The Confidence Fairy is Dead but its ghost is still haunting the halls of the European Union countries and the United States, as Herr Doktor notes:

This was the month the confidence fairy died.

For the past two years most policy makers in Europe and many politicians and pundits in America have been in thrall to a destructive economic doctrine. [..]

The good news is that many influential people are finally admitting that the confidence fairy was a myth. The bad news is that despite this admission there seems to be little prospect of a near-term course change either in Europe or here in America, where we never fully embraced the doctrine, but have, nonetheless, had de facto austerity in the form of huge spending and employment cuts at the state and local level.

Krugman also pointed the de facto austerity policy of the Obama administration and Congress have added to the stagnant job market:

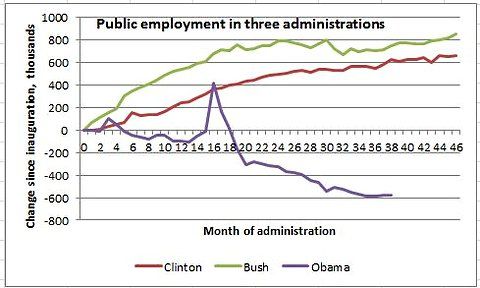

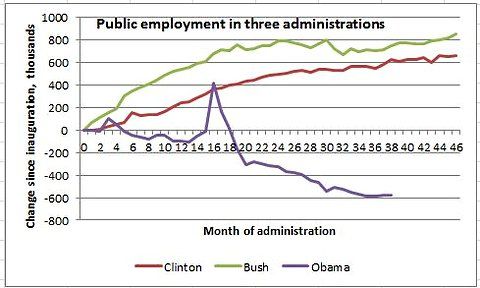

Here’s a comparison of changes in government employment (federal, state, and local) during the first four years of three presidents who came to office amid a troubled economy:

That spike early on is Census hiring; [..] If public employment had grown the way it did under Bush, we’d have 1.3 million more government workers, and probably an unemployment rate of 7 percent or less.

The job market is taking its toll on consumer spending which will continue to slow down any recovery:

More Americans than forecast filed applications for unemployment benefits last week and consumer confidence declined by the most in a year, signaling that a cooling labor market may restrain household spending. [..]

“There has been some slowdown in the labor market,” said Yelena Shulyatyeva, a U.S. economist at BNP Paribas in New York, who correctly projected the level of jobless claims. “That makes consumers feel less confident, and makes them more cautious about their spending. We could see some weakness in April payrolls.”

And even though the predictions about the housing market have been optimistic don’t be fooled, there is a dark side as falling home prices drag new buyers under water

More than 1 million Americans who have taken out mortgages in the past two years now owe more on their loans than their homes are worth, and Federal Housing Administration loans that require only a tiny down payment are partly to blame.

That figure, provided to Reuters by tracking firm CoreLogic, represents about one out of 10 home loans made during that period.

It is a sobering indication the U.S. housing market remains deeply troubled, with home values still falling in many parts of the country, and raises the question of whether low-down payment loans backed by the FHA are putting another generation of buyers at risk.

As of December 2011, the latest figures available, 31 percent of the U.S. home loans that were in negative equity – in which the outstanding loan balance exceeds the value of the home – were FHA-insured mortgages, according to CoreLogic.

In an interview with The European Nobel Prize winning economist, Joseph Stiglitz said:

…When you look at America, you have to concede that we have failed. Most Americans today are worse off than they were fifteen years ago. A full-time worker in the US is worse off today than he or she was 44 years ago. That is astounding – half a century of stagnation. The economic system is not delivering. It does not matter whether a few people at the top benefitted tremendously – when the majority of citizens are not better off, the economic system is not working… [..]

The argument that the response to the current crisis has to be a lessening of social protection is really an argument by the 1% to say: “We have to grab a bigger share of the pie.” But if the majority of people don’t benefit from the economic pie, the system is a failure. I don’t want to talk about GDP anymore, I want to talk about what is happening to most citizens.

Meanwhile back in Europe with the distinct possibility that French President Nicholas Sarkozy may lose to the Socialist candidate François Hollande, some leaders are getting the message but aren’t ready to give up totally:

Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte and Finance Minister Jan Kees de Jager struck a deal with the opposition and got a majority backing on an austerity package to meet the 3 percent budget deficit target in 2013, after seven weeks of talks with Geert Wilders’s Freedom Party failed and led to the collapse of the minority government.

The package increases the value-added tax to 21 percent from 19 percent, doubles the bank tax to 600 million euros ($791 million) and changes the financing of mortgages, De Jager said in a letter to parliament yesterday.[..]

The Labor Party, the Socialist Party as well as the Freedom Party of Geert Wilders didn’t back the agreement. “This is a bad package and the people with a state pension will pay the bill,” Wilders said in parliament.

In an editorial in Bloomberg News, the editors expressed their ideas how European leaders can “boost economic growth in the euro area”:

First, Europe’s leaders must recognize that common deficit rules alone will not guarantee the currency union’s survival. When countries such as Italy and Spain fall into a spiral of shrinking output and rising budget deficits, countries with stronger economies must be willing to help, either by transferring funds or by stimulating their own demand.

Currently, that would mean more German spending. [..] The Bundesbank would also need to live with a little more German inflation than the current 2.1 percent. Higher prices in Germany would help make other euro- area economies and their exports more competitive, reducing both their current account deficits and Germany’s surplus.

Second, the agreement should give Spain and Greece in particular more time to bring down debts piled up over the past 30 years. Requiring them to slash education, research and development, and other budgets will only stunt their future growth potential. To calm markets concerned about Spain’s deficits, the rest of Europe — Germany again — and the International Monetary Fund would have to provide more bailout funds.

Finally, the pact should acknowledge one of the most immediate requirements for a return to economic expansion: Recapitalization of private sector banks so that they can start providing businesses with more credit. Without that, Europe is doomed to anemic growth and a persistent confidence crisis, no matter what documents its politicians may sign.

Stiglitz in his interview makes two important points. First, “The question of social protection does not have to do with the structure of production”

It has to do with social cohesion or solidarity. That is why I am also very critical of Draghi’s argument at the European Central Bank that social protection has to be undone. There are no grounds upon which to base that argument. The countries that are doing very well in Europe are the Scandinavian countries. Denmark is different from Sweden, Sweden is different from Norway – but they all have strong social protection and they are all growing.

Hear that, Mr President and Congress? Get your hands off reduction in the social safety net.

And second, that here in the US, “politics is at the root of the problem“:

Most Americans understand that fraud political processes play in fraud outcomes. But we don’t know how to break into that system. Our Supreme Court was appointed by moneyed interests and – not surprisingly – concluded that moneyed interests had unrestricted influence on politics. In the short run, we are exacerbating the influence of money, with negative consequences for the economy and for society. [..]

The diagnosis is that politics is at the root of the problem: That is where the rules of the game are made, that is where we decide on policies that favor the rich and that have allowed the financial sector to amass vast economic and political power. The first step has to be political reform: Change campaign finance laws. Make it easier for people to vote – in Australia, they even have compulsory voting. Address the problem of gerrymandering. Gerrymandering makes it so that your vote doesn’t count. If it does not count, you are leaving it to moneyed interests to push their own agenda. Change the filibuster, which turned from a barely used congressional tactic into a regular feature of politics. It disempowers Americans. Even if you have a majority vote, you cannot win.

The Europeans may well be the “game changers” because the election of their politicians doesn’t hinge on campaign contributions, long drawn out primaries or a rigid two party system that has degenerated into a lack of political choice. We need to kill the fairy once and for all and put governance in the hands of the American people.

Recent Comments