(2 PM – promoted by TheMomCat)

The Steel Interstate is a proposal to pursue dramatic gains in the energy efficiency of long haul freight transport in the United States, resulting in:

The Steel Interstate is a proposal to pursue dramatic gains in the energy efficiency of long haul freight transport in the United States, resulting in:

- Substantial reductions in Petroleum Imports;

- Substantial reductions in Greenhouse Gas emissions;

- Substantially improved protection from Petroleum Supply interruptions;

- Improved productivity for North American manufacturing; and

- Substantial reductions in damage to the existing Asphalt Interstate System

How can it promise all of this? By mining gross inefficiency. The United States has one of the most energy inefficient systems of moving freight long distances available under current technology, and we combine that with an economy that relies heavily on moving freight long distances.

Some of the specific sources of energy efficiency are:

- Moving cargoes in linked electric freight trains offers less air resistance than moving cargoes in individual trucks, because the freight car ahead provides a slipstream for the freight car immediately behind;

- Steel wheel on steel rail has less rolling resistance than rubber tire on asphalt road;

- Electric motors are more efficient than diesel or gasoline internal combustion engines; and

- When braking, electric trains can put a load on their electric motors and generate power, feeding it back onto the line

Overall, long haul electric freight is around 15 times more energy efficient than long haul diesel semi freight. I tend to express this as over ten times the energy efficiency, to allow leeway for possibly longer routings when taking advantage of the Steel Interstate.

Long haul electric freight trains are also more space efficient than long haul truck transport. Freight demands that would require multiple lanes each way just for truck traffic can be readily accommodated on a two track mainline route. This can be done while accommodating a mix of 60mph heavy freight and 100mph fast container freight by including regular extended sections of passing track: the difference between passing track and sidings is that on-schedule faster and slower trains using the passing track remain in motion, rather than one sitting still in a siding waiting for the other to pass.

Finally, the operating cost per ton-mile for electric freight for both 60mph heavy freight and 90mph fast freight is enough lower than the operating cost of long haul trucking that the government can fund a National Steel Interstate with interest subsidies alone, with Access Fees and User Fees refunding the original capital cost of the system ~ initially, funding expansion of the system, and finally funding retiring the bonds.

If Its Such A Great Idea, Why Don’t We Have Steel Interstates Yet?

So, if there are so many substantial reasons for pursuing Steel Interstates, why aren’t we doing it yet?

Part of the issue was expressed by the Machiavelli:

And it ought to be remembered that there is nothing more difficult to take in hand, more perilous to conduct, or more uncertain in its success, than to take the lead in the introduction of a new order of things. Because the innovator has for enemies all those who have done well under the old conditions, and lukewarm defenders in those who may do well under the new. This coolness arises partly from fear of the opponents, who have the laws on their side, and partly from the incredulity of men, who do not readily believe in new things until they have had a long experience of them. Thus it happens that whenever those who are hostile have the opportunity to attack they do it like partisans, whilst the others defend lukewarmly,

We have a whole tapestry of formal and informal institutions that are adapted to our current freight transport system, since they were developed as part of the process of solving problems that arose in running that transport system. And because Economic Institutions encapsulate previously arrived at solutions to previously experienced problems, and in many cases have been confirmed in whole or part by appeal to sovereign authority, Economic Institutions are normally backward looking.

This is a problem that faces all innovation. There is a further particular problem with long haul electric freight transport: even getting a “pilot project” underway requires a substantial amount of funding. “Long haul” cannot be demonstrated in a 10 or 100 mile long corridor. The RAILSolutions “pilot project” is from Harrisburg, PA to Memphis, TN, via Huntsville, AL; Chattanooga, TN; Knoxville, TN; Bristol, TN; Roanoke, VA; and Hagerstown, MD. Not only does Harrisburg, PA offer rail connections throughout the Northeast, it also offers an electrified corridor through to Philadelphia via the electrified Keystone East corridor.

This is a problem that faces all innovation. There is a further particular problem with long haul electric freight transport: even getting a “pilot project” underway requires a substantial amount of funding. “Long haul” cannot be demonstrated in a 10 or 100 mile long corridor. The RAILSolutions “pilot project” is from Harrisburg, PA to Memphis, TN, via Huntsville, AL; Chattanooga, TN; Knoxville, TN; Bristol, TN; Roanoke, VA; and Hagerstown, MD. Not only does Harrisburg, PA offer rail connections throughout the Northeast, it also offers an electrified corridor through to Philadelphia via the electrified Keystone East corridor.

That “pilot project” is about 1,000 miles of corridor.

That is both very long, and quite short. Quite short since a fully elaborated Steel Interstate System, as proposed by Alan Drake with support from modelling by the Millennium Institute would be 36,000 miles. So a single 1,000 mile long corridor is only demonstrating a part of the available transport benefits from a Steel Interstate system. Indeed, as the longer the haul, the greater the benefit in shifting freight from truck to long haul electric rail, there are likely to be entire transport markets that are not captured on a 1,000 mile corridor that will find a 2,000-3,000 mile corridor a compelling option.

If we project from the estimated $500b cost of fully built 36,000 miles of electrified rail, including 60mph heavy freight, 90mph fast freight, and grid-grid Electricity Superhighway HVDC transmission along the Steel Interstate corridors, that is $14m per mile, so 1,000 miles is $14b. Now, $14b may not seem like much set against the size of the Defense Budget. Indeed, $14b isn’t a tremendous amount when we consider the $80b required annually to preserve our current $1.72T Asphalt Interstate System, or the $160b annually required to bring our national highway system to a state of good repair.

However, $14b is far more than we are used to spending on “pilot projects”.

There is also an efficiency in building a large system on an ongoing basis, as proposed by Alan Drake. Suppose that a specific work team can complete 50 miles of corridor annually. 10 teams could complete a 1,000 mile corridor in a couple of years. However, then the start-up and establishment costs of the teams are only spread over two years. However, if that 1,000 mile corridor was one of a number of funded corridors, when those ten work teams were finished on the initial 1,000 mile corridor, they could move on to another 1,000 mile corridor.

Indeed, since there will be learning by doing in the process of building the corridors, the process of building the Steel Interstate should become more efficient over the course of the project.

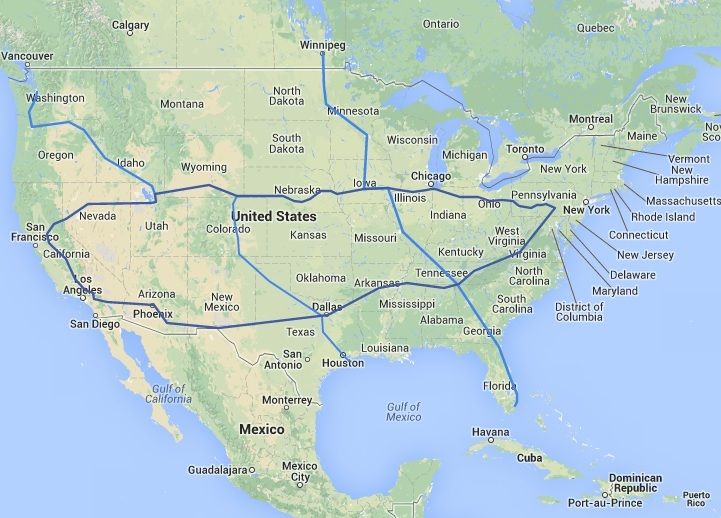

So for this reason, while I fully support the corridor set out as an initial corridor by RAILSolutions, I propose a push to roll out a national network:

- Harrisburg, PA to Memphis, TN, via Roanoke VA & Hunstville, AL;

- Memphis, TN to El Paso, TX, via Little Rock, AR and Dallas, TX;

- El Paso, TX to Riverside, CA, via Tuscon and Pheonix, AZ;

- RIverside, CA to Reno, NV, via Fresno and Sacramento CA;

- Reno Nevada to Ogden Utah via Salt Lake City, Utah.

- Harrisburg PA to Chicago, IL, via Pittsburgh PA and Fort Wayne, IN;

- Chicago, IL to Ogden, UT, via Des Moines, IA and Cheyenne, WY;

- Ogden UT to Seattle, WA via Boise, ID and Portland, Oregon

- Miami, FL to Saint Louis, MO via Atlanta, Georgia and Nashville, Tennessee;

- Saint Louis, MO to Fargo, ND via Des Moines, IA and Minneapois/St Paul, MN;

- with potential connection to the Canadian rail system at Winnipeg.

- Houston, TX to Cheyenne, Wyoming via Dallas, TX, Lubbock, TX, and Denver, Colorado.

This is 8,000-10,000 miles (specific mileage will depend upon specific alignment decisions made by the planning authority within the planning criteria set out in the funding authority). However, I am splitting it into three parts:

- The Liberty Line from Harrisburg PA through to California on the southern route, then through Reno to Salt Lake City and Ogden, Utah

- The National Line from Harrisburg PA through to Seattle, Washington, via the Chicago freight bypass and Rock Island route to Ogden Utah;

- The National Connector Lines, cutting across the main transcontinental loop from Miami through St. Louis to Minneapolis, MN and Fargo, ND, and Houston through Lubbock, TX and Denver, Colorado to Cheyenne, Wyoming.

The Liberty and National lines are being financed by ongoing direct interest subsidy, and then the National Connector Lines financed by Revenue Bonds on Access Fees and User Fees collected on the system. When Access and User Fees collected on the system begin to exceed the finance service requirements of the Revenue Bonds, the surplus is devoted to first retiring the Revenue Bonds, and then retiring the original subsidized interest bonds.

Assuming one year for detailed project engineering and approvals on initial segments, and establishing ten work teams per year to complete 50 miles of corridor annually, the interest-subsidized portion might proceed (note that the progress points are rough approximations):

- Year 1: initial project planning, alignment agreements, approvals and detailed engineering;

- Year 2: Begin Corridor 1 from Harrisburg to Memphis, with 10 work teams;

- Year 3: Continue Corridor 1 to Memphis, Begin Corridor 2 from Harrisburg to Chicago, 20 work teams;

- Year 4: Continue Corridor 1 to Dallas, TX, Continue Corridor 2 to Omaha, NE, 20 work teams;

- Year 5: Continue Corridor 1 to El Paso, TX, Continue Corridor 2 to Ogden, UT, 20 work teams;

- Year 6: Continue Corridor 1 to Phoenix, AZ, Complete Corridor 2 to Seattle, WA, 20 work teams;

- Year 7: Continue Corridor 1 to Sacramento, CA, 20 work teams.

- Year 8: Complete Corridor 1, to Ogden Utah, 10 work teams.

Which in terms of spending at an assumed $20m per mile (since Federal Finance is typically in nominal terms rather than so-called “real” costs corrected for inflation) is:

- Year 1: Initial project planning funding, about $500m

- Year 2: 500 miles, 10 works teams, $10b;

- Year 3-7: 1,000 miles, 20 works teams, $20b annually;

- Year 8: 500 miles, 10 work teams, $10b

- Totals: 6,000 miles, $120b capital cost

At a borrowing rate of 5% for Energy Independence Bonds (structured as Fixed Interest Payment Consol Bonds to set them beyond the reach of political sabotage of Treasury’s capacity to sell debt by playing games with the debt ceiling), that requires an interest subsidy of $500m in year 2, then an additional $1b a year in years 3-7, arriving at $6b annually by Year 8.

Why is $14b Once More than $6b Annually in Eight Years Time?

The hard work in gaining this interest subsidy is not coming up with one or another Pay As You Go spending or tax subsidy offsets, or one or multiple dedicated tax funding streams.

The hard work in gaining this interest subsidy is not coming up with one or another Pay As You Go spending or tax subsidy offsets, or one or multiple dedicated tax funding streams.

The hard work is building a coalition of support.

We can look to mobilize support from a “Green Jobs” coalition of supporters of action on Climate Change, supporters of reducing the wear and tear on our Asphalt Interstates, Rail workers unions, and businesses who stand to gain contracts as equipment, parts and materials suppliers for a broad national effort.

However, to have the best prospects of success, it is likely that we have to look further than the Green Jobs coalition. The biggest single institutional supporter of deployment of sustainable, renewable energy sources in the United States at present is the Department of Defense. This should be no surprise, since there is entrenched political support for a scale of industrial planning inside the Military Industrial Complex that was fought against tooth and nail regarding the rest of our national economy … in many cases fought against ferociously by some of the very same firm supports of industrial planning by the Department of Defense.

And any large organization that takes a serious look at the strategic risks that are faced by the US economy will turn its attention to our dependence on imported energy. Much of our imported energy travels over long and vulnerable supply chains, and most of it consists of non-renewable resources that must be constantly supplemented by new discovery and exploitation simply to maintain a constant flow. The Steel Interstate offers an opportunity to provide long-haul freight transport at one-tenth the energy consumption, and using electricity which we can generate from a range of abundant domestic resources, which may be harvested with dispersed equipment which is, therefore, far more robust against the threat of sabotage than large nuclear or coal power plants.

However, the “Military-Industrial Complex” is more precisely named the “Military-Industrial-Congressional Complex”, and the Department of Defense is far more likely to push for a project such as this if there is the prospect of assembling a coalition of Senators prepared to support the project. That coalition of Senators can hold hearings on the “challenge” of the vulnerability of our military logistics to an interruption of petroleum supply and the value of a long haul electric freight rail system to addressing that challenge. That “pressure” provides leverage for those in the Department of Defense who take the problem seriously to bring the formidable propaganda resources of the Department of Defense to bear on popularizing the Steel Interstate.

And by now, I am sure that you will have noticed something about the Steel Interstate Map at the top of this week’s Sunday Train. The system passes directly through:

- Pennsylvania, Virginia, Tennessee, Alabama, Arkansas, Texas, Arizona, California, Nevada, Utah

- Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Iowa, Nebraska, Wyoming, Idaho, Oregon, Washington

- Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Missouri, Minnesota, North Dakota, Colorado.

… which is 26 states on its own, representing a mix of all-Democratic, all-Republican, and split D/R Senate delegations.

That mix of both parties is in a very basic sense guaranteed by any map arrived at in a process that focuses on meeting long haul freight needs. After all, if you lay out a national electric freight rail network, following the highest volume long haul truck freight lines of traffic, it will necessarily connect with the large metropolitan centers that generate Democratic election victories. Along the way it will necessarily pass through many miles of rural and outer suburban areas that generate Republican election victories.

Further, the system also connects into the electrified Northeast Corridor, with primary available capacity late at night, which is precisely the most strategic time for providing freight origins from and arrivals to local freight dispatch centers in urban areas, and by its nature, it also serves any states that can connect to it via short distance truck and rail freight. In practice, it offers direct benefits to all 48 contiguous States.

So, if the Military Industrial Complex can be brought on board in the coalition to establish the initial 8,000-10,000 miles Steel Interstate system, then I believe that it shall be possible for the meat-grinder of US politics to come up with some system to permit the finance of the system.

Conversations, Considerations and Contemplations

Longer time readers of the Sunday Train will have known coming in that I advocate establishment of a Steel Interstate System … and now more recent Sunday Train readers have been introduce to the proposal.

However, as always, rather looking for some overarching conclusion, I now open the floor to the comments of those reading.

If you have an issue on some other area of sustainable transport or sustainable energy production, please feel free to start a new main comment. To avoid confusing me, given my tendency to filter comments through the topic of this week’s Sunday Train, feel free to use the shorthand “NT:” in the subject line when introducing this kind of new topic.

And if you have a topic in sustainable transport or energy that you want me to take a look at in the coming month, be sure to include that as well.

1 comments

Author