I wish.

Japan the Model

By PAUL KRUGMAN, The New York Times

Published: May 23, 2013

A generation ago, Japan was widely admired – and feared – as an economic paragon. Business best sellers put samurai warriors on their covers, promising to teach you the secrets of Japanese management; thrillers by the likes of Michael Crichton portrayed Japanese corporations as unstoppable juggernauts rapidly consolidating their domination of world markets.

Then Japan fell into a seemingly endless slump, and most of the world lost interest. The main exceptions were a relative handful of economists, a group that happened to include Ben Bernanke, now the chairman of the Federal Reserve, and yours truly. These Japan-obsessed economists viewed the island nation’s economic troubles, not as a demonstration of Japanese incompetence, but as an omen for all of us. If one big, wealthy, politically stable country could stumble so badly, they wondered, couldn’t much the same thing happen to other such countries?

Sure enough, it both could and did. These days we are, in economic terms, all Japanese – which is why the ongoing economic experiment in the country that started it all is so important, not just for Japan, but for the world.

…

It would be easy for Japanese officials to make the same excuses for inaction that we hear all around the North Atlantic: they are hamstrung by a rapidly aging population; the economy is weighed down by structural problems (and Japan’s structural problems, especially its discrimination against women, are legendary); debt is too high (far higher, as a share of the economy, than that of Greece). And in the past, Japanese officials have, indeed, been very fond of making such excuses.

The truth, however – a truth that the Abe government apparently gets – is that all of these problems are made worse by economic stagnation. A short-term boost to growth won’t cure all of Japan’s ills, but, if it can be achieved, it can be the first step toward a much brighter future.

Land of the Rising Sums

By PAUL KRUGMAN, The New York Times

May 10, 2013, 8:58 am

The good news for Abenomics keeps rolling in; of course, it’s not over until the sumo wrestler sings, but there has clearly been a major change in Japanese psychology and expectations, which is what it’s all about.

Why does this seem to be working as well as it is? Long ago I argued that to gain traction in a liquidity trap, the central bank needed to credibly promise to be irresponsible – that is, convince investors that it would not rein in monetary expansion once the economy was at full employment and inflation was starting to rise. And this is a hard thing to do; no matter what central bankers may say, history shows that they often revert to type at the first opportunity. The examples of successful changes in expectations tend to involve drastic regime changes, like FDR taking us off the gold standard.

Monetary Policy In A Liquidity Trap

By PAUL KRUGMAN, The New York Times

April 11, 2013, 7:22 am

I’ve made it clear that I very much approve of Japan’s new monetary aggressiveness. But I gather that some readers are confused – haven’t I been arguing that monetary policy is ineffective in a liquidity trap? The brief answer is that current policy is ineffective, but that you can still get traction if you can change investors’ beliefs about expected future monetary policy – which was the moral of my original Japan paper, lo these 15 years ago. But I thought it might be worthwhile to go over this again.

So, at this point America and Japan (and core Europe) are all in liquidity traps: private demand is so weak that even at a zero short-term interest rate spending falls far short of what would be needed for full employment. And interest rates can’t go below zero (except trivially for very short periods), because investors always have the option of simply holding cash.

…

Under these circumstances, normal monetary policy, which takes the form of open-market operations in which the central bank buys short-term debt with money it creates out of thin air, have no effect. Why?

Well, the reason open-market operations usually work is that people are making a tradeoff between yield and liquidity – they hold money, which offers no interest, for the liquidity but limit their holdings because they pay a price in lost earnings. So if the central bank puts more money out there, people are holding more than they want, try to offload it, and drive rates down in the process.

But if rates are zero, there is no cost to liquidity, and people are basically saturated with it; at the margin, they’re holding money simply as a store of value, essentially equivalent to short-term debt. And a central bank operation that swaps money for debt basically changes nothing. Ordinary monetary policy is ineffective.

…

Here’s the thing, however: the economy won’t always be in a liquidity trap, or at least it might not always be there. And while investors shouldn’t care about what the central bank does now, they should care about what it will do in the future. If investors believe that the central bank will keep the pedal to the metal even as the economy begins to recover, this will imply higher inflation than if it hikes rates at the first hint of good news – and higher expected inflation means a lower real interest rate, and therefore a stronger economy.

So the central bank can still get traction if it can change expectations about future policy.

The trouble is that central bankers have a credibility problem – one that’s the opposite of the traditional concern that they might print too much money. Instead, the concern is that at the first sign of good news they’ll revert to type, snatching away the punch bowl. You can see in the figure above that the Bank of Japan did just that in the 2000s.

The hope now is that things have changed enough at the Bank of Japan that this time it can, as I put it all those years ago, “credibly promise to be irresponsible”.

And that’s why I’m bullish on the Japanese experiment, even though current monetary policy has little effect.

I’m sure my many, many MMT friends will be happy to point out how wrong the theoretical basis for this analysis is, but I’ve always been a pragmatic centrist- ask Armando; and as long as our policy dogs hunt in the same direction, who cares?

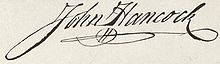

On this day in 1775,

On this day in 1775,  Hancock was president of Congress when the

Hancock was president of Congress when the

Recent Comments