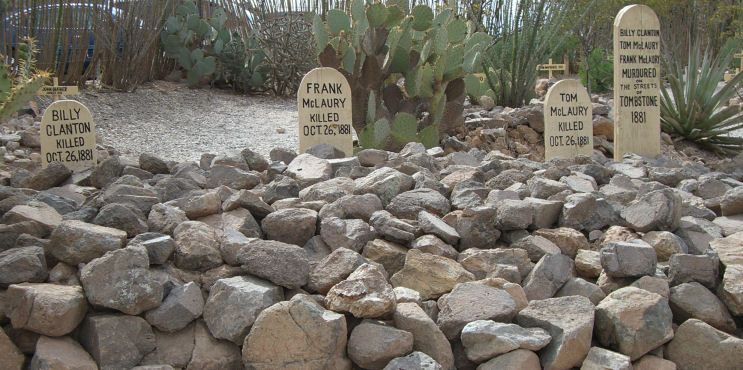

On this day in 1881, the Earp brothers face off against the Clanton-McLaury gang in a legendary shootout at the OK Corral in Tombstone, Arizona.

On the morning of October 25, Ike Clanton and Tom McLaury came into Tombstone for supplies. Over the next 24 hours, the two men had several violent run-ins with the Earps and their friend Doc Holliday. Around 1:30 p.m. on October 26, Ike’s brother Billy rode into town to join them, along with Frank McLaury and Billy Claiborne. The first person they met in the local saloon was Holliday, who was delighted to inform them that their brothers had both been pistol-whipped by the Earps. Frank and Billy immediately left the saloon, vowing revenge.

Around 3 p.m., the Earps and Holliday spotted the five members of the Clanton-McLaury gang in a vacant lot behind the OK Corral, at the end of Fremont Street. The famous gunfight that ensued lasted all of 30 seconds, and around 30 shots were fired. Though it’s still debated who fired the first shot, most reports say that the shootout began when Virgil Earp pulled out his revolver and shot Billy Clanton point-blank in the chest, while Doc Holliday fired a shotgun blast at Tom McLaury’s chest. Though Wyatt Earp wounded Frank McLaury with a shot in the stomach, Frank managed to get off a few shots before collapsing, as did Billy Clanton. When the dust cleared, Billy Clanton and the McLaury brothers were dead, and Virgil and Morgan Earp and Doc Holliday were wounded. Ike Clanton and Claiborne had run for the hills.

Aftermath

The funerals for Clanton and the McLaurys (who were relatively wealthy men) were the largest ever seen in Tombstone, drawing over 2,000 people. The fear of the Cowboys caused many Tombstone residents and businesses to reconsider their calls for the mass killing of Cowboys. Although rowdy, the Cowboys brought substantial business into Tombstone.

The fear of Cowboy retribution and the potential loss of investors because of the negative publicity in large cities such as San Francisco started to turn the opinion somewhat against the Earps and Holliday. Stories that Ike Clanton and Tom McLaury were unarmed, and that Billy Clanton and Tom McLaury even threw up their hands before the shooting, now began to make the rounds. Soon, another Clanton brother (Phineas “Fin” Clanton) had arrived in town, and some began to claim that the Earps and Holliday had committed murder, instead of enforcing the law.

The Spicer hearing

After the gunfight, Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday (the two men not formally employed as law officers, and the two least wounded) were charged with murder. After extensive testimony at the preliminary hearing to decide if there was enough evidence to bind the men over for trial, the presiding Justice of the Peace Wells Spicer ruled that there was not enough evidence to indict the men. Two weeks later, a grand jury followed Spicer’s finding, and also refused to indict. Spicer, in his ruling, criticized City Marshal Virgil Earp for using Wyatt and Doc as backup temporary deputies, but not for using Morgan, who had already been wearing a City Marshal badge for nine days. However, it was noted that if Wyatt and Holliday had not backed up Marshal Earp, then he would have faced even more overwhelming odds than he had, and could not possibly have survived.

The participants in later history

A few weeks following the grand jury refusal to indict, Virgil Earp was shot by hidden assailants from an unused building at night – a wound causing him complete loss of the use of his left arm. Three months later Morgan Earp was murdered by a shot in the back in Tombstone by men shooting from a dark alley.

A few weeks following the grand jury refusal to indict, Virgil Earp was shot by hidden assailants from an unused building at night – a wound causing him complete loss of the use of his left arm. Three months later Morgan Earp was murdered by a shot in the back in Tombstone by men shooting from a dark alley.

After these incidents, Wyatt, accompanied by Doc Holliday and several other friends, undertook what has later been called the Earp vendetta ride in which they tracked down and killed the men whom they believed had been responsible for these acts. After the vendetta ride, Wyatt and Doc left the Arizona Territory in April, 1882 and parted company, although they remained in contact.

Billy Claiborne was killed in a gunfight in Tombstone in late 1882, by gunman Franklin Leslie.

Ike Clanton was caught cattle rustling in 1887, and shot dead by lawmen while resisting arrest.

Later in 1887, just over six years from the time of the O.K. fight, Doc Holliday died of tuberculosis in Glenwood Springs, Colorado, aged 36.

Later in 1887, just over six years from the time of the O.K. fight, Doc Holliday died of tuberculosis in Glenwood Springs, Colorado, aged 36.

Virgil Earp served as the “Town Marshal,” hired by the Southern Pacific RR, in Colton, California. He lived without the use of his arm, although continued as a lawman in California, and died of pneumonia at age 62 in 1905, still on the job as a peace officer.

Johnny Behan failed even to be re-nominated by his own party for the sheriff race in 1882, and never again worked as a lawman, spending the rest of his life at various government jobs, dying in Tucson of natural causes at age 67 in 1912.

Wyatt Earp, the last survivor of the fight, traveled across the western frontier for decades in the company of Josephine Marcus, working mostly as a gambler, and eventually died in Los Angeles of infection, in 1929, at the age of 80.

Wyatt Earp, the last survivor of the fight, traveled across the western frontier for decades in the company of Josephine Marcus, working mostly as a gambler, and eventually died in Los Angeles of infection, in 1929, at the age of 80.

A legacy of questions

The issue of fault at the O.K. Corral shooting has been hotly debated over the years. To this day, Pro-Earp followers view the gunfight as a struggle between “Law-and-order” against out-of-control Cowboys; Pro-Clanton/McLaury followers view it as a political vendetta and abuse of authority.

A recent attempt to reinvestigate part of the matter aired on an episode of Discovery Channel’s Unsolved History using modern technology to re-enact the shotgun shooting which was part of the incident. However, the re-enactment did not use 19th century period technology (a late 19th century shotgun messenger type short shotgun, brass cases, black powder). The episode concluded that Doc Holliday may have triggered the fight by cocking both barrels of his shotgun, but was likely not the first shooter.

In April 2010, original transcripts of witness statements were rediscovered in Bisbee, Arizona, and are currently being preserved and digitized. Photocopies of these documents have been available to researchers since 1960, and new scans of them will be made available for public viewing online.

A few weeks following the grand jury refusal to indict, Virgil Earp was shot by hidden assailants from an unused building at night – a wound causing him complete loss of the use of his left arm. Three months later Morgan Earp was murdered by a shot in the back in Tombstone by men shooting from a dark alley.

A few weeks following the grand jury refusal to indict, Virgil Earp was shot by hidden assailants from an unused building at night – a wound causing him complete loss of the use of his left arm. Three months later Morgan Earp was murdered by a shot in the back in Tombstone by men shooting from a dark alley. Later in 1887, just over six years from the time of the O.K. fight, Doc Holliday died of tuberculosis in Glenwood Springs, Colorado, aged 36.

Later in 1887, just over six years from the time of the O.K. fight, Doc Holliday died of tuberculosis in Glenwood Springs, Colorado, aged 36. Wyatt Earp, the last survivor of the fight, traveled across the western frontier for decades in the company of Josephine Marcus, working mostly as a gambler, and eventually died in Los Angeles of infection, in 1929, at the age of 80.

Wyatt Earp, the last survivor of the fight, traveled across the western frontier for decades in the company of Josephine Marcus, working mostly as a gambler, and eventually died in Los Angeles of infection, in 1929, at the age of 80.

Bearing the inscription “An Unknown American who gave his life in the World War,” the chosen casket traveled to Paris and then to Le Havre, France, where it would board the cruiser Olympia for the voyage across the Atlantic. Once back in the United States, the Unknown Soldier was buried in Arlington National Cemetery, near Washington, D.C.

Bearing the inscription “An Unknown American who gave his life in the World War,” the chosen casket traveled to Paris and then to Le Havre, France, where it would board the cruiser Olympia for the voyage across the Atlantic. Once back in the United States, the Unknown Soldier was buried in Arlington National Cemetery, near Washington, D.C.

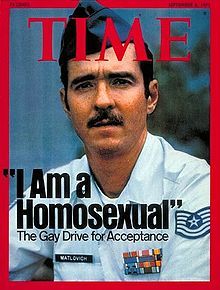

On June 22, 1988, less than a month before his 45th birthday, Matlovich died of complications from HIV/AIDS beneath a large photo of Martin Luther King, Jr. His tombstone, meant to be a memorial to all gay veterans, does not bear his name. It reads, “When I was in the military, they gave me a medal for killing two men and a discharge for loving one.” Matlovich’s tombstone at Congressional Cemetery is on the same row as that of FBI Director

On June 22, 1988, less than a month before his 45th birthday, Matlovich died of complications from HIV/AIDS beneath a large photo of Martin Luther King, Jr. His tombstone, meant to be a memorial to all gay veterans, does not bear his name. It reads, “When I was in the military, they gave me a medal for killing two men and a discharge for loving one.” Matlovich’s tombstone at Congressional Cemetery is on the same row as that of FBI Director

In 1939, the Guggenheim Foundation’s first museum, “The Museum of Non-Objective Painting”, opened in rented quarters at 24 East Fifty-Fourth Street in New York and showcased art by early modernists such as

In 1939, the Guggenheim Foundation’s first museum, “The Museum of Non-Objective Painting”, opened in rented quarters at 24 East Fifty-Fourth Street in New York and showcased art by early modernists such as  Internally, the viewing gallery forms a gentle helical spiral from the main level up to the top of the building. Paintings are displayed along the walls of the spiral and also in exhibition space found at annex levels along the way.

Internally, the viewing gallery forms a gentle helical spiral from the main level up to the top of the building. Paintings are displayed along the walls of the spiral and also in exhibition space found at annex levels along the way.

Recent Comments