This is your morning Open Thread. Pour your favorite beverage and review the past and comment on the future.

Find the past “On This Day in History” here.

Click on images to enlarge

April 30 is the 120th day of the year (121st in leap years) in the Gregorian calendar. There are 245 days remaining until the end of the year.

On this day in 1900, Jones dies in a train wreck in Vaughn, Mississippi, while trying to make up time on the Cannonball Express.

John Luther (“Casey”) Jones (March 14, 1863 – April 30, 1900) was an American railroad engineer from Jackson, Tennessee, who worked for the Illinois Central Railroad (IC). On April 30, 1900, he alone was killed when his passenger train, the “Cannonball Express,” collided with a stalled freight train at Vaughan, Mississippi, on a foggy and rainy night.

His dramatic death, trying to stop his train and save lives, made him a hero; he was immortalized in a popular ballad sung by his friend Wallace Saunders, an African American engine wiper for the IC.

On April 29, 1900 Jones was at Poplar Street Station in Memphis, Tennessee, having driven the No. 2 from Canton (with his assigned Engine No. 382 ). Normally, Jones would have stayed in Memphis on a layover; however, he was asked to take the No. 1 back to Canton, as the scheduled engineer (Sam Tate), who held the regular run of Trains No. 1 (known as “The Chicago & New Orleans Limited”, later to become the famous “Panama Limited”) and No. 4 (“The New Orleans Fast Mail”) with his assigned Engine No. 382, had called in sick with cramps. Jones loved challenges and was determined to “get her there on the advertised” time no matter how difficult it looked.

A fast engine, a good fireman (Simeon T. Webb would be the train’s assigned fireman), and a light train were ideal for a record-setting run. Although it was raining, steam trains of that era operated best in damp conditions. However, the weather was quite foggy that night (which reduced visibility), and the run was well-known for its tricky curves. Both conditions would prove deadly later that night.

Normally the No. 1 would depart Memphis at 11:15 PM and arrive in Canton (188 miles to the south) at 4:05 AM the following morning. However, due to the delays with the change in engineers, the No. 1 (with six cars) did not leave Memphis until 12:50 am, 95 minutes behind schedule.

The first section of the run would take Jones from Memphis 100 miles south to Grenada, Mississippi, with an intermediate water stop at Sardis, Mississippi (50 miles into the run), over a new section of light and shaky rails at speeds up to 80 mph (129 km/h). At Senatobia, Mississippi (40 miles into the run) Jones passed through the scene of a prior fatal accident from the previous November. Jones made his water stop at Sardis, then arrived at Grenada for more water, having made up 55 minutes of the 95 minute delay.

Jones made up another 15 minutes in the 25-mile stretch from Grenada to Winona, Mississippi. The following 30-mile stretch (Winona to Durant, Mississippi) had no speed-restricted curves. By the time he got to Durant (155 miles into the run) Jones was almost on time. He was quite happy, saying at one point “Sim, the old girl’s got her dancing slippers on tonight!” as he leaned on the Johnson bar.

At Durant he received new orders to take to the siding at Goodman, Mississippi (eight miles south of Durant, and 163 miles into the run) and wait for the No. 2 passenger train to pass, and then continue on to Vaughan. His orders also instructed him that he was to meet passenger train No. 26 at Vaughan (15 miles south of Goodman, and 178 miles into the run); however, No. 26 was a local passenger train in two sections and would be in the siding, so he would have priority over it. Jones pulled out of Goodman, only five minutes behind schedule, and with 25 miles of fast track ahead Jones doubtless felt that he had a good chance to make it to Canton by 4:05 AM “on the advertised”.

But the stage was being set for a tragic wreck at Vaughan. The stopped double-header freight train No. 83 (located to the north and headed south) and the stopped long freight train No. 72 (located to the south and headed north) were both in the passing track to the east of the main line but there were more cars than the track could hold, forcing some of them to overlap onto the main line above the north end of the switch. The northbound local passenger train No. 26 had arrived from Canton earlier which had required a “saw by” in order for it to get to the “house track” west of the main line. The saw by maneuver for No. 26 required that No. 83 back up and allow No. 72 to move northward and pull its overlapping cars off the south end, allowing No. 26 to gain access to the house track. But this left four cars overlapping above the north end of the switch and on the main line right in Jones’ path. As a second saw by was being prepared to let Jones pass, an air hose broke on No. 72, locking its brakes and leaving the last four cars of No. 83 on the main line.

Meanwhile, Jones was almost back on schedule, running at about 75 miles per hour toward Vaughan, unaware of the danger ahead, since he was traveling through a 1.5-mile left-hand curve which blocked his view. Webb’s view from the left side of the train was better, and he was first to see the red lights of the caboose on the main line. “Oh my Lord, there’s something on the main line!” he yelled to Jones. Jones quickly yelled back “Jump Sim, jump!” to Webb, who crouched down and jumped about 300 feet before impact and was knocked unconscious. The last thing Webb heard when he jumped was the long, piercing scream of the whistle as Jones tried to warn anyone still in the freight train looming ahead. He was only two minutes behind schedule about this time.

Jones reversed the throttle and slammed the airbrakes into emergency stop, but “Ole 382” quickly plowed through a wooden caboose, a car load of hay, another of corn and half way through a car of timber before leaving the track. He had amazingly reduced his speed from about 75 miles per hour to about 35 miles per hour when he impacted with a deafening crunch of steel against steel and splintering wood. Because Jones stayed on board to slow the train, he no doubt saved the passengers from serious injury and death (Jones himself was the only fatality of the collision). His watch was found to be stopped at the time of impact which was 3:52 AM on April 30, 1900. Popular legend holds that when his body was pulled from the wreckage of his train near the twisted rail his hands still clutched the whistle cord and the brake. A stretcher was brought from the baggage car on No. 1 and crewmen of the other trains carried his body to the depot ½-mile away.

1947 Thor Heyerdahl and five crew mates set out from Peru on the

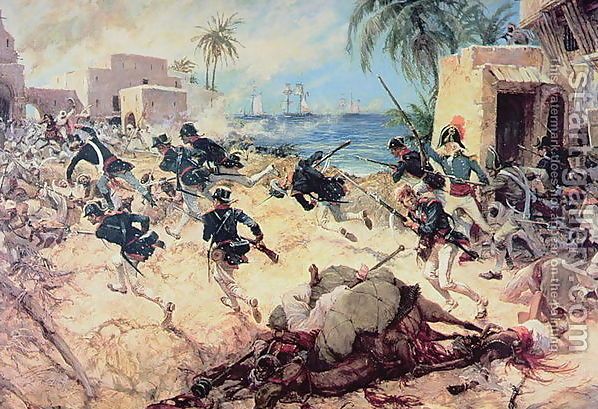

1947 Thor Heyerdahl and five crew mates set out from Peru on the  On this day in 1805, Naval Agent to the Barbary States, William Eaton, the former consul to Tunis, led an small expeditionary force of Marines, commanded by First Lieutenant Presley O’Bannon, and Berber mercenaries from Alexandria, across 500 miles to the port of Derna in Tripoli. Supported by US Naval gunfire, the port was captured by the end of the day, overthrowing Yusuf Karamanli, the ruling pasha of Tripoli, who had seized power from his brother, Hamet Karamanli, a pasha who was sympathetic to the United States.

On this day in 1805, Naval Agent to the Barbary States, William Eaton, the former consul to Tunis, led an small expeditionary force of Marines, commanded by First Lieutenant Presley O’Bannon, and Berber mercenaries from Alexandria, across 500 miles to the port of Derna in Tripoli. Supported by US Naval gunfire, the port was captured by the end of the day, overthrowing Yusuf Karamanli, the ruling pasha of Tripoli, who had seized power from his brother, Hamet Karamanli, a pasha who was sympathetic to the United States. On this day in 1986,

On this day in 1986,

On this day in 1859,

On this day in 1859,

On this day in 1564,

On this day in 1564,  On this day in 1978,

On this day in 1978,

Recent Comments