever-increasing amounts of harmful chemicals and that this scale of growing is incredibly taxing on the environment.)

No episode in history illustrates this cost more nightmarishly than the Irish potato blight, “the biggest experiment in monoculture ever attempted and surely the most convincing proof of its folly,” as journalist Michael Pollan called it in his book Botany of Desire.

Introduced to Ireland two centuries earlier, the potato had by the early 1800s become a staple crop for farmers, a principal source of food for the poor and a major fodder crop for livestock. The vast majority of Irish farmers were planting a single potato species, the Irish Lumper, to the exclusion of other potato types. When a Mexican fungus-like microorganism hit Ireland, it encountered virtually no natural resistance, destroying around three-quarters of Ireland’s 1846 potato harvest. The blight eventually wiped out one million people between 1845 and 1852. As much as one-quarter of Ireland’s population either fled or died.

Pollan makes an unnerving point about this tragedy. Many of the one million who died “probably owed their existence to the potato in the first place.” In other words, Ireland’s large-scale potato monoculture supported a bigger population than growing a more diverse range of crops would have; when that extra food disappeared, so did they.

Panama disease’s scorched earth campaign was briefly terrible for United Fruit and for many Latin American economies. It was frustrating enough for US consumers to have inspired the song “Yes, We Have No Bananas.” But a tropical reprise of the Irish potato famine it wasn’t.

There are many reasons for this, but a big one is simply that Lumper potatoes were an Irish staple; poor banana farmers in Latin America largely didn’t eat Gros Michel bananas—they were an export good, a nice-to-have snack in wealthy countries. When it came to feeding themselves, farmers in Latin America and the Caribbean had plenty of alternative bananas—species too thin-skinned to be exported or too weird-looking for Westerners to buy. Since Panama disease—remember, this is Race 1 we’re talking about—killed only the Gros Michel and a couple other types of bananas, plantains, as the type of banana commonly consumed in Latin America and Africa are known, were unscathed.

Plus, there was a huge yellow life raft in the form of the Race 1-resistant Cavendish, which Standard Fruit started rolling out in 1947. The rest of Big Banana eventually followed suit, ramping up plantations to produce more sterile Cavendish clones than ever. Soon it wasn’t just the multinationals; because Cavendish plants are so productive, farmers growing subsistence crops for local consumption took to growing them as well. Now around 60% of the 40 million tonnes of Cavendishes grown each year is eaten locally, not exported.

While United Fruit and Standard Fruit—which soon morphed into Chiquita and Dole, respectively—and other banana giants built booming businesses around Cavendish clones, Panama disease was busy too. The banana industry then did the fungus a huge favor: In the 1980s it launched huge Cavendish plantations in Malaysia, one of the ancient cradles of banana civilization. That’s where University of Florida’s Ploetz thinks Panama disease originally came from.

Even though it’s famed as the scourge of Latin America, the fungus is actually the natural foe of Malaysian wild bananas. That’s why moving banana production to Asia was such a bad move; wherever you find the most highly adapted wild bananas, you’re likely to find the most highly adapted diseases. For many millennia, an evolutionary bloodsport between Panama disease and wild bananas has raged on in Malaysian jungles. While the fungus made sure wild bananas passed on only the best genes for survival, wild bananas kept the fungus primed for lethal combat. When the fungus was brought to Latin America in the late 19th century, the Gros Michel never stood a chance. This, after all, was a fungus born to kill the most evolved banana species out there. Wiping out a sterile mutant with no natural resistance was a cakewalk.

The Cavendish was clearly made of tougher stuff. But that helped it only against Race 1, the strain of Panama disease that had been transplanted to Latin America more than a century ago. In the intervening years, the pathogen that stayed in Malaysia kept adapting and out-adapting Malaysian wild bananas. And that’s why Tropical Race 4 is so much more lethal: It’s a fungus with 100 extra years of banana-killing evolution under its belt.

Big Banana’s global conquest didn’t create Tropical Race 4. But it did help “select” it, says Ploetz. By building its business on a monoculture, the big exporters made their species sitting ducks for constantly adapting strains of Panama disease. And by moving banana production around the globe, far beyond the species’ natural habitats, companies ensured that species became host for a vicious disease against which the vast majority of cultivated bananas had no defenses. The good news, relatively speaking, was that in the last 20 years it’s been confined to Asia and Australia. But its sudden appearance in Mozambique and Jordan last year puts it closer to devastating global banana and plantain production—in a way the world has never before seen.

All this might seem alarmist, particularly given how slowly Panama disease typically spreads. Big Banana, for one, would agree with that. “This is something that this industry has dealt with for decades,” said Chiquita’s Ed Lloyd. ”It’s not a ‘sky is falling’ sort of situation.”

To some extent, University of Florida’s Ploetz agrees. “Bananas aren’t going to go extinct—they’re not going to disappear,” he says. “What [Dole and Chiquita] have in their favor is that it’s not going to move through their plantation like wildfire… But the problem is its cryptic nature: Once you have it you don’t know how widespread it is.”

The picture’s much different when you look beyond exported bananas. Tropical Race 4 doesn’t have to spread that fast to start shrinking the food supply for the 400 million people in Asia, Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean who depend on bananas for basic sustenance. The fact that it’s now in Africa is distressing considering that 227 million people — many of them small-scale farmers—are already underfed.

And while Chiquita and other big banana multinationals shrug off its threat to Latin America, it doesn’t sound like they’re taking into account the possibilities that Ploetz flags, such as the Latin American farmers setting up plantations in the affected Mozambique area. Did they scrub their shoes well enough? Time will tell.

Though the banana panic won’t hit tomorrow, the nature of Tropical Race 4 and the fact that scientists haven’t yet found a viable back-up banana to sub in for the Cavendish means an eventual production collapse is inevitable.

What might that look like? In the crude terms that Pollan invoked with the Irish potato famine, the population that owes much of its survival to cheap, productive banana plants is the one that will shoulder the impact when those plants die. If the same huge numbers of the banana-eating global population are going to stay fed, the only viable solution at the moment may be genetic modification. On that front, there are promising signs, though still nothing to take to the bank. While some find the genetically modified alternative objectionable, it’s hard to argue against modifying an already pretty heavily genetically tweaked fruit given the scale of malnourishment or perhaps even starvation, if that’s what it comes down to.

But the GMO lightning rod distracts from the larger cautionary tale: Our reliance on monoculture to feed surging global populations is catching up with us. International agricultural organizations are already scrambling to find new scourge-resistant substitutes for things like rice and potatoes. In fact, so dire are other global agricultural problems that Tropical Race 4’s onslaught doesn’t even get bananas near the top of priority list. ”Getting support to develop new resistant bananas is really tough—there are already so many demands on the international agricultural community,” says Ploetz. “There’s a lot of hunger in the world and bananas just have to get in line behind all those other big problems.

But that’s just a decades old problem that isn’t getting any better, you know, like Global Warming. How about Some More News?

I think Cody’s Showdy is just as important as John Oliver and Sam Bee, and for the same reason. By tackling just a single story per week (for the most part), he’s able to bring a depth of detail that Trevor and Stephen and Seth can’t match.

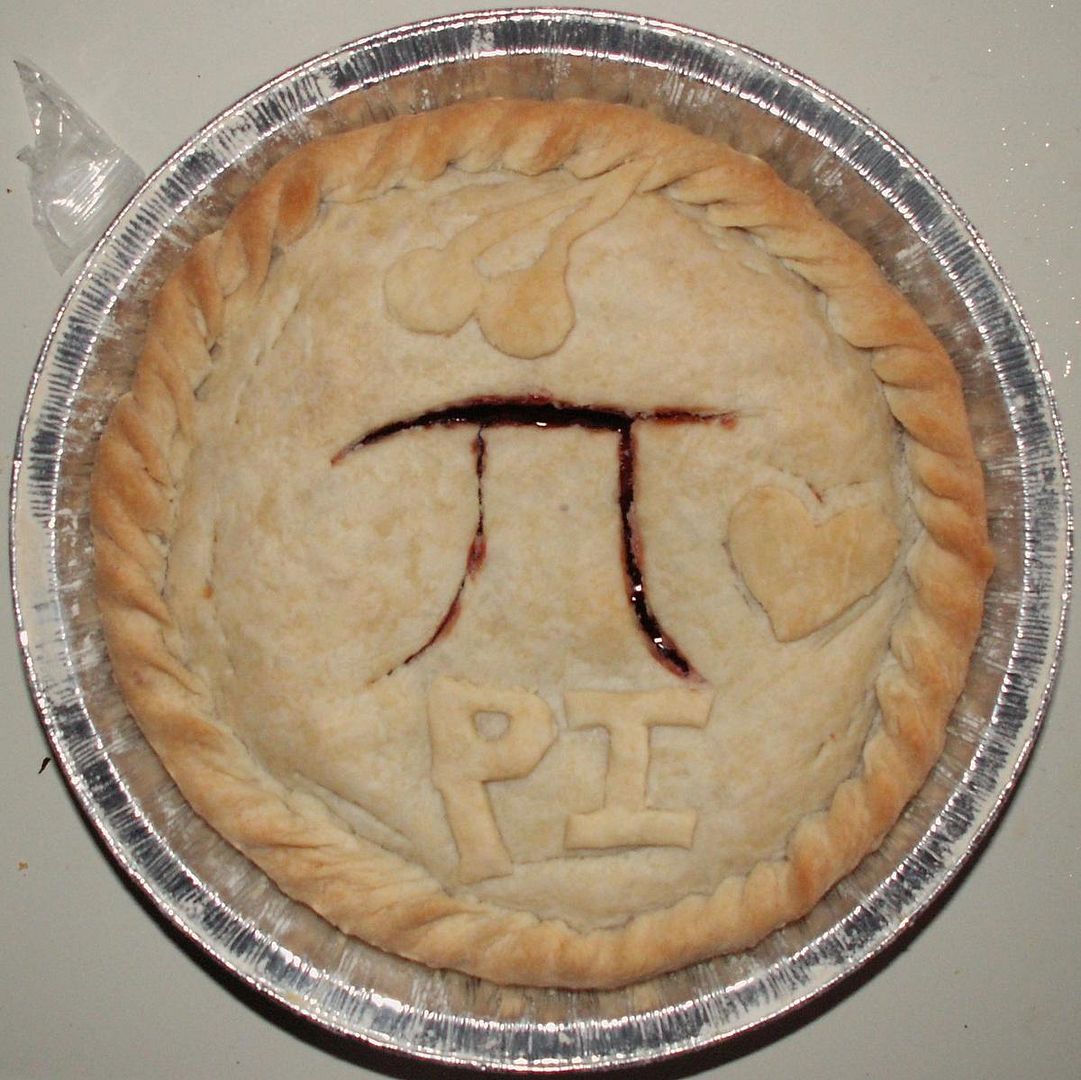

It’s earliest known celebration was in California where in 1988 at the San Francisco Exploratorium physicist Larry Shaw along with the staff and the public marched around one of its circular spaces eating fruit pies. In 2009. The US House of Representatives passed a non-binding resolution declaring 3.14 π (Pi) Day. And in 2010, a French computer scientist claimed to have calculated pi to almost 2.7 trillion digits. This year is no different. The

It’s earliest known celebration was in California where in 1988 at the San Francisco Exploratorium physicist Larry Shaw along with the staff and the public marched around one of its circular spaces eating fruit pies. In 2009. The US House of Representatives passed a non-binding resolution declaring 3.14 π (Pi) Day. And in 2010, a French computer scientist claimed to have calculated pi to almost 2.7 trillion digits. This year is no different. The

Recent Comments