(4 pm. – promoted by ek hornbeck)

From the Sunday Train

There was a gleam of hope this week for state officials faced with the prospects of having to start delaying projects and lay off people working on maintenance and new construction funded from the Federal Highway Fund: Bloomberg:

There was a gleam of hope this week for state officials faced with the prospects of having to start delaying projects and lay off people working on maintenance and new construction funded from the Federal Highway Fund: Bloomberg:

Lawmakers’ fight over how to fund roads and transit probably will end with legislation from the Republican-led House sent to President Barack Obama, leadership aides in both parties said.

House and Senate leaders have been collaborating on a strategy for preventing the Highway Trust Fund from running dry at the height of the summer road-construction season. While bills approved July 10 by committees in both chambers are similar, the Democratic-led Senate’s version contains tax proposals seen as obstacles in the House.

But this is akin to lending someone with a broken leg crutches and hoping that it will heal on its own. For some fractures, that might work, but most would require a splint at least, and for serious fractures, you need to set the leg and put it in a cast of some sort.

In the case at hand, the long term broken funding model that lays behind the Highway Funding crisis is something that requires something better than a temporary loan of crutches.

So, what are the crutches being offered?

As is often the case, the Republican description of a Democratic Senate proposal makes it sound far more dramatic than it actually is. The Democratic Senate proposal includes measures to collect taxes that tax deadbeats currently owe that is anticipated to yield $340m/year on average, setting up a headline figure of “$3.4 billion*” {* Footnote: over ten years}, and an attack ad charge of a “$3.4b tax increase*” {* Footnote: in collections of taxes that it is anticipated that tax deadbeats will otherwise try to skip out on, over the coming ten years.}

The original Senate Chairman’s mark-up (pdf) include measures estimated to yield an average of $900m a year (which is, note, less than $3 per person per year). And what are the kinds of things that the GOP House wants to defend the country against?

- A change in the cap on Federal heavy truck annual use tax, regarding taxes they are owed by trucks too heavy to run on Interstate Highways under normal rules, but which may be allowed to run on state highways in some states, and under specific regulations applying to specific sections of some Interstates. This primarily makes it easier for states to collect state use taxes they are owed by operators of those heavy trucks, for an additional $135m/yr.

- Require mortgage interest information returns to include outstanding balance, address of the property, property taxes paid from escrow, and loan origination date. This would reduce tax cheating by recipients of the mortgage interest deduction, which is an annual $70b tax subsidy going primarily to high income households, with (as of 2012)more than 3/4 of the benefit received by households earning over $100,000, and over half of lower income homeowners receiving no benefit at all. Requiring this information is expected to yield about $220m/year.

- Due to a Supreme Court ruling on the language of the current tax code, there is a six year statute of limitations on being found to have underpayed tax on income, but not if you overstate the base value of property. This rule would bring underpaid tax on income and underpaid tax on capital gains under the same statute of limitations, expecting to yield $130m/yr.

- Currently passports can be denied for failure to pay child support, but not for failure to pay taxes. This rule would require denying passports to tax deadbeats above a certain level. The “no tax deadbeat holidays in Brazil” provision would yield $38.8m/yr.

- Under current IRA and 401(k) rules, holders have to start taking taxable distributions by the time they reach 70 yrs, 6 months of age. But if a young beneficiary inherits an IRA or 401(k), that can mean tax-free interest income for decades. This provision would require distribution to beneficiaries within five years unless they are within 10 years of the age of the original holder, someone with special needs, a minor, or the spouse of the holder. This “no grown-up IRA trust fund baby for life” rule would yield $370m/yr.

Now, some of these things are changes that leave rates completely alone, and just make it harder on deadbeats, others may involve some changes in actual tax obligations … but some of these didn’t make it out of committee.

After all, the currrent “tax deadbeat holiday in Brazil” rule, and the “grown up IRA trust fund baby for life” rule both obviously have to stay, for the Good of the Republic. And the dangerous requirement on the upper middle class and wealthy to say what property they are taking the mortgage interest rates deduction on, when they took out the loan and how much they owe is delayed until the end of 2015, to give our wealthy time to arm themselves to face this dangerous onslaught against their ability to cheat the general public.

Amendments more in line (pdf) with the Republican desire to defend the Republic include putting additional due diligence requirements on getting the childcare tax credits ~ because we damn well know in our bones that people taking care of children are likely tax cheats ~ and … well, let me copy and paste it from Bloomberg, so I don’t have to type the words myself:

Both chambers’ measures would be financed by higher customs fees and by letting companies delay contributions to employee pension plans.

That’s right: fund a crutch for the Federal Highway Trust Fund crisis by making the Employee Pension Fund Underfunding Crisis worse.

A Crutch Isn’t Enough for a Compound Fracture

![]() But as I’ve written before in the Sunday Train (parts 1 and part 2), this is not a short term problem. Therefore, a short term loan of crutches is not going to be enough. Indeed, we have this package of measures with anticipated impacts over ten years … in order to kick the can down the road by less than a year, since, as Bloomberg Business Week described this process on Friday:

But as I’ve written before in the Sunday Train (parts 1 and part 2), this is not a short term problem. Therefore, a short term loan of crutches is not going to be enough. Indeed, we have this package of measures with anticipated impacts over ten years … in order to kick the can down the road by less than a year, since, as Bloomberg Business Week described this process on Friday:

Lawmakers in Congress are uniting behind a plan to replenish the U.S. fund for road and mass-transit projects through May 2015 as they delay a debate over raising taxes for long-term infrastructure financing.

The problem, however, is that our basic system of transportation funding does not fit our economy following the collapse of the Sprawl Suburban Housing bubble and in the midst of the exhaustion of the cheap petroleum upon which we built the Sprawl Suburban Housing system.

Our highway funding system is based on the twin assumptions that Vehicle Miles Traveled will always steadily increase, and that real Gasoline and Diesel Tax Receipts Per Mile will never dramatically decline. Under those two assumptions, we never have to maintain roads on a financially sustainable basis, because by the time the major maintenance work is required, it will be drawn from a larger total Fuel Tax Stream.

But Vehicle Miles Traveled per person are dropping. There is a long debate as to why, whether its because “Millenials” have different attitudes to transport, or because the combined Austerity onslaught on the economy by the Republican House and the Obama Administration is depressing employment and with it commuting transport … but whatever the reason, there is no reason to expect that the the trend will reverse. Even though the population continues to grow, the declining Vehicle Miles Traveled per person means that the century long trend of increased Vehicles Miles Traveled appears to have peaked. The total may stabilize, as population growth offsets the per person decline. It may drop, if the per person decline outpaces population growth. But there’s no particular reason to expect it to start increasing again.

But Vehicle Miles Traveled per person are dropping. There is a long debate as to why, whether its because “Millenials” have different attitudes to transport, or because the combined Austerity onslaught on the economy by the Republican House and the Obama Administration is depressing employment and with it commuting transport … but whatever the reason, there is no reason to expect that the the trend will reverse. Even though the population continues to grow, the declining Vehicle Miles Traveled per person means that the century long trend of increased Vehicles Miles Traveled appears to have peaked. The total may stabilize, as population growth offsets the per person decline. It may drop, if the per person decline outpaces population growth. But there’s no particular reason to expect it to start increasing again.

Which means that unfunded and underfunded maintenance will increase, since we have a system built on a century long expectation that in twenty or thirty year’s time, maintenance can be done funded by fuel tax receipts growing because of more miles driven per person.

Just that alone would put us on the course to crisis. But not only are people driving fewer miles (per person), they are also paying lower fuel taxes per mile to do that driving. Part of that is the fact that the fuel tax is fixed in nominal terms and is not adjusted for inflation … so the purchasing power of the tax on each gallon of gasoline and diesel has been dropping for several decades now.

And part of that is that fuel efficiency is increasing, so people are buying less fuel per mile. And while the tax is collected on the fuel … the damage is done by each mile of driving. With fuel efficiency standards set to double fuel efficiency by 2025, the per-mile-damage fuel tax collected will fall to about half of what it is today.

Indeed, the existence of the diesel and gas taxes leads many motorists to believe that they are “paying their way”, but as I discussed in Sunday Train: Freight Transport and the Highway Funding Crisis, Part1, in terms of the costs being imposed on the system by motor vehicles, only 43% of the need is met with fuel taxes, 45% is met with subsidies from Federal, state and local governments, and the balance is not being met at all, with the lack of funding for work meaning that the roads continue to fall apart.

This is, in other words, is a leading example of the general situation that The Onion satirized in their piece, FBI Uncovers Al-Qaeda Plot To Just Sit Back And Enjoy Collapse Of United States:

This is, in other words, is a leading example of the general situation that The Onion satirized in their piece, FBI Uncovers Al-Qaeda Plot To Just Sit Back And Enjoy Collapse Of United States:

Multiple intelligence agencies confirmed that the militant Islamist organization and its numerous affiliates intend to carry out a massive, coordinated plan to stand aside and watch America’s increasingly rapid decline, with terrorist operatives across the globe reportedly mobilizing to take it easy, relax, and savor the spectacle as it unfolds.

“We have intercepted electronic communication indicating that al-Qaeda members are actively plotting to stay out of the way while America as we know it gradually crumbles under the weight of its own self-inflicted debt and disrepair,” FBI Deputy Director Mark F. Giuliano told the assembled press corps. “If this plan succeeds, it will leave behind a nation with a completely dysfunctional economy, collapsing infrastructure, and a catastrophic health crisis afflicting millions across the nation. We want to emphasize that this danger is very real.”

What Can Be Done, Step One: Fix It First

One of the first responses to drowning in debt is to stop buying new things you cannot afford.

One of the first responses to drowning in debt is to stop buying new things you cannot afford.

Now, Modern Monetary Theorists may be tempted to jump in here and start talking about the ability of a country that issues its own currency to pay its own debts issued in its own currency … but if so, hold your horses. The debt I am referring to here is the obligation to keep the stuff built on the public’s behalf in a state of good repair. This is a physical maintenance debt … its up to us whether we step up to the plate like an honest debtor and pay to meet the obligation, or instead take the deadbeat’s approach and simply refuse to pay, allowing the physical infrastructure of our country to decline into disrepair.

But so long as we do not have a system in place to pay for maintenance of existing roads, we should not be adding to the lane miles of roads requiring additional maintenance.

Sp “Fix It First” says that first Highway Fund transfers to each state should be spent bringing eligible state roads and highways up to a state of good repair in a reasonable period of time, and maintain it in a state of good repair on an ongoing basis, before any money is spent on new construction.

Some states may say that they have rapidly growing populations and so they “need to build new roads” … but the Fix It First rule as described says that if they can maintain the roads they already have, they can go ahead an build those new roads. And if they cannot maintain the roads they already have … then kicking the can down the road just means that a larger share of our nation’s population will be subjected to the collapsing road infrastructure of that state.

If politicians like ribbon cuttings, that’s fine. Fund the Highway Fund on a permanent basis at a level that allows maintenance and new construction both. But spending on new construction so that the Congresscritter can go to a ribbon cutting, while they have no intention of finding a way to maintain the road that they are cutting the ribbon, is just being a physical debt deadbeat, and there is no reason that the citizens of the Republic should stand for it.

What Can Be Done, Step Two: Index Fuel Taxes

The same two decades that we have allowed the Federal Highway Fund to slide toward crisis has also seen a brutal attack on the Great American Middle Class, reaching the point of stagnant real incomes for the majority of Americans over the past decade. At the same time, the incomes of the top 10% have been growing, the incomes of the top 1% have been growing rapidly, and the incomes of the top 0.1% have been sky-rocketing.

The same two decades that we have allowed the Federal Highway Fund to slide toward crisis has also seen a brutal attack on the Great American Middle Class, reaching the point of stagnant real incomes for the majority of Americans over the past decade. At the same time, the incomes of the top 10% have been growing, the incomes of the top 1% have been growing rapidly, and the incomes of the top 0.1% have been sky-rocketing.

So catching up on the twenty year long decline in the purchasing power of the Federal Fuel Tax may not be politically feasible, since the steadily declining share of the cost of roads that motorists have been paying has been more than matched by massive increases in costs of the fuel itself, of health care, of higher education, and of a wide range of other things.

But even accepting the long term cut in the Federal Fuel Taxes and the resulting increase in the subsidy being paid by all Americans to those who drive, the increase in that subsidy to driving has got to stop. So the Federal Gas and Diesel Taxes should be indexed to the nominal growth in median incomes or the nominal growth in the cost of construction … whichever is lower.

This will, of course, not “fix” the current shortfall … but it will slow down the rate at which the shortfall gets worse. And with increasing fuel standard, the size of the free ride being given to Motorists is going to continue even if we index the Gas and Diesel taxes. But that only makes it more critical to take whatever steps we can take to slow the growth in the size of motorist’s free ride on everyone else.

What Can Be Done, Step Three: The Steel Interstate

Neither “Fix It First” nor “Slow the Growth of the Motorists Free Ride” actually fix the problem … they both simply down how rapidly the problem gets worse.

Neither “Fix It First” nor “Slow the Growth of the Motorists Free Ride” actually fix the problem … they both simply down how rapidly the problem gets worse.

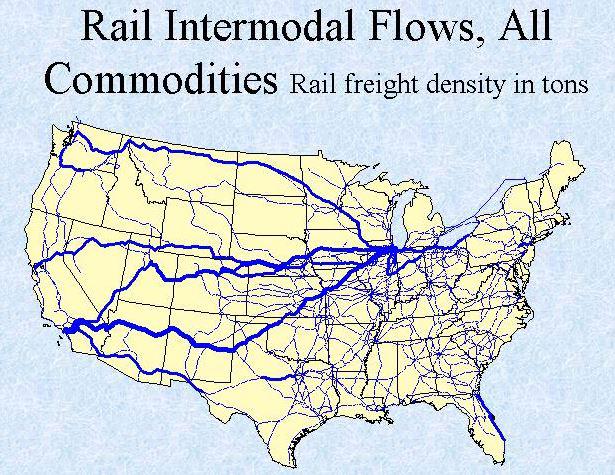

However, building a Steel Interstate system, a system covered in the Sunday Train multiple times, has the ability to contribute to fixing the problem.

The idea of a Steel Interstate is that we provide some form of public financing that focuses on the main long haul freight rail corridors and:

- (1) Electrifies the corridors;

- (2) Improves them to allow 90mph Rapid Freight Rail (which as a side-effect implies 110mph Rapid Passenger Rail); and

- (3) Pays for the Construction and Maintenance Cost with User and Access Fees.

I stress public financing and user funding because it addresses on of the key “Frequently Asked Questions” about Steel Interstate proposals, which is: if electric freight rail is so great, why don’t the railroad do it themselves?

The first part of that is that many of the benefits are not actually received by the railway. When a freight railroad attracts freight that would have gone on a truck, they get the business. They also get the full cost of maintaining the track and right of way. By contrast, on the truck freight side of the equation, the public roads have just received a break on the cost of the heavy truck traffic that is responsible for about half of the ongoing damage to pavements through use. Also, even for a diesel railroad, the greater energy efficiency means fewer CO2 emissions, which would be even lower for an electrified railroad powered by renewable, US generated electricity.

When part of the benefit goes to the reduced public subsidies and reduced distributed costs of pollution, now and in the future, that part of the benefit cannot be recovered from the freight shipper, since its not a benefit that the shipper directly receives.

The second part is that private freight railways are very capital intensive firms, which typically already have fairly high debt burdens, and so their cost of funds is higher than the cost of funds to the public. When Federal bonds require interest rates of from fractions of a percent to 3% to sell, and state and municipal bonds requires interest rates of 3% to 6% to sell, the cost of private finance to a private railway is more like 11%-12%.

The third part is scale. The part of the freight market that higher speed freight rail can capture, particularly with the lower operating costs of electric freight rail, is concentrated in the long haul freight market, for shipments of 500 miles and more. But if you want to capture a 500 mile shipment with a Steel Interstate, you need a Steel Interstate that is 500 miles long. If you want to capture a 1,500 mile shipment with a Steel Interstate, you need a Steel Interstate that is at least a large fraction of 1,500 miles long (a large fraction because the time saved by 1,000 mile Steel Interstate shipment can cover for a certain part of the trip operating on slower speed conventional freight rail corridors).

That scale means that credit markets will demand a steep additional risk premium if the project is being undertaken strictly by a private firm, since a private firm looking to establish a 2,000 mile long Steel Interstate corridor that is not in response to a public policy are subject to being “held up” by state and local governments looking to get a piece of the action.

However, assuming there is not an excessive degree of government (and normally slightly veiled) extortion, there is still a positive return on investment available for investing in a Steel Interstate, likely in the range of a 10% return on investment. And that means that if the public finances the work, user fees and access fees will be able to fund the cost of the work.

And that is vital: shifting truck freight to rail freight is only part of the solution to our Highway Funding Crisis if we are moving that freight from a road transport system that cannot cover its maintenance costs, to a rail transport system that can cover its maintenance costs.

The Steel Interstate will be able to cover its maintenance costs from Access Fees (per mile of upgraded track used) and User Fees (per kWh of electricity consumed). So shifting road freight to rail freight powered by sustainable, renewable electricity will not just reduce transport’s contribution to catastrophic runaway climate change, but it will also ease the burden on our underfunded road transport system.

What Can Be Done, Step Four: Local Electric Transport

We have built our economy on engaging in quite a bit of long haul freight transport, and so we can take a substantial slice out of the unfunded costs of road freight by shifting long haul road freight to rail. But for the unfunded part of road passenger transport, we have to focus on local transport, because the majority of passenger road miles involve local trips. Further, it is local trips where the greatest free ride is being taken by motorists, since, as mentioned in Sunday Train: Freight Transport and the Highway Funding Crisis, Part1, the subsidies of local and intercity road funding from sources other than user paid fuel taxes rise the further down the system you go:

- In 2008, less than three tenths of Federal government funding were subsidies funded from other tax revenues, or else through money creation;

- about four tenths of state government funding were subsidies funded from other tax revenues (and state governments cannot fund with money creation); and

- a dominant nine tenths of local government funding were subsidies funded from other tax revenues.

So we require largest share of government subsidy and the smallest share of user pays from the level of government that tends to rely the most heavily on regressive sales and property taxes, and is most subject to lose-lose “beggar thy neighbor” policies of offering relocation tax breaks to chase the tax base of other local governments.

Our current system of massive operating subsidies to motorists discourages people from adopting alternatives to driving which do not receive the same subsidy. If people get subsidized “free” parking while driving, and pay user fees that cover less than one half of the road damage cost of their road damage costs, while on the other hand receive a smaller level of personal subsidy while taking some other form a transport, that encourages people to drive on the same roads we cannot afford to maintain.

So if it is politically impossible to substantially reduce the massive subsidy to motorists, that means that taking the burden off of our fuel-funded road system requires giving a subsidy to alternatives to local driving.

I understand that some may object that it is equally politically impossible to do that on the scale required. However I argue that it is not equally politically impossible:

- The political impossibility of raising gas taxes to a high enough level to eliminate the subsidy to driving is not just that it is impossible to do it under the current political balance of power, but that if we were to somehow succeed in doing it, the political backlash would overturn the policy in two to four years time at most.

- However, while a subsidy to alternatives to driving of sufficient scale is impossible under the current political balance of power, there is every reason to believe that if achieved, it would grow in popularity, since it would drive increasing employment, offer growing transport choices to people, and result in better roads for those who continue to drive.

So this part is something that, as of today, we couldn’t start doing, but if we could ever find a way to start doing it, we could keep on doing.

And I am going to tilt the field in its favor, because the way I am going to specify it will offer immediate and growing financial relief to overstretched local and state departments of transportation.

Part 1: An Electric Transport Investment Credit (ETIC). This is a $50 annual credit to each adult US citizen (roughly 220m total) to be directed to the interest cost of Federal Energy Independence Bonds to fund investment in Electric Transport. This is used as desired by individual taxpayers to:

Part 1: An Electric Transport Investment Credit (ETIC). This is a $50 annual credit to each adult US citizen (roughly 220m total) to be directed to the interest cost of Federal Energy Independence Bonds to fund investment in Electric Transport. This is used as desired by individual taxpayers to:

- Finance or help finance the purchase of an electric vehicle; or

- Direct to a Regional Transit Authority that is investing in the construction of a qualifying electric common carrier transport system, in return for credit on trips taken on the services of that RTA.

This is fully funded for all eligible recipients. All funds that are not directed by their eligible recipients in each state go into a competitive grant fund for capital grants for the construction of additional electric transport projects in that state, under the direction of a state grant panel, just as in the “Super-TIGER” proposal I covered on 1 June, 2014.

Part 2: An Electric Transport Maintenance Credit. This is a $50 annual credit to each taxpayer to be directed to the maintenance cost of their primary form of electric transport. For owners of personal electric vehicles, this would go to their local transport authority for the roads that are open to that form of transport (that is, incorporated city, town or village, or unincorporated county or reservation). For those that do not own personal electric vehicles, this would go to the organization maintaining the right of way of the qualifying common carrier electric transport in their community.

Note that funds from a neighborhood electric vehicle that is not allowed on streets with speed limits higher than 35mph could not be spent on roads and streets with those higher speed limits. Also, towns and cities that deny cyclists the right to use the public right of way when a “separate but equal” segregated cycle path is provided could not use the funds from electric bikes on those segregated roadways.

In this case, the only way for funds to fail to be directed to maintenance of the right of way for some electric transport is if there is no common carrier electric transport available, whether trolleybus, streetcar, light rail, or electric heavy rail in the local area. So these funds are directed into a capital fund for the local community to either fund investment in a qualifying electric transport system, and/or to further help finance local resident acquisition of personal electric vehicles, at the local community’s discretion.

If a local community should elect not to participate at all, their share would be added to the pool of state competitive grants which is based on unallocated ETICs.

With roughly 220m adult US citizens, $100 annual credits are a cost of $22b annually. This is, of course, only a fraction of the annual subsidy given to and tolerance for external costs allowed to motorists, but it is a sufficient amount to get started. And the economic boost from the program would be substantially greater than $22b per year, since up to half of the credits go to interest subsidy, which at public bond rates of 3% to 5% could finance a capital fund of from $220b to $360b.

With roughly 220m adult US citizens, $100 annual credits are a cost of $22b annually. This is, of course, only a fraction of the annual subsidy given to and tolerance for external costs allowed to motorists, but it is a sufficient amount to get started. And the economic boost from the program would be substantially greater than $22b per year, since up to half of the credits go to interest subsidy, which at public bond rates of 3% to 5% could finance a capital fund of from $220b to $360b.

Now, of course, we “can’t do it”. But if we could, the benefits would be both strong and immediate enough to allow us to keep doing it.

Indeed, if, over time, we release enough of our citizens from dependence on automotive transport, we might one day create a political terrain in which it is no longer political necessary to give a free ride to a mode of transport that kills and injures so many Americans, damages the health of so many, and causes to massive environmental destruction as the automobile.

Conclusions & Conversations

The Sunday Train only really begins when you hop and board and join the conversation, and so that is where I want to turn it over to you.

What kinds of alternatives would you like to see to the road-bound transport which we continue to build roads for, even as we have no arrangements in sight to maintain the roads that we already have?

1 comments

Author

h/t Breakfast Club.