This is your morning Open Thread. Pour your favorite beverage and review the past and comment on the future.

Find the past “On This Day in History” here.

March 13 is the 72nd day of the year (73rd in leap years) in the Gregorian calendar. There are 293 days remaining until the end of the year.

On this day in 1881. Czar Alexander II, the ruler of Russia since 1855, is killed in the streets of St. Petersburg by a bomb thrown by a member of the revolutionary “People’s Will” group. The People’s Will, organized in 1879, employed terrorism and assassination in their attempt to overthrow Russia’s czarist autocracy. They murdered officials and made several attempts on the czar’s life before finally assassinating him on March 13, 1881.

Alexander II succeeded to the throne upon the death of his father in 1855. The first year of his reign was devoted to the prosecution of the Crimean War and, after the fall of Sevastopol, to negotiations for peace, led by his trusted counsellor Prince Gorchakov. The country had been exhausted and humiliated by the war. Bribe-taking, theft and corruption were everywhere. Encouraged by public opinion he began a period of radical reforms, including an attempt to not to depend on a landed aristocracy controlling the poor, a move to developing Russia’s natural resources and to thoroughly reform all branches of the administration.

In spite of his obstinacy in playing the Russian autocrat, Alexander II acted willfully for several years, somewhat like a constitutional sovereign of the continental type. Soon after the conclusion of peace, important changes were made in legislation concerning industry and commerce, and the new freedom thus afforded produced a large number of limited liability companies. Plans were formed for building a great network of railways-partly for the purpose of developing the natural resources of the country, and partly for the purpose of increasing its power for defence and attack.

The existence of serfdom was tackled boldly, taking advantage of a petition presented by the Polish landed proprietors of the Lithuanian provinces and, hoping that their relations with the serfs might be regulated in a more satisfactory way (meaning in a way more satisfactory for the proprietors), he authorised the formation of committees “for ameliorating the condition of the peasants”, and laid down the principles on which the amelioration was to be effected.

This step was followed by one still more significant. Without consulting his ordinary advisers, Alexander ordered the Minister of the Interior to send a circular to the provincial governors of European Russia, containing a copy of the instructions forwarded to the governor-general of Lithuania, praising the supposed generous, patriotic intentions of the Lithuanian landed proprietors, and suggesting that perhaps the landed proprietors of other provinces might express a similar desire. The hint was taken: in all provinces where serfdom existed, emancipation committees were formed.

But the emancipation was not merely a humanitarian question capable of being solved instantaneously by imperial ukase. It contained very complicated problems, deeply affecting the economic, social and political future of the nation.

Alexander had to choose between the different measures recommended to him. Should the serfs become agricultural labourers dependent economically and administratively on the landlords, or should they be transformed into a class of independent communal proprietors?

The emperor gave his support to the latter project, and the Russian peasantry became one of the last groups of peasants in Europe to shake off serfdom.

The architects of the emancipation manifesto were Alexander’s brother Konstantin, Yakov Rostovtsev, and Nikolay Milyutin.

On 3 March 1861, 6 years after his accession, the emancipation law was signed and published.

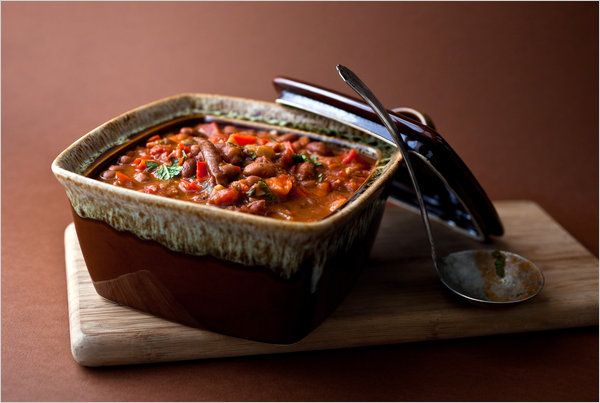

Welcome to the Stars Hollow Health and Fitness weekly diary. It will publish on Saturday afternoon and be open for discussion about health related issues including diet, exercise, health and health care issues, as well as, tips on what you can do when there is a medical emergency. Also an opportunity to share and exchange your favorite healthy recipes.

Welcome to the Stars Hollow Health and Fitness weekly diary. It will publish on Saturday afternoon and be open for discussion about health related issues including diet, exercise, health and health care issues, as well as, tips on what you can do when there is a medical emergency. Also an opportunity to share and exchange your favorite healthy recipes.

On this day in 1947,

On this day in 1947,

Recent Comments