(4 pm. – promoted by ek hornbeck)

You don’t need a Hubble telescope to explore frontiers. Of the roughly 400,000 species of plants on this planet about 70,000 are still a complete mystery to science. Unlike the space frontier, since it is estimated that about twenty-five percent of the plant species on this planet will be wiped out in the very near future, there is a sense of urgency to systematic botany.

Recently I attended a New York Botanical Garden lecture “Briefings From the Field: The Frontiers of Plant Discovery and Conservation.” Field studies are more exciting than you would expect. The first time I was invited to hear these Indiana Jones type stories that range from Ewok lifestyles in the treetops of Costa Rica to high-water adventures on the “Amazon Queen” was back in 1987.

In those few years there have been big changes in both science and the interactions with governments and industry to report. From 1987 when tropical rain forest covered only six percent of the earth’s land surface to now with only five percent left, the stories were less about adventure and more about political advances scientist are making in the conservation mission.

Below the fold are some of the facts I learned at this year’s lecture, either advances in an improving landscape or a last ditch effort to save biodiversity, you decide.

The New York Botanical Garden is an advocate for the plant kingdom…

Since most people think of the New York Botanical Garden as 250 acres of beautiful Bronx parkland, there should be a little introduction to the 23 acre scientific campus on those grounds and how worldwide field research comes together there. As far a spreading scientist across the globe, the NYBG represents the botanical graduate studies program to the world. In the area of scientific research, with worldwide field studies specializing in the Americas coming back to the Bronx to be studied at that 23 acre scientific campus and collected for the largest herbarium in the western hemisphere, a more proper title might be The New World Botanical Garden.

The setting for “Briefings From the Field: The Frontiers of Plant Discovery and Conservation” was the auction house Southerby’s and the audience were patrons and donors. To claim that the fund raising scientist sounded any more desperate than they did when I first heard them twenty-four years ago would be a case of an environmentalist putting words in the mouths of scientist. The lecture was a far different atmosphere than the doom and gloom message of the environmentalist that seems necessary to counter the global warming deniers who control the nation debate.

What I heard was a story of hope. Now there are advances in scanning electron microscopy and microscopic analysis, tools like powerful computers and software programs to analyzing massive data sets. There are Geographic Information Systems that form digital maps with multiple electronic layers and the promise of DNA sequencing offering a whole new world of possibilities. It was a story of privilege, working at “a pure research institution, with projects more diverse than research in universities and pharmaceutical companies.” The message today being the this is the “century of biology” and the wealth of new technologies is changing the approach to science for botanists seeking answers to the mysteries of life.

Along with the romance of extended camping trips in remote areas and that “Ah ha” moment of being the first human to discover a plant species, there were the hope found in the Barcode of Life (BOL) an initiative to sample all the species of trees of the world. A hope that someday researchers will create a DNA Bank Catalog that will extend to all plants, so that we can fully understand the paternity of the plant kingdom and “Darwin’s Tree of Life.” The hope of increasing scientific knowledge is a message of conservation. Dr. James S. Miller, who is the Dean and Vice President for Science at the International Plant Science Center said “An adequate understanding of the flora and vegetation of a place is a fundamental prerequisite for the conservation and sustainable use of the species that comprise other ecosystems.”

Since I first attended one of these lectures to watch a slide show about Amazon river adventures and hear Scott Mori tell stories of life in the Brazilian treetops much more is understood about about biodiversity but one message stays the same. Many of the still-existing forest areas of the tropics are still completely unexplored botanically. There was some desperation in the voice of James S. Miller as he talked of extensive Caribbean research where just twenty percent of the flora still exist and the coastal forest of Brazil where only seven percent remains. “We are racing against the clock to explore and inventory poorly known regions, particularly in the tropics where diversity is greatest, while we continue to lose more than 50,000 square miles of forest each year, an area slightly greater than the state of Mississippi. With sufficient resources, it seems plausible that botanists could complete the first comprehensive inventory of all of the world’s plant species within the next decade.”

There are also very positive stories. While not the focus of this year’s lecture the stories of Amazon field studies that can be found on page 51 of Scientific Research at the New York Botanical Garden (pdf.) focus on very successful work. NYBG field studies go back as far as 1881 in the Amazon river basin and 47 years of continuous collaboration in various areas has created much positive influence on the future of millions of acres of forest and several million forest dwellers. While the Amazon basin is far too large an area to manage a story of scientific exchange, like the ongoing 18 year old program shared with the University of Acre in Brazil, offers an improving future. Also a story of cultural exchange as rain forest residents go to the Bronx for graduate studies at the NYBG and then return home to influence the social dynamic where natural habitat is concerned. “Botanical Garden scientist create and seize opportunities to contribute to public policy in Amazonia. These opportunities for policy input will only increase as the garden strengthens its collaborations in Amazonia, and as it continues to enhance its agility and creativity with large sets of biodiversity data”

What NYBG scientist are doing for us and our planet today can’t really be answered by comparing lectures from twenty-four years ago to now. Since it seems that “sufficient resources” is unlikely, at least in these times, perhaps it is more important to understand what they and all scientific endeavors cannot achieve today by looking back at the time the New York Botanical Gardens was founded and compare that era with the politics of today. It was the late 19th century, supposedly the last time that politics were as partisan as today but science seemed more respected by our elected officials. As a young nation was looking for a position of world leadership, science was embraced. As New York City was hoping to achieve the heights of the great European cities, austerity was rejected by both government and industry.

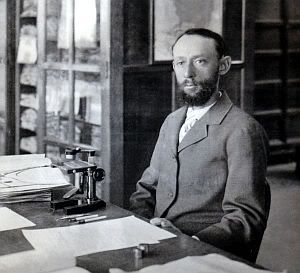

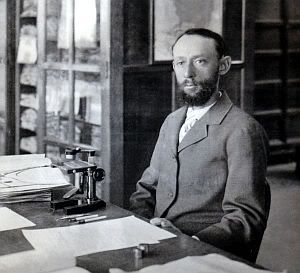

On April 18, 1891, the land was set aside by the New York State Legislature for the creation of “a public botanic garden of the highest class” for the City of New York. Prominent civic leaders and financiers, including Andrew Carnegie, Cornelius Vanderbilt, and J. Pierpont Morgan, agreed to match the City’s commitment to finance the buildings and improvements, initiating a public-private partnership that continues today. In 1896 The New York Botanical Garden appointed Nathaniel Lord Britton its first director.

Of course the creation of “250 acres of sweeping landscapes and curated gardens with expansive forests and artful plantings” wasn’t just the work of two people. Even the scientific strength of the NYBG could be traced back as far as the American father of botany, John Bartram’s efforts from Philadelphia. Perhaps the New Yorker John Torrey, the father of the Torrey Botanical Club deserves more credit. Even John Torrey’s most famous student Asa Gray had a influence from Harvard University.

Of course the creation of “250 acres of sweeping landscapes and curated gardens with expansive forests and artful plantings” wasn’t just the work of two people. Even the scientific strength of the NYBG could be traced back as far as the American father of botany, John Bartram’s efforts from Philadelphia. Perhaps the New Yorker John Torrey, the father of the Torrey Botanical Club deserves more credit. Even John Torrey’s most famous student Asa Gray had a influence from Harvard University.

The NYBG was an American effort but the Bronx as the borough of conservation dates back to Elizabeth Gertrude Knight Britton (1858-1934) and Nathaniel Lord Britton (1875-1934). On a visit to London they were inspired to emulate both the plant science and beautiful grounds of The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

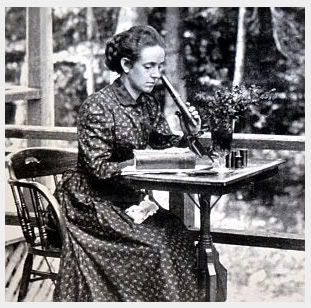

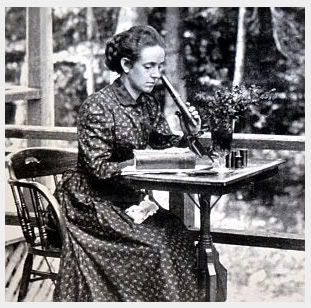

When I was young I was taught that Elizabeth Gertrude Knight Britton acted as the inspiration for the garden grounds and Nathaniel Lord Britton was given credit as the founder of the NYBG and the science programs but it was never as simple as that. Elizabeth Gertrude Knight was more the driving force behind the 1891 founding of the New York Botanical Garden than an inspiration. Knight was quite an amazing woman who was considered one of the leading experts in her field of bryology (the study of mosses) and in 1879, prior to her marriage to the first director of the NYBG, she was elected to the Torrey Botanical Club.

Besides her work in making the NYBG a possible Elizabeth Britton was also one of 25 founding members of the Botanical Society of America and launched several public efforts to preserve wildflowers including being the founder of the Wildflower Preservation Society of America. In 1906, an era when professional opportunities were sharply limited for women, she saw her name included with a star in the first edition of American Men of Science. The “starred” scientists were those whom the editors considered the top 1,000 scientists in the United States.

Besides her work in making the NYBG a possible Elizabeth Britton was also one of 25 founding members of the Botanical Society of America and launched several public efforts to preserve wildflowers including being the founder of the Wildflower Preservation Society of America. In 1906, an era when professional opportunities were sharply limited for women, she saw her name included with a star in the first edition of American Men of Science. The “starred” scientists were those whom the editors considered the top 1,000 scientists in the United States.

Even a brief glimpse at the life of the woman who spearheaded the committee that succeeded in establishing the New York Botanical Garden goes way beyond a mere long and distinguished career. Her accomplishments included teaching and lecturing at Columbia University. The devotions and achievements, having a hand in the design of the NYBG garden and education department combined with the fact that she published nearly 350 scientific works during her life makes Elizabeth Gertrude Knight Britton one of the most interesting and remarkable women of her time.

As members of what was then called the Torrey Botanical Club and still exists as the Torrey Botanical Society, both Elizabeth Gertrude and Nathaniel Lord Britton worked very hard to build what we have today. A world leader in botanical science that has grown to become a Garden on a mission.

The Botanical Garden’s International Plant Science Center is a world leader in plant research and exploration, using cutting-edge tools to discover, document, interpret, and preserve Earth’s vast botanical biodiversity. Garden scientists describe and name close to 50 new species each year in a race to catalog the world’s plant diversity before it is lost to deforestation and degradation of natural habitats. The Garden is one of the few institutions worldwide with the resources, collections, and expertise to develop the information needed to understand plant evolutionary relationships and manage plant diversity. It also serves as a center for scientific scholarship and as a sponsor of vital field work.

The Center employs an expert staff of professional researchers, technicians, and assistants, including dozens of Ph.D. scientists and candidates, in the fields of plant systematics, economic botany, ecology, molecular systematics, and plant genomics. The Center’s research facilities were greatly improved with the opening in May 2006 of the 28,000-square-foot, state-of-the-art Pfizer Plant Research Laboratory. It houses the Lewis B. and Dorothy Cullman Program for Molecular Systematics, Genomics Program, and Graduate Studies Program.

Garden scientists have been conducting international research for more than a century; this longstanding tradition in the field and in the laboratory is enhanced by peerless resources. The William and Lynda Steere Herbarium, the fourth largest in the world and the largest in the Western Hemisphere, houses 7.3 million specimens, from every continent and dating from the 18th century to the present. The C.V. Starr Virtual Herbarium provides Internet access to information for more than 1 million specimens in the Steere Herbarium, with thousands of new records being added each year. The LuEsther T. Mertz Library holds more than 1 million items spanning 10 centuries. The New York Botanical Garden Press is one of the largest science publication programs of any botanical garden, publishing journals, monographs, and books on botanical research.

The Garden’s Graduate Studies Program, the largest at any botanical garden in the world, was established in 1896 and addresses the shortage of biological scientists; 260 degrees have been granted, including 180 Ph.D.s. The program has grown to include six premier universities (CUNY, Columbia, Cornell, Fordham, New York University, and Yale), enrolling an annual average of 40 students during recent years. It has also built a network of graduates in key positions at institutions and universities around the world.

Many years have passed since these accomplishments began building on a rich tradition of science similar to the grant oriented research departments of universities and hospitals where a public-private partnership of support is employed. But the NYBG is based at a living museum and soon after a similar partnership began at the next door neighbor to the NYBG, where the Wildlife Conservation Society was formed. According to that booklet Scientific Research at the New York Botanical Garden (pdf.) the annual expense budget between private and public donations for science, has grown to $15 million in 2009.

This is a tradition that played a part in the U.S.A. becoming a scientific nation but now something is very wrong. Of course there is an economic downturn and austerity is the word that dominates politics today but there are other forces working against the scientific future of America. Where science is concerned much has changed in the cultural priorities between the early days of the NYBG, a time when the Panama Canal was in the nation’s future and this information age when elected officials openly discuss NASA as being a waste of money.

In this age when academic science has advance so much and political science has descended into corporate representation there is a very confusing message coming out of Washington. Certainly elected officials claiming that the educational value of PBS is not worthy of government spending and the false claim that scientific “climate studies” are coming from some sort of ecological activist does not inspire the next generation to want to become scientifically literate.

The negative effect of politicians going on cable news to either say that scientist are making up stories because of some “liberal political agenda” or claiming scientific evidence is inconclusive because conclusive scientific evidence would effect the bottom line of a corporate agenda must relate to a downturn in both scientific knowledge and support for increasing that knowledge.

Well not all politicians are negative, first lady Michelle Obama recently presented the 2010 National Medal for Museum and Library Services to The New York Botanical Garden in recognition of the excellent work going on in the garden.

“While some of your work may be national in scope,” the first lady said in her opening remarks, “ultimately your most powerful impact is local … And that’s particularly true in times of challenge and crisis, when many of you offer vital services, stepping up to be there for folks when they need you most. For example, The New York Botanical Garden started the Bronx Green-Up revitalization program, and they helped plant hundreds of school and community gardens in struggling neighborhoods so that families could grow their own fresh produce.”

The Garden was cited for both Bronx Green-Up, and for the Garden’s international plant research and conservation efforts dedicated to the study and understanding of the relationships between people and plants. “This award is a tribute to our dedicated staff members who continue to pursue the Garden’s mission in horticulture, science, education, and community service,” said Gregory Long.

“You come here from every corner of the country,” said the first lady,” from big cities and from small towns … But you’re here today because you all share the same commitment to excellence, the same determination to serve your communities.” Mrs. Obama continued, “Your work has never just been limited to the four walls of your institutions. Instead, you bring what you have to offer to as many people as possible, reaching out to undeserved populations, finding creative ways to stretch your resources as far as they can go.”

As a resident of Bronx County I can testify to the local efforts in public education. Bronx Green-Up dates back to my youth with the efforts to clean up the Bronx River and Plant-A-Tree. I wrote about one of the newer education projects, the marriage of and established institution and locavores in Got a Happy Story? DK GreenRoots Edition. From the Children’s Gardening Program to extensive support for adults trying to start and maintain community gardens and strong support for farmer’s markets, there are also amazing cultural exchanges like Kiku. You don’t need to be a New Yorker to love the NYBG, from anywhere you can get plant tips at Ask The Experts or go on an educational virtual tour of my favorite glass house, the Enid A. Haupt Conservatory.

The scientific efforts are local and can be as close to home as interactions with Bronx Botanicas and Bodegas but the lecture “Briefings From the Field: The Frontiers of Plant Discovery and Conservation” kicked off in the coastal rain forest of Brazil. The work of the Institute for Economic Botany that reaches out to so many from the Bronx includes but is not limited to;

• Food Security and Conservation of Crop Diversity: working to understand the biological, social, and political processes that lead to the maintenance, conservation, and continued evolution of major crop plants such as rice and lesser known food species.

• Sustainable Forest Management for Conservation and Economic Development: working with local communities to promote the sustainable exploitation of wild populations of economically important plants. Ultimately this will promote community resource management as an effective strategy for conserving natural habitats, such as tropical forests.

• Biodiversity and Human Health: working with traditional healers to record information about the uses of medicinal plants for the provision of primary health care, and training today’s health care professionals who treat patients using medicinal plants.

• Conservation of Biodiversity and Cultural Knowledge: working to record information on plant diversity, utilization, and traditional resource management, and partnering with local conservation agencies to use this knowledge to identify and protect key habitats.

At this year’s lecture the first speaker to talk about field studies was Dr. Wayt Thomas. After an introduction Gregory Long and an overview from Dr. James S. Miller, Wayt Thomas talked enthusiastically about his studies in the extremely threatened coastal forest of northeastern Brazil. The southern Bahia section of this area where the Botanical Garden has been running an active research and conservation program since 1990 is an area that is about twice the size of Switzerland and where forest have been reduced to fragments occupying less than 7% of their original extent.

In his work as a part of that DNA data bank of all the world’s trees the research of Wayt Thomas included setting aside one hectare (1.5 acre) of lowland tropical rain forest. In that study area there were 2500 trees, 230 species and 13 were new to science. Amazing biodiversity compared with a forest in the northeastern United States where there would be 7 to 9 species of trees, biological richness that once harmed, can never be replaced.

Going back to the lecture I attended twenty-four years ago, it seemed like the hands of the scientist were tied back then but now along with the scientific advances there is also a story of political progress in far away lands. The progress could be found in the story of the interactions in the field. After presenting the importance of this biodiversity, Wayt Thomas showed a slide of what occupies his area of study today. That area of Itacaré has become an eco-adventure resort where the main attraction is a protected Atlantic rain forest reserve. Wayt Thomas did not take credit for the move to ecotourism but Gregory Long’s introduction mention of Bronx trained scientist populating South America came to mind. What he did take credit for was the planning of the road to the resort. Originally planned to cut a straight line through and further segment the remaining forests, he worked with government and investors to create a road that fit in with the natural contours of the land and streams.

The following speaker was Andrew J. Henderson who discussed not his studies in the western hemisphere but NYBG research in far off Vietnam. The curator of the Institute of Systematic Botany and real Bronx neighborhood sort of guy who is one of the authors to Field Guide to the Palms of the Americas is also the author of Palms of Southern Asia. Prior to the previous ten years when Botanical Garden botanists began visiting Vietnam regularly, there had been little botanical exploration in this country since French colonial times.

“Vietnam has exceptional biological diversity, many of the species are found nowhere else, and a significant percentage of them are endangered, said Dr. Miller. “Decades of war have impeded their study, so we know very little about Vietnam’s rich botanical resources.”

Some of Andrew J. Henderson’s work is about economics, botany is often about balancing economics. Mr. Henderson has been working to understand a palm of economic importance to the Vietnamese, the rattans. At first I thought I heard him say that he introduced the rattan palms to western science. Amazed to hear that we had so little knowledge in western science about a plant we have been sitting on for generations but in fact there are several species of these spiny palms that rattan furniture is made from and he had “discovered an incredible 13 new species of rattan in Vietnam” while clarifying the scientific identities of already familiar rattans.

As part of his work and sponsored by the Vietnamese government, since these palms are becoming rare close to urban centers, Andrew J. Henderson is also seeking means of creating sustainable farming of these palms. For economic development they are starting rattan furniture and “la non” hat farms. There is a huge payoff in in this sort of exchange, something that reads like an international treaty to “manage biological diversity in Vietnam and conduct research to support sustainable management of useful plant species.”

The third speaker was Fabian A. Michelangeli who was there to talk about Cuba. All three speaker were animated and interesting but Fabian A. Michelangeli sounded like the Neil deGrasse Tyson of systematic botany. He was the one who took all the new scientific advantages of today and made it sound so exciting. His descriptions didn’t sound like dry laboratory experiments but exciting adventures into the unknown with a whole new set of toys. Makes sense since he has studied the meadow beauties of the world extensively, well really the Melastomataceae.

Fabian A. Michelangeli described Cuba much like it was presented in the PBS Series Nature last year, The Accidental Eden. The Caribbean is home to some 11,000 species of seed plants and nearly 72% of those plants occur nowhere else. With 75% of the Caribbean’s pre-Colombian forest already lost the lack of Cuban economic development over the past fifty years is like a limited offer to scientific study. Part of Fabian A. Michelangeli’s studies in the rich biodiversity of Cuba is choosing which of theses forest that also hold much mineral richness will be clear cut as Cuba develops. That sounds like a terrible story and a tough decision to make but the Cuban people need the income from the minerals and the opening of the Cuban economy is happening. Through an NYBG project called Habitat Specificity of Selected Endemic Cuban Plants the Cuban government is hoping to avoid the mistakes made by Caribbean islands that developed earlier.

I don’t mean to imply that the lecture was a matter of ignoring the desperate situation our planet is facing, far from it. Listening to these stories, none of them were presented as really good news. They represent solutions to problems through science. Humankind was given due credit for driving the biggest mass extinction since the dinosaurs. Global warming was mentioned as fact, destruction of habitat was painted in graphic detail and invasive species was given more credit than I’d ever thought about before.

As you would expect the “human incentive” for preservation was presented. It does seem necessary in these times to explain conservation in terms of losing money. Much like the way the UN launched 2010 as the Year of Biodiversity, more than once I heard “Biological Diversity is Natural Capital.” For years I’ve heard about the mysteries of medicinal plants we might never discover because of habitat destruction. I remember hearing twenty-four years back “We have only explored three percent of the plant species as cures for disease” and this year it was explained to be misleading. In fact we have only explored three percent as a cure for a few specific diseases. James S. Miller said “it is absurd” to believe that we understand the pharmaceutical value of even three percent of the plant kingdom.

Listening to this lecture, I couldn’t help but think about what I hear from elected officials about science. I sounded great to hear about progressive work, environmental efforts and some science facts for a change.

There was on very disturbing story and it was not about scientific knowledge but something that scientist don’t quite understand. Fabian A. Michelangeli who had me cheering for understanding evolution and booing threats to biological diversity presented both evolution and biodiversity in layman’s terms by comparing it with orchid enthusiasts using hybrids to make the prefect orchid. In the world of plants, just like male donkey and a female horse makes a mule, this happens all the time but every now and then the offspring is fertile and there is a new plant species in the world. As we walk in a forest species vary from tree ferns that date back 200 million years to plants that have only existed for a few hundred years. Somewhere in the world today there might even be a plant species that has only existed for a day. Fabian A. Michelangeli explained that while wiping out twenty-five percent of the plant species will greatly hinder biodiversity, scientist can’t say for sure but plant evolution might just end. What they do know for sure is that we are on the verge of a mass extinction, that between the threats to biodiversity from invasive plants and losing 100,000 species, the human race could actually be on the verge of ending vascular plant evolution on planet earth.

I should mention that these are my opinions based on what I heard. It is actually a brief look at the good work being done by the New York Botanical Garden. For a more extensive look that is written by professionals, the booklet Scientific Research at the New York Botanical Garden (pdf.) is a great read about ecological progress. The first words are…

The New York Botanical Garden is an advocate for the plant kingdom…

After reading it, you might think the NYBG is worthy of a donation.

Of course the creation of

Of course the creation of  Besides her work in making the NYBG a possible Elizabeth Britton was also one of 25 founding members of the Botanical Society of America and launched several public efforts to preserve wildflowers including being the founder of the

Besides her work in making the NYBG a possible Elizabeth Britton was also one of 25 founding members of the Botanical Society of America and launched several public efforts to preserve wildflowers including being the founder of the

Recent Comments