(2 pm. – promoted by ek hornbeck)

cross-posted from Voices on the Square

The Northeast Indiana Passenger Rail Association, on 28 June 2013, announced the results of their study of a Northern Indiana / Ohio rail corridor to Chicago:

The Northeast Indiana Passenger Rail Association, on 28 June 2013, announced the results of their study of a Northern Indiana / Ohio rail corridor to Chicago:

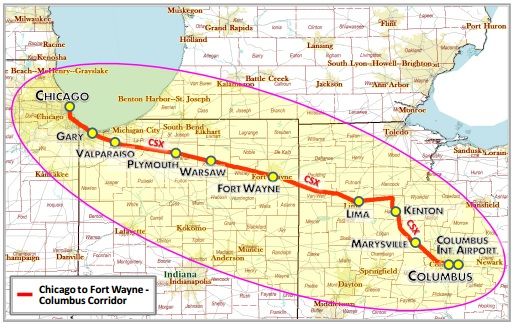

The proposed system would operate twelve trains each way per day, including at least six express schedules. With modern diesel equipment running at speeds of up to 110 miles per hour to start, the three-hundred mile trip between downtown Chicago and downtown Columbus would normally require only three hours, forty-five minutes (express service), or four hours (local service). Track and safety improvements in a potential future phase would support speeds up to 130 mph and a downtown Chicago to downtown Columbus express time of three hours, twenty minutes.

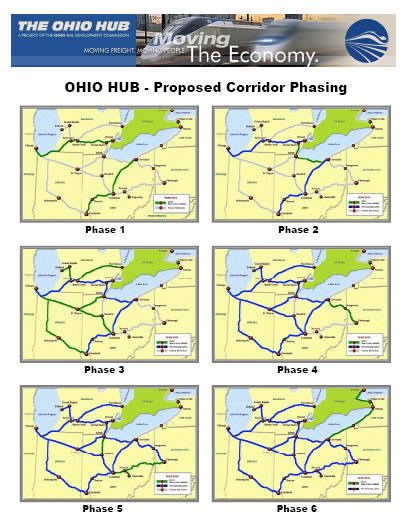

Longer time readers of the Sunday Train may recognize this as a piece of the Ohio Hub project, first developed in the 1990’s. At the time that the Ohio Hub was originally developed, the Fort Wayne to Chicago link was slated to be the second connection from Ohio to Chicago, with the envisioned phasing being:

- Phase 1: Chicago to Detroit; and Cincinnati – Columbus – Cleveland ~ the Triple C backbone of the Ohio Hub

- Phase 2: Cleveland to Toledo, Toledo to Detroit, completing Cleveland to Chicago via Michigan

- Phase 3: Fort Wayne to Chicago; Toledo to Fort Wayne; Columbus to Fort Wayne; Cincinnati – Indianapolis – Gary – Chicago, completing Dayton/Cincinnati to Chicago via Indianapolis and Columbus/Cleveland to Chicago via Fort Wayne

- Phase 4: Cleveland to Pittsburgh via Youngstown, connecting with services to Philadelphia / New York on the Keystone Corridor

- Phase 5: Columbus to Pittsburgh, connecting with services to Philadelphia / New York on the Keystone Corridor

- Phase 6: Cleveland to Toronto via Buffalo and Niagara Falls, connecting with services to New York and Boston on the Empire Corridor

So what the Northeast Indiana Passenger Rail Association is doing is pulling out a section of the Phase Three of the Ohio Hub and proposing it as a free-standing project. This free-standing project would bring intercity rail service back to Columbus, the largest or second largest urban area lacking rail service (depending on how you count Phoenix), and to Fort Wayne, the largest urban area in Indiana without intercity passenger rail service.

Columbus to Chicago via Fort Wayne by the Numbers

As described above, this is not a bullet train High Speed Rail proposal. It is rather what I have taken to calling a Rapid Rail proposal. Unlike conventional Amtrak services, this is faster than driving, and door-to-door it is faster than air travel for the intermediate cities to either end, but it is not faster than air travel door-to-door between Columbus and Chicago. The economic cost/benefit of this project therefore does not rest on capturing an extremely large share of intercity passenger traffic on this corridor, but rather on having relatively low capital costs, with the study completed by TEMS Inc. [executive summary, pdf] estimating a capital (one-off) cost of $4m per mile, for a total capital cost of about $1.3b.

As described above, this is not a bullet train High Speed Rail proposal. It is rather what I have taken to calling a Rapid Rail proposal. Unlike conventional Amtrak services, this is faster than driving, and door-to-door it is faster than air travel for the intermediate cities to either end, but it is not faster than air travel door-to-door between Columbus and Chicago. The economic cost/benefit of this project therefore does not rest on capturing an extremely large share of intercity passenger traffic on this corridor, but rather on having relatively low capital costs, with the study completed by TEMS Inc. [executive summary, pdf] estimating a capital (one-off) cost of $4m per mile, for a total capital cost of about $1.3b.

To put that cost in perspective:

- That is about $250 per passenger over 2020 to 2040 on the projected ridership

- That is 77% of estimated economic benefits at a 7% discount rate and 59% of estimated economic benefits at a 3% discount rate

- Compared to the 1.9m population of the towns and urban areas being connected to Chicago (I use city populations for areas without urban area population rather than metro area population for this), that is $679 per person in the cities and towns served.

This is preliminary planning. The next phase would be engaging in an Environmental Impact Report. Since this is a project that engaged in improvements of existing operating rail corridors, including substantial upgrades to level crossings to provide four-gate level crossings and Positive Train Control along the route, it is quite unlikely that the Environmental Impact Report will turn up any substantial problems, but it is still work that must be done before the project can be considered for Federal funding.

And then the next phase would be to win support from Ohio and Indiana for the required 20% of local funds, about $260m, and apply for Federal funding for 80% of the capital costs, about $1.04b. Of course, this is completely infeasible under present political conditions, but the earliest the project could start construction would be 2016 in any event, so that its quite reasonable to target this for 2017. So the Fort Wayne-based Northeast Indiana Passenger Rail Association (NIPRA) is engaged in what may be termed opportunistic planning, laying the groundwork and trying to recruit political allies so that if there is a shift in the current political climate, they will be positioned to take advantage of the opening.

If the capital works are performed, the rail service that they propose can be operated at a surplus, assuming tickets costing 2/3 current equivalent air tickets. Therefore they are not proposing a subsidized public authority to operate the service. Rather, they propose that the public authority that develops the corridor will franchise out the operation of the service.

The economic benefits of the service are estimated to result in increases in Federal tax revenues of $894m, State tax payments of $345m, and local Property tax payments of $694m. These are cumulative increases over the life of the project, but it does help illustrate why NIPRA has been making presentations in affected cities, including importantly Columbus, Ohio (10TV report), since at the level of state public finances, this is in effect state investment in local economic benefit, which would be a reversal of the trend under the Republican-controlled state governments has been to shirk state spending at the expense of pushing local budgets into the red.

A New Ohio Hub

I do not know what the odds are that NIRPA will be successful in getting this project launched. Indeed, in a real sense it is impossible to know these odds, since they depend upon political fortunes of various forces within both the Democratic and Republican parties at both the national and state levels in both the 2014 and 2016 election cycles. To take just one example, an ascendent “Tea Party” wing of the national Republican Party in 2017 could easily put the project on the back burner until 2021 at the earliest, while a “Tea Party” wing in defeat and disarray and a resurgance in power and influence of local Chamber of Commerce type Republicans would make for much more favorable political terrain.

I do not know what the odds are that NIRPA will be successful in getting this project launched. Indeed, in a real sense it is impossible to know these odds, since they depend upon political fortunes of various forces within both the Democratic and Republican parties at both the national and state levels in both the 2014 and 2016 election cycles. To take just one example, an ascendent “Tea Party” wing of the national Republican Party in 2017 could easily put the project on the back burner until 2021 at the earliest, while a “Tea Party” wing in defeat and disarray and a resurgance in power and influence of local Chamber of Commerce type Republicans would make for much more favorable political terrain.

However, if NIPRA is successful in winning support for this project, it lays the foundation for an entirely different phasing of the Ohio Hub system than the original plan ~ so this is by contrast to the original phasing illustrated above:

- Phase 1: Chicago to Fort Wayne to Columbus

- Phase 2: Cleveland to Toledo, Toledo to Fort Wayne

- Phase 3: Pittsburgh to Cleveland; Pittsburgh to Columbus; Toledo to Detroit

- Phase 4: Chicago – Lafayette – Indianapolis; Cincinnati to Columbus to Cleveland

- Phase 5: Cleveland to Buffalo to Toronto; Cincinnati to Indianapolis

In Phase 2, not only is a Cleveland to Chicago day corridor established, but one of the Amtrak services that run through Cleveland in the middle of the night may be re-routed to run on the 110mph corridor from Chicago to Cleveland in the afternoon/evening and then from Cleveland at 7:30pm to New York as a sleeper train arriving 8:15am.

In Phase 3, multiple Chicago / Pittsburgh trains via both Cleveland and Columbus connect with planned increase in Keystone Corridor services connecting Pittsburgh to Philadelphia and New York, with connections in Philadelphia to Maryland, DC and Virginia via Amtrak Acela and Northeast Regional services.

In Phase 4, the political base of the Triple-C corridor has gained substantial leverage since in addition to the primary access Cincinnati/Columbus, Dayton/Cincinnati and Dayton/Columbus, and secondary access Cincinnati/Cleveland, it gives Cincinnati/Dayton access to both the East Coast and Toledo/Detroit via Columbus. The political leverage for upgrading the existing once-a-day Indianapolis to Chicago via Lafayette corridor is not the Route Matrix as much as envy-thy-neighbor, with Fort Wayne having enjoyed the benefits of two hour connections to Chicago since Phase 1, and Indianapolis still relegated to the once a day, slower-than-driving four hour Amtrak service. And, of course, it is because the Amtrak service has a transit speed slower than driving that it is limited to once a day, since unlike the Rapid Rail services, the slow long-haul Amtrak operations require operating subsidies.

Phase 5 completes the Ohio Hub with the two corridors that would not offer the prospect of an operating surplus without other parts of the system already be in place, with the Indianapolis / Cincinnati link sharing Cincinnati/Dayon – Chicago, Cincinnati/Dayton – Indianapolis and Columbus – Indianapolis patronage, and the Cleveland – Buffalo – Niagara Falls – Toronto corridor collecting patronage from Cleveland, Columbus, Cincinnati/Dayton, Detroit/Toledo and Chicago.

None of this involves establishing an all-new rail corridor. Most of these are rail corridors presently in active use, with the capacity for the new passenger services provided by other 10 miles of passing track per 50 miles of running track or a third dedicated passenger track in higher freight traffic areas with dedicated freight tracks each way. Two sections, between Toledo and Detroit, and between Columbus and Pittsburgh, included retired rail corridor that have been reserved for use as rail corridors.

Therefore, the pace at which phases of this project can be rolled out depend largely upon whether or not a reliable source of funding can be established. If so, then it would be possible to commence the Environmental Impact Analysis of later phases as construction commences on the first phase, begin construction on the following phase while construction is being completed on the preceding phase, and roll out one completed phase per year. Indeed, if federal transport policy was not in paralysis, and if we had started the original Amtrak-Speed Triple C section of the Ohio Hub in 2011, that would have gone into service last year, the upgrade to 110mph could have been completed this year, and we could have been putting this Columbus to Chicago via Fort Wayne section into service in 2016, with a completed Ohio Hub available by 2021 by the earliest.

On the other hand, if we have to pursue the kind of opportunistic strategy that NIPRA is pursuing for each stage of the system, lobbying to get Environmental Impact Analyses done and having a shovel-ready projects available for the next time that funding becomes available, there is no telling how long it might take.

Beyond the Cost/Benefit Analysis

Part of the Rules of the Game for the kind of Cost/Benefit Analysis performed for the Columbus is that it is performed under the assumption that current conditions prevail for the indefinite future.

Part of the Rules of the Game for the kind of Cost/Benefit Analysis performed for the Columbus is that it is performed under the assumption that current conditions prevail for the indefinite future.

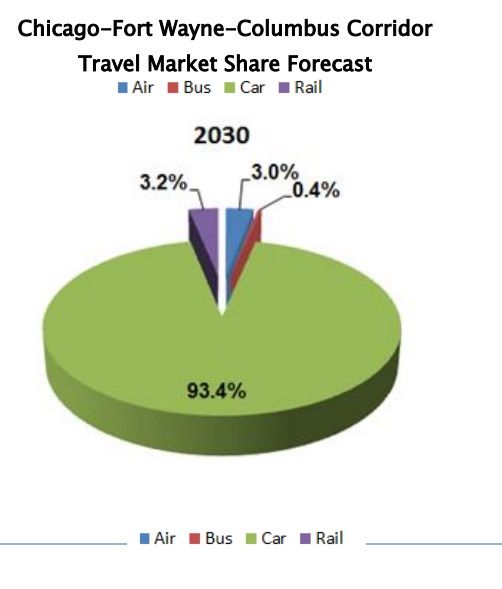

And it is under those conditions that this is a transport service of secondary importance in the larger urban areas of Chicago and Columbus, only rising to primary importance as a transport option in the smaller towns and urban areas along the route. The total transport market in this route is dominated by car transport, as shown in this market share projection if this service is established. Of course, the total capital investment in highways in this region ~ Interstate, National, State, County and Township Highways ~ is an even larger share of total capital spending for intercity transport, with estimates of new road construction costs running from $1.7m per mile for a two lane undivided rural road with paved shoulders to $4.2m for a divided four lane rural Interstate highway.

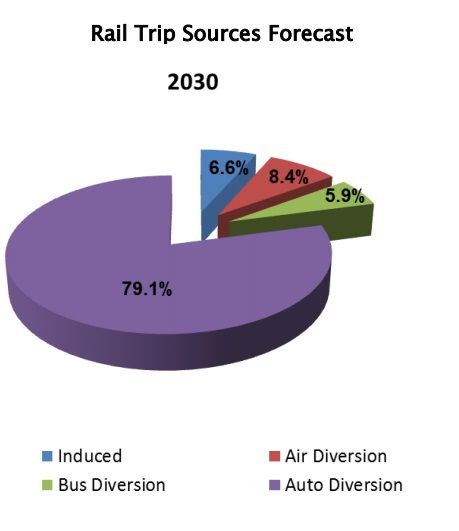

Given the current dominance of car travel for all travel along this corridor, it is also no surprise that the large majority of patronage for this rail service, about 80%, is projected to be from existing car trips. This kind of Rapid Rail service is far more in competition with car trips than with air travel, which provides less than 9% of total rail trips and when competing against rail is projected to account only 3% of total travel in this corridor. People switching from Bus to Rail are projected to account for under 6% of total rail trips, and account for less than 1% of total travel in this market if the rail service is established.

But this is all under status quo conditions. And we know that the cheap source of petroleum from the large oil fields discovered in the 1930’s through 1950’s are becoming depleted, while the new petroleum sources that we have been finding since then are either smaller pockets of oil, in remote and difficult to access areas in polar or deep sea locations, or are energy-intensive and water-intensive deposits in non-porous rock or uncapped deposits of tar which the liduid and gas portion long since lost.

But this is all under status quo conditions. And we know that the cheap source of petroleum from the large oil fields discovered in the 1930’s through 1950’s are becoming depleted, while the new petroleum sources that we have been finding since then are either smaller pockets of oil, in remote and difficult to access areas in polar or deep sea locations, or are energy-intensive and water-intensive deposits in non-porous rock or uncapped deposits of tar which the liduid and gas portion long since lost.

So we know that coming changes in the status quo are biased toward more expensive gasoline and other petroleum products. The uncertainty is not whether gas prices that were unimaginable ten years ago will become the norm, but rather how quickly and whether we are talking a real (corrected for inflation) price of $6/gallon or $10/gallon.

So on top of the estimated economic benefits under status quo conditions, we know that this project also offered implicit insurance against severe oil price shocks. Part of this is automatic, since Rapid Rail with diesel power is more energy efficient than both conventional Amtrak Rail and intercity automobile transport, when operated at the high occupancy that a gas price shock would make likely. And if we encounter not just price shocks but also supply interruptions, bio-diesel is a more compatible substitute for petro-diesel than various liquid bio-fuels as replacements for gasoline.

If the price shock is a permanent state of affairs rather than a temporary emergency, the implicit insurance extended to the prospect for electrification of the rail corridor. It is, after all, simpler and less expensive to electrify an existing passenger rail corridor than it is to electrify an equivalent share of our automobile transport system. We could clearly electrify from Chicago to Fort Wayne, Fort Wayne to Columbus, and Columbus to Pittsburgh in three phases, completing a phase per year once the Environmental Impact Analysis of the first phase has been completed. Indeed, with hybrid 125mph passenger rail locomotives already in use overseas, we could begin to take advantage of a corridor electrification project as each phase is completed.

Further, in conditions of an oil price shock, the use of the electrified transport would not be limited to passenger trains. Electrification of a corridor from Chicago to Pittsburgh via Columbus from the one side, and electrification of the Keystone West corridor from Harrisburg, PA to Pittsburgh PA from the other side would offer an electric container freight rail corridor from northern New Jersey through to Chicago.

Conversations, Considerations and Contemplations

This appears, to my eyes, to be a sound project which warrants public capital investment to establish a corridor in which to franchise operation of a passenger service, and so I will be adopting a watching brief on the work of the Northeast Indiana Rail Passenger Association.

And now, as always, rather looking for some overarching conclusion, I now open the floor to the comments of those reading.

If you have an issue on some other area of sustainable transport or sustainable energy production, please feel free to start a new main comment. To avoid confusing me, given my tendency to filter comments through the topic of this week’s Sunday Train, feel free to use the shorthand “NT:” in the subject line when introducing this kind of new topic.

And if you have a topic in sustainable transport or energy that you want me to take a look at in the coming month, be sure to include that as well.

1 comments

Author

… and Mississippi River Valley … otherwise the middle of our country between the Appalachians and the Rockies might be as dry as the Red Center of the Australian Outback.