This is your morning Open Thread. Pour your favorite beverage and review the past and comment on the future.

Find the past “On This Day in History” here.

Click on images to enlarge

May 6 is the 126th day of the year (127th in leap years) in the Gregorian calendar. There are 239 days remaining until the end of the year.

On this day in 1994, English Channel tunnel opens.

In a ceremony presided over by England’s Queen Elizabeth II and French President François Mitterand, a rail tunnel under the English Channel was officially opened, connecting Britain and the European mainland for the first time since the Ice Age.

The channel tunnel, or “Chunnel,” connects Folkstone, England, with Sangatte, France, 31 miles away. The Chunnel cut travel time between England and France to a swift 35 minutes and eventually between London and Paris to two-and-a-half hours.

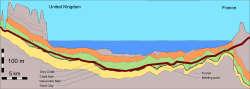

As the world’s longest undersea tunnel, the Chunnel runs under water for 23 miles, with an average depth of 150 feet below the seabed. Each day, about 30,000 people, 6,000 cars and 3,500 trucks journey through the Chunnel on passenger, shuttle and freight trains.

Millions of tons of earth were moved to build the two rail tunnels–one for northbound and one for southbound traffic–and one service tunnel. Fifteen thousand people were employed at the peak of construction. Ten people were killed during construction.

Proposals and attempts

In 1802, French mining engineer Albert Mathieu put forward a proposal to tunnel under the English Channel, with illumination from oil lamps, horse-drawn coaches, and an artificial island mid-Channel for changing horses.

In 1802, French mining engineer Albert Mathieu put forward a proposal to tunnel under the English Channel, with illumination from oil lamps, horse-drawn coaches, and an artificial island mid-Channel for changing horses.

In the 1830s, Frenchman Aimé Thomé de Gamond performed the first geological and hydrographical surveys on the Channel, between Calais and Dover. Thomé de Gamond explored several schemes and, in 1856, he presented a proposal to Napoleon III for a mined railway tunnel from Cap Gris-Nez to Eastwater Point with a port/airshaft on the Varne sandbank at a cost of 170 million francs, or less than £7 million.

In 1865, a deputation led by George Ward Hunt proposed the idea of a tunnel to the Chancellor of the Exchequer of the day, William Ewart Gladstone.

After 1867, William Low and Sir John Clarke Hawkshaw promoted ideas, but none were implemented. An official Anglo-French protocol was established in 1876 for a cross-Channel railway tunnel. In 1881, British railway entrepreneur Sir William Watkin and French Suez Canal contractor Alexandre Lavalley were in the Anglo-French Submarine Railway Company that conducted exploratory work on both sides of the Channel. On the English side a 2.13-metre (7 ft) diameter Beaumont-English boring machine dug a 1,893-metre (6,211 ft) pilot tunnel from Shakespeare Cliff. On the French side, a similar machine dug 1,669 m (5,476 ft) from Sangatte. The project was abandoned in May 1882, owing to British political and press campaigns advocating that a tunnel would compromise Britain’s national defences. These early works were encountered more than a century later during the TML project.

In 1919, during the Paris Peace Conference, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George repeatedly brought up the idea of a Channel tunnel as a way of reassuring France about British willingness to defend against another German attack. The French did not take the idea seriously and nothing came of Lloyd George’s proposal.

In 1955, defence arguments were accepted to be irrelevant because of the dominance of air power; thus, both the British and French governments supported technical and geological surveys. Construction work commenced on both sides of the Channel in 1974, a government-funded project using twin tunnels on either side of a service tunnel, with capability for car shuttle wagons. In January 1975, to the dismay of the French partners, the British government cancelled the project. The government had changed to the Labour Party and there was uncertainty about EEC membership, cost estimates had ballooned to 200% and the national economy was troubled. By this time the British Priestly tunnel boring machine was ready and the Ministry of Transport was able to do a 300 m (980 ft) experimental drive. This short tunnel would however be reused as the starting and access point for tunnelling operations from the British side.

In 1979, the “Mouse-hole Project” was suggested when the Conservatives came to power in Britain. The concept was a single-track rail tunnel with a service tunnel, but without shuttle terminals. The British government took no interest in funding the project, but Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher said she had no objection to a privately funded project. In 1981 British and French leaders Margaret Thatcher and François Mitterrand agreed to set up a working group to look into a privately funded project, and in April 1985 promoters were formally invited to submit scheme proposals. Four submissions were shortlisted:

In 1979, the “Mouse-hole Project” was suggested when the Conservatives came to power in Britain. The concept was a single-track rail tunnel with a service tunnel, but without shuttle terminals. The British government took no interest in funding the project, but Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher said she had no objection to a privately funded project. In 1981 British and French leaders Margaret Thatcher and François Mitterrand agreed to set up a working group to look into a privately funded project, and in April 1985 promoters were formally invited to submit scheme proposals. Four submissions were shortlisted:

a rail proposal based on the 1975 scheme presented by Channel Tunnel Group/France-Manche (CTG/F-M),

Eurobridge: a 4.5 km (2.8 mi) span suspension bridge with a roadway in an enclosed tube

Euroroute: a 21 km (13 mi) tunnel between artificial islands approached by bridges, and

Channel Expressway: large diameter road tunnels with mid-channel ventilation towers.

The cross-Channel ferry industry protested under the name “Flexilink”. In 1975 there was no campaign protesting against a fixed link, with one of the largest ferry operators (Sealink) being state-owned. Flexilink continued rousing opposition throughout 1986 and 1987. Public opinion strongly favoured a drive-through tunnel, but ventilation issues, concerns about accident management, and fear of driver mesmerisation led to the only shortlisted rail submission, CTG/F-M, being awarded the project.

We are going to be hearing increasingly this year about the Highway Funding Crisis. Much of that discussion will be directed toward exploiting the political leverage that our car addiction gives to the Highway Lobby.

We are going to be hearing increasingly this year about the Highway Funding Crisis. Much of that discussion will be directed toward exploiting the political leverage that our car addiction gives to the Highway Lobby.

Recent Comments