This is your morning Open Thread. Pour your favorite beverage and review the past and comment on the future.

Find the past “On This Day in History” here.

March 5 is the 64th day of the year (65th in leap years) in the Gregorian calendar. There are 301 days remaining until the end of the year.

On this day in 1770, a mob of angry colonists gathers at the Customs House in Boston and begins tossing snowballs and rocks at the lone British soldier guarding the building. The protesters opposed the occupation of their city by British troops, who were sent to Boston in 1768 to enforce unpopular taxation measures passed by a British parliament without direct American representation.

The event began on King Street, today known as State Street, in the early evening of March 5, in front of Private Hugh White, a British sentry, as he stood duty outside the Custom house. A young wigmaker’s apprentice named Edward Gerrish called out to a British officer, Captain Lieutenant John Goldfinch, that Goldfinch had not paid the bill of Gerrish’s master. Goldfinch had in fact settled his account and ignored the insult. Gerrish departed, but returned a couple of hours later with companions. He continued his complaints, and the civilians began throwing rocks at Goldfinch. Gerrish exchanged insults with Private White, who left his post, challenged the boy, and struck him on the side of the head with a musket. As Gerrish cried in pain, one of his companions, Bartholomew Broaders, began to argue with White. This attracted a larger crowd.

As the evening progressed, the crowd grew larger and more boisterous. The mob grew in size and continued harassing Private White. As bells, which usually signified a fire, rang out from the surrounding steeples, the crowd of Bostonians grew larger and more threatening. Over fifty of the Bostonian townsmen gathered and provoked White and Goldfinch into fight. As the crowd began to get larger, the British soldiers realized that the situation was about to explode. Private White left his sentry box and retreated to the Custom House stairs with his back to a locked door. Nearby, from the Main Guard, the Officer of the Day, Captain Thomas Preston, watched this situation escalate and, according to his account, dispatched a non-commissioned officer and seven or eight soldiers of the 29th Regiment of Foot, with fixed bayonets, to relieve White. He and his subordinate, James Basset, followed soon afterward. Among these soldiers were Corporal William Wemms (apparently the non-commissioned officer mentioned in Preston’s report), Hugh Montgomery, John Carroll, James Hartigan, William McCauley, William Warren and Matthew Kilroy. As this relief column moved forward to the now empty sentry box, the crowd pressed around them. When they reached this point they loaded their muskets and joined with Private White at the custom house stairs. As the crowd, estimated at 300 to 400, pressed about them, they formed a semicircular perimeter.

The crowd continued to harass the soldiers and began to throw snow balls and other small objects at the soldiers. Private Hugh Montgomery was struck down onto the ground by a club wielded by Richard Holmes, a local tavernkeeper. When he recovered to his feet, he fired his musket, later admitting to one of his defense attorneys that he had yelled “Damn you, fire!” It is presumed that Captain Preston would not have told the soldiers to fire, as he was standing in front of the guns, between his men and the crowd of protesters. However, the protesters in the crowd were taunting the soldiers by yelling “Fire”. There was a pause of indefinite length; the soldiers then fired into the crowd. Their uneven bursts hit eleven men. Three Americans – ropemaker Samuel Gray, mariner James Caldwell, and a mixed race sailor named Crispus Attucks – died instantly. Seventeen-year-old Samuel Maverick, struck by a ricocheting musket ball at the back of the crowd, died a few hours later, in the early morning of the next day. Thirty-year-old Irish immigrant Patrick Carr died two weeks later. To keep the peace, the next day royal authorities agreed to remove all troops from the centre of town to a fort on Castle Island in Boston Harbor. On March 27 the soldiers, Captain Preston and four men who were in the Customs House and alleged to have fired shots, were indicted for murder.

At the request of Captain Preston and in the interest that the trial be fair, John Adams, a leading Boston Patriot and future President, took the case defending the British soldiers.

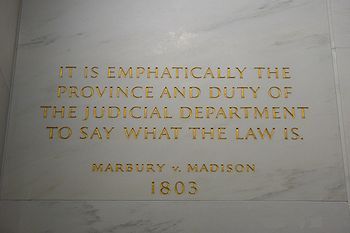

In the trial of the soldiers, which opened November 27, 1770, Adams argued that if the soldiers were endangered by the mob, which he called “a motley rabble of saucy boys, negroes, and molattoes, Irish teagues and outlandish jack tarrs,” they had the legal right to fight back, and so were innocent. If they were provoked but not endangered, he argued, they were at most guilty of manslaughter. The jury agreed with Adams and acquitted six of the soldiers. Two of the soldiers were found guilty of manslaughter because there was overwhelming evidence that they fired directly into the crowd, however Adams invoked Benefit of clergy in their favor: by proving to the judge that they could read by having them read aloud from the Bible, he had their punishment, which would have been a death sentence, reduced to branding of the thumb in open court. The jury’s decisions suggest that they believed the soldiers had felt threatened by the crowd. Patrick Carr, the fifth victim, corroborated this with a deathbed testimony delivered to his doctor.

Three years later in 1773, on the third anniversary of the incident, John Adams made this entry in his diary:

The Part I took in Defence of Cptn. Preston and the Soldiers, procured me Anxiety, and Obloquy enough. It was, however, one of the most gallant, generous, manly and disinterested Actions of my whole Life, and one of the best Pieces of Service I ever rendered my Country. Judgment of Death against those Soldiers would have been as foul a Stain upon this Country as the Executions of the Quakers or Witches, anciently. As the Evidence was, the Verdict of the Jury was exactly right.

“This however is no Reason why the Town should not call the Action of that Night a Massacre, nor is it any Argument in favour of the Governor or Minister, who caused them to be sent here. But it is the strongest Proofs of the Danger of Standing Armies.

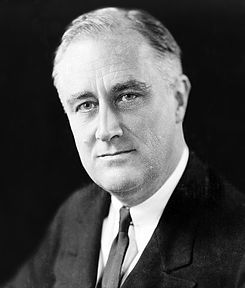

In this day in 1933, at the height of the Great Depression,

In this day in 1933, at the height of the Great Depression,  On this day in 1887,

On this day in 1887,  On this day in 1836, the

On this day in 1836, the  The Republic of Texas was created from part of the Mexican state

The Republic of Texas was created from part of the Mexican state  On this day in 1961, President John F. Kennedy issues Executive Order #10924,

On this day in 1961, President John F. Kennedy issues Executive Order #10924,  The

The  DNA was first isolated by the Swiss physician

DNA was first isolated by the Swiss physician  On this day in 1827,

On this day in 1827,

In 1897 acting Yellowstone superintendent Colonel S.B.M. Young proposed expanding that park’s borders south to encompass the northern extent of Jackson Hole in order to protect migrating herds of elk. Next year,

In 1897 acting Yellowstone superintendent Colonel S.B.M. Young proposed expanding that park’s borders south to encompass the northern extent of Jackson Hole in order to protect migrating herds of elk. Next year,  In 1928, a Coordinating Commission on National Parks and Forests met with valley residents and reached an agreement for the establishment of a park. Wyoming Senator

In 1928, a Coordinating Commission on National Parks and Forests met with valley residents and reached an agreement for the establishment of a park. Wyoming Senator  On this day in Japan, the Plum Blossom Festival is held. The Festival at the

On this day in Japan, the Plum Blossom Festival is held. The Festival at the

On this day in

On this day in

Recent Comments