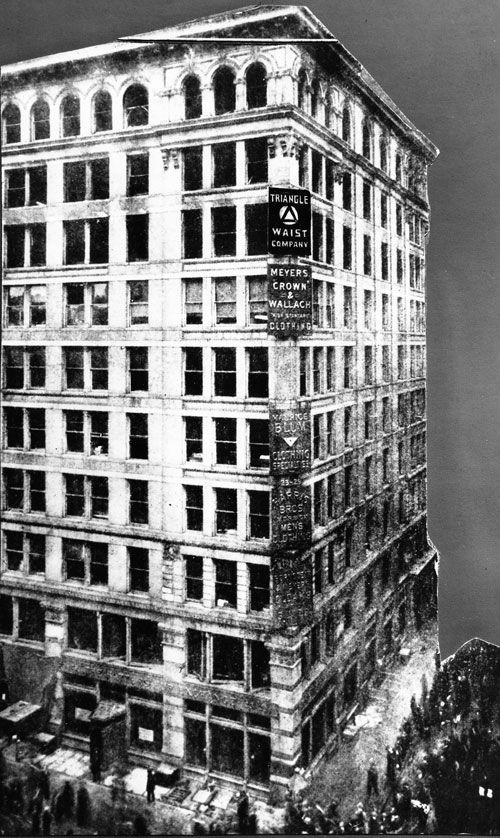

Today we mark the anniversary of two tragic fires that occurred in New York City. In 1911, the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire claimed 146 lives. On the same date 79 years later in the Bronx borough of New York City, the Happy Land fire killed 87 people, the most deadly fire in the city since 1911.

The Triangle Factory fire lead to major changes in fire safety and building codes. In New York State alone there were sixty laws passed. Those laws mandated better building access and egress, fireproofing requirements, the availability of fire extinguishers, the installation of alarm systems and automatic sprinklers, better eating and toilet facilities for workers, and limited the number of hours that women and children could work. The fire also gave rise to two important organizations the American Society of Safety Engineers and the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU).

Some of the most important changes that resulted from the tragic deaths at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire were the reforms to work place health and safety conditions. Modern buildings now must conform to fire safety and occupancy standards. The Asch building loft were 500 women labored at overcrowded worktables did not have a sprinkler system, the exits were inadequate and locked, the passages were narrow and blocked and the fire escapes were unsafe. The fire compelled New York City to create the Bureau of Fire Prevention, which required stairwells, fire alarms, extinguishers and hoses be installed in all buildings and regularly conducts building inspection to insure compliance. The Bureau also determines maximum occupancy. The year after the fire the NY the legislature passed eight bills addressing workplace sanitation, injury on the job, rest periods and child labor. In 1913, the Factory Investigating Commission recommended that 25 new bills be passed mandating fireproof stairways and the safe construction of fire escapes, that doorways be a certain number of feet wide, and that older multi-storied buildings be inspected. In 1916, smoking was also outlawed in factories.

Some of the most important changes that resulted from the tragic deaths at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire were the reforms to work place health and safety conditions. Modern buildings now must conform to fire safety and occupancy standards. The Asch building loft were 500 women labored at overcrowded worktables did not have a sprinkler system, the exits were inadequate and locked, the passages were narrow and blocked and the fire escapes were unsafe. The fire compelled New York City to create the Bureau of Fire Prevention, which required stairwells, fire alarms, extinguishers and hoses be installed in all buildings and regularly conducts building inspection to insure compliance. The Bureau also determines maximum occupancy. The year after the fire the NY the legislature passed eight bills addressing workplace sanitation, injury on the job, rest periods and child labor. In 1913, the Factory Investigating Commission recommended that 25 new bills be passed mandating fireproof stairways and the safe construction of fire escapes, that doorways be a certain number of feet wide, and that older multi-storied buildings be inspected. In 1916, smoking was also outlawed in factories.

Frances Perkins, who would later become Franklin D. Roosevelt‘s Secretary of Labor, witnessed the women jumping from the windows that day. She would later comment that it was “the day the New Deal began.” In the ’30s, the New Deal included many of these provisions on the federal level. In 1933, Congress passed the National Industrial Recovery Act which also protected collective bargaining rights for unions.

These are just a few of the safety rules that resulted from that terrible day:

- The law was instituted requiring employers to provide sprinklers for workplaces with more than 50 people.

- Regulations require that enough exit stairways to accommodate all building occupants and direct passageways to those exits that are of minimum width. Additionally, all exit doors shall remain unlocked, requiring no special knowledge or tools to open.

- Maximum occupancy regulations established occupant loads for building rooms under all probable conditions to prevent dangerous overcrowding.

- Regulations for exits and openings created minimum 32in pathways and doors that open in the direction of travel, reducing the bottle neck effect that wasted precious minutes.

- Fire drills for offices, apartment buildings, schools and health facilities train workers and occupants regularly for exit procedures, using audible alarms, visible exit signs, and off site gathering spots.

- Organizers pushed for, and won, egress regulations for the workplace, creating continuous passageways, aisles and corridors for direct access to every available exit.

Because of these reforms deaths from fires in the work place were drastically reduced. Unions now are focusing on other factors that affect work place safety. Now in states like Wisconsin, Michigan and Ohio, Republican dominated state legislatures are trying to end workers right to collective bargaining as an excuse to reduce state budgets while giving tax breaks to their corporate masters who financed their elections. Citizens are fighting back in court and at the ballot box with recalls and referendums.

The Happy Land fire was an act of arson that killed 87 people trapped in the unlicensed Happy Land social club at 1959 Southern Boulevard in the West Farms section of the Bronx in New York City on March 25, 1990. Most of the victims were young Hondurans celebrating Carnival, many of them part of the Garifuna American community. Unemployed Cuban refugee Julio González, whose former girlfriend was employed at the club, was arrested soon afterward and ultimately convicted of arson and murder.

Before the blaze, Happy Land was ordered closed for building code violations during November 1988. Violations included lack of fire exits, alarms or sprinkler system. No follow-up by the fire department was documented. [..]

Before the blaze, Happy Land was ordered closed for building code violations in November 1988. Violations included no fire exits, alarms or sprinkler system. No follow-up by the fire department was documented.

The evening of the fire, Gonzalez had argued with his former girlfriend, Lydia Feliciano, a coat check girl at the club, urging her to quit. She claimed that she had had enough of him and wanted nothing to do with him anymore. Gonzalez tried to fight back into the club but was ejected by the bouncer. He was heard to scream drunken threats in the process. Gonzalez was enraged, not just because of losing Lydia, but also because he had recently lost his job at a lamp factory, was impoverished, and had virtually no companions. Gonzalez returned to the establishment with a plastic container of gasoline which he found on the ground and had filled at a gas station. He spread the fuel on the only staircase into the club. Two matches were then used to ignite the gasoline.

The fire exits had been blocked to prevent people from entering without paying the cover charge. In the panic that ensued, a few people escaped by breaking a metal gate over one door.

Gonzalez then returned home, took off his gasoline-soaked clothes and fell asleep. He was arrested the following afternoon after authorities interviewed Lydia Feliciano and learned of the previous night’s argument. Once advised of his rights, he admitted to starting the blaze. A psychological examination found him to be not responsible due to mental illness or defect; but the jury, after deliberation, found him to be criminally responsible.

Found guilty on August 19, 1991, of 87 counts of arson and 87 counts of murder, Gonzalez was charged with 174 counts of murder- two for each victim he was sentence maximum of 25 years. It was the most substantial prison term ever imposed in the state of New York. He will be eligible for parole in March 2015.

The building that housed Happy Land club was managed in part by Jay Weiss, at the time the husband of actress Kathleen Turner. The New Yorker quoted Turner saying that “the fire was unfortunate but could have happened at a McDonald’s.” The building’s owner, Alex DiLorenzo, and leaseholders Weiss and Morris Jaffe, were found not criminally responsible, since they had tried to close the club and evict the tenant. [..]

Although the Bronx District Attorney said they were not responsible criminally, the New York City Corporation Counsel filed misdemeanor charges during February 1991 against DiLorenzo, the building owner, and Weiss, the landlord. These charges claimed that the owner and landlord were responsible for the building code violations caused by their tenant. They both pleaded guilty during May 1992, agreeing to perform community service and paying $150,000 towards a community center for Hondurans in the Bronx.

There was also a $5 billion lawsuit filed by the victims and their families against the owner, landlord, city, and some building material manufacturers. That suit was settled during July 1995 for $15.8 million or $163,000 per victim. The lesser amount was due mostly to unrelated financial difficulties of the landlord. [..]

The street outside the former Happy Land social club has been renamed “The Plaza of the Eighty-Seven” in memory of the victims. Five of the victims were students at nearby Theodore Roosevelt High School, which had a memorial service for the victims in April 1990. A memorial was erected directly across the street from the former establishment with the names of all 87 victims inscribed on it.

Only six people escaped from that fire. The building was condemned 24 hours later and eventually torn down.

Gonzalez died in 2016 of a heart attack while still in prison.

Like the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, the Happy Land fire provoked a similar response awakening New Yorkers to oppressive and dangerous work conditions and fire hazards in many parts of the city. City officials belatedly formed a task force to toughen and enforce the regulations governing social clubs. About a third of the 1,500 places that were inspected were closed, and a year later, about 320 were still shut down. That climate of widespread violations and lax enforcement was noted by the sentencing judge, Justice Burton B. Roberts of State Supreme Court in the Bronx. “There are many to be blamed” for the fire, he said, “not just Julio Gonzalez.”

We must never forget what the 146 victims of Triangle and the 87 victims of Happy Land represent. Ever.

Recent Comments