(4 pm. – promoted by ek hornbeck)

The Occupy movement has sent out a Call to Action for a June 20th “Global Festival” to celebrate their global demand for a Universal Living Wage:

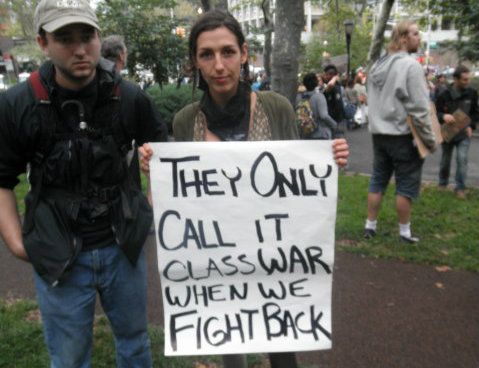

The regime of wholesale robbery – what the 1% call “austerity” – is already falling across Europe, and soon will fall across the world. But the inevitable collapse of austerity is not enough. We, the 99%, demand a world beyond Wall Street. We demand a system where everyone can not only survive, but flourish. To reach this world, we are raising our voices to demand a universal living wage.

We call on all occupies, unions, community organizations, immigrants rights groups, bodies, religious organizations, environmental groups, anti-poverty activists, and everyone to join us June 20th, 2012 for a new holiday for the 99%: A Global Festival for the Universal Living Wage.

No, Karl Marx, dead since 1883, is not now able to report on the events of the Occupy Movement, as he did on events of the U.S.’s Civil War for the NY Herald Tribune in the 1860’s and the Paris Commune in the 1870’s, but strangely, to this day, the mere mention of his name still strikes terror into the hearts of global capitalists and their media puppets, such as Sean Hannity. Link to…

There must be a reason that the capitalist powers of the 21st century tremble at his name 129 years after his death, his writing must have been very dangerous indeed. How much they must be fear of Tim Poole’s live-streaming. No wonder they arrested him this month in Chicago!. Read below to understand why Karl Marx, and especially his writing on the Paris Commune, was such a danger to capitalism.

One of the reasons is, no doubt, that there is still so much trembling at the name of Karl Marx is that he analyzed so accurately and thoroughly in his economic work, Capital, the very basic elements of the operation of the capitalist economic system, starting from the profits gained from the simplest commodity, the same profits which have accumulated to the phenomenal wealth now controlled by our elites. He showed that their wealth flowed from stealing the labor power of their workers: pay a worker for 6 hours work, but work him for 10, 12, or 14 or more. Steal enough hours and you become rich.

Accumulate enough of those stolen hours and you end up with the wealth of Bank of America and J.P. Morgan and similar cronies. And, not satisfied by stealing from workers and pensioners, they voted themselves more from the public treasury via Congress and the Federal Reserve. Thus we now have all profits and bailouts to the banksters, while the workers, the taxpayers and poor pay the banksters gambling losses, lose their homes and their jobs, and are left to stand on lines at the Unemployment Office and the Food Bank.

Karl Marx was not only an economist and a historian, but a revolutionary journalist who reported on the Occupy events of his day, including The Paris Commune (Introduction by Frederick Engels) of March 29, 1871 to May 28, 1971.

Marx, (5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a consummate internationalist who would have roundly applauded Occupy Wall Street’s call for a global living wage and their focused attacks upon Finance Capitalism’s big banksters. One can can imagine him on the ground with a live-stream microphone in his hand, reporting from Tunisa, Spain, Greece and New York.

Originally trained in law, history and philosophy, Marx’s revolutionary writings precluded an academic post and then brought threats of arrest in his native Prussia (Germany), forcing Marx to move to France, where, as a socialist journalist, he was thereafter expelled, moving then to Belgium, which stay ended shortly after Marx and his long-time collaborator, Frederich Engels, published The Communist Manifesto at the behest of Belgium’s Communist league. When Belgium workers began to put The Communist Manifesto into practice, Belgium likewise expelled Marx.

After returning briefly to Germany before yet another forced exile, he moved to England in 1849, where he remained and published most of his major works, maintaining active contacts by letter with his socialist friends and associates throughout Europe. (Oh, how he would have loved the internet, Skype and, especially, live-streaming! )

Many of Marx’s European contacts were to become active members of the International Working Men’s Association Link to, later known as the First international, of which Marx was a founder and general secretary. French members of the First International were to play an important role in the formation and actions of the Paris Commune of 1871.

Karl Marx, reported on the Paris Commune of 1871 from England, later published as a part of “The Civil War In France” [link

http://www.marxists.org/… ], from which the following quotes are taken, unless otherwise indicated.

In Paris, in March of 1871, the workers, artisans and general population , the 99 Percenters of those days, had taken control of its government by forming self-organized communes (councils) in each of 20 “Arrondisments” (administrative districts) of Paris and held off the French Provisional government and independently ran and defended Paris for two months, ending in a bloodbath by provisional forces when they re-took the city.

Karl Marx, writing in his Third Address to the International Workingmen’s Association, only two days after the fall of the Commune wrote:

The great social measure of the Commune was its own working existence. Its special measures could but betoken the tendency of a government of the people by the people. Such were the abolition of the nightwork of journeymen bakers; the prohibition, under penalty, of the employers’ practice to reduce wages by levying upon their workpeople fines under manifold pretexts – a process in which the employer combines in his own person the parts of legislator, judge, and executor, and filches the money to boot. Another measure of this class was the surrender to associations of workmen, under reserve of compensation, of all closed workshops and factories, no matter whether the respective capitalists had absconded or preferred to strike work.

Interestingly and perhaps relevant for today when Occupy Wall Street has focused on the big banks and financial institutions as the cause of the globe’s massive economic inequality, was the fact that Marx criticized the Communards (in a private letter to Kugelman in 1871) only for being too cautious in running their city, and not making use of the money that was sitting in the national bank in Paris, although they did issue a decree nationalizing all church property. They likely could have fed all of then starving Paris with the proceeds of the money that had previously been stolen from the people and was sitting in the bank and the coffers of the church. In his public writing, he was more circumspect:

The financial measures of the Commune, remarkable for their sagacity and moderation, could only be such as were compatible with the state of a besieged town. Considering the colossal robberies committed upon the city of Paris by the great financial companies and contractors, under the protection of Haussman,[J] the Commune would have had an incomparably better title to confiscate their property than Louis Napoleon had against the Orleans family. The Hohenzollern and the English oligarchs, who both have derived a good deal of their estates from church plunders, were, of course, greatly shocked at the Commune clearing but 8,000F out of secularization.

The Paris Commune was ultimately unable to sustain itself against the attacks of the counter-revolutionary Thiers government, a provisional government which had taken over after Louis Bonaparte, then the French President, had lost his capricious war against Prussia. Bonaparte’s was had been initiated “for the greater glory of France” to re-take a few hundred kilometers of land lost to Prussia in a previous war. The unpopular Thiers, although forced by the Parisians to retreat in tatters from the Paris capital to Versailles, had signed a peace treaty with Prussia and was in the process of paying Prussia’s Bismarck huge war reparations, to be paid, of course by the 99%, not those who had supported and lost the disastrous war.

As part of the reparations, Prussia had agreed to aid Thiers in taking back Paris by releasing thousands of French soldiers held hostage since the French debacle at the battle of Sedan. The Paris Commune, despite courageous street-fighting had thus been vanquished by the resulting over-whelming numbers of French provisional troops. Thus did the Prussian and French oligarchs unite to fight the common enemy: the working class uprising.

Indeed, the Paris Commune was itself a product of the devastating war which had resulted in a four month Prussian siege of Paris. Ordinary French citizens had banded together into militias to defend Paris, even raising their own money to buy canons and small arms, which they controlled. The siege had officially ended when Thiers signed a peace treaty which was hugely unpopular in Paris. Thiers immediately tried to take back the canons and arms from the militias, going as far as ordering his putatively “loyal” troops to fire on the population which had taken to the streets to defend their arms. The troops, however, began to mingle with the people and refused to fire on them.

Thiers then took his provisional government and fled Paris in disgrace to Versailles.

After the Thiers capitulation to the Prussians, the organization which had run the militias defense of Paris, composed of many socialists and militants, subsequently called for the election of new communes in Paris.

A majority of those elected to the Communes had been active in the militias and continued their efforts to supply and run Paris, this time as ordinary citizens under the flag of the Paris Commune, declared on March 29, 1871. The councils were established in each of the 20 Arrondissments, meeting daily to debate, decree and take actions, issuing their directives by pamphlets and “word of mouth” communications. (There were no microphones in existence then, so no “Mic Check” then, “word of mouth” was standard procedure.)

Marx hailed the fact that this was the first French government to not only legislate but act themselves to carry out the new laws, and their actions were carried out by ordinary French citizens who were democratically elected and subject to immediate recall if they did not carry out the directives of their councils.

In a rough sketch of national organization, which the Commune had no time to develop, it states clearly that the Commune was to be the political form of even the smallest country hamlet, and that in the rural districts the standing army was to be replaced by a national militia, with an extremely short term of service. The rural communities of every district were to administer their common affairs by an assembly of delegates in the central town, and these district assemblies were again to send deputies to the National Delegation in Paris, each delegate to be at any time revocable and bound by the mandat imperatif (formal instructions) of his constituents. The few but important functions which would still remain for a central government were not to be suppressed, as has been intentionally misstated, but were to be discharged by Communal and thereafter responsible agents.

The Paris Commune’s very first decree had been to separation of the church from the state and the nationalization of all church property. At that period in France, the church was enormously wealthy and officially controlled many facets of French life, even generating an official “Morality police” to enforce its edicts. The Commune disbanded the “morality police”, and removed the church from its control over French education. As to the regular police, the Commune re-organized the force and put them under the direct supervision of the Communes. The Commune declared education free and open to all, without religious instruction.

Other decrees removed all special benefits previously accorded to their elected officials that all those working for the Communes would be paid equal wages, equivalent to that a ordinary working person. The factories that had been closed or abandoned by their owners during the previous Prussian siege were declared to be turned over to their workers to run and manage (subject to later compensation to owners). Thus creating the potential for worker-owned cooperatives on a city-wide scale.

The communards hoped, of course, that their model of self-government would be taken up throughout France, if not all of Europe. This was effectively undermined by seizure and burning of all information from Paris to the outlying districts and towns by the Thiers government. Isolated from support from Paris, communes started in other cities were easily suppressed.

The Paris Commune deliberately and consciously eschewed the national chauvinism of the day, especially attacks on individual Prussians, by electing those of non-French ethnicity to positions in the commune, including electing a Prussian worker to head its Labor Committee, many other Europeans participated as well. In so doing, they put their internationalism into practice.

Marx stressed the historic significance of working class self-rule:

<

Just as Arabs, Spanish, Greeks, Canadians,and British citizens contributed to the early developments of Occupy Wall Street on the spot in New York, (and Americans participated in Britain’s occupy movement and elsewhere), so the Occupy Movement today is demonstrating its internationalism by maintaining close contacts with hundreds of groups throughout the world who are in the streets protesting the gross economic and social inequality created by a relatively small group of global capitalists. Thus, New York Occupy requests a living wage for all – world wide.

Marx stressed the historic significance of the Commune’s principles of political and economic self-rule:

The multiplicity of interpretations to which the Commune has been subjected, and the multiplicity of interests which construed it in their favor, show that it was a thoroughly expansive political form, while all the previous forms of government had been emphatically repressive. Its true secret was this:

It was essentially a working class government, the product of the struggle of the producing against the appropriating class, the political form at last discovered under which to work out the economical emancipation of labor.

Except on this last condition, the Communal Constitution would have been an impossibility and a delusion. The political rule of the producer cannot co-exist with the perpetuation of his social slavery. The Commune was therefore to serve as a lever for uprooting the economical foundation upon which rests the existence of classes, and therefore of class rule. With labor emancipated, every man becomes a working man, and productive labor ceases to be a class attribute.

Marx likewise points out a problem faced by the Paris Commune that is likely common to all the current world movements:

In every revolution there intrude, at the side of its true agents, men of different stamp; some of them survivors of and devotees to past revolutions, without insight into the present movement, but preserving popular influence by their known honesty and courage, or by the sheer force of tradition; others mere brawlers who, by dint of repeating year after year the same set of stereotyped declarations against the government of the day, have sneaked into the reputation of revolutionists of the first water. After March 18, some such men did also turn up, and in some cases contrived to play pre-eminent parts. As far as their power went, they hampered the real action of the working class, exactly as men of that sort have hampered the full development of every previous revolution. They are an unavoidable evil: with time they are shaken off; but time was not allowed to the Commune.

Apparently, the Communards faced their own “Black Bloc” problems, and likely had to deal with the egoists and those who otherwise obstructed or held the movement back.

Some in the Paris Commune feared taking the offensive against the bourgeoisie and its Provisional Government supporters. Thus Marx noted that the failure of the communards to follow Thiers and his Provisional government when it retreated in tatters to Versailles and continue the attack on them gave Thiers the time he needed to rebuild his army and generate massive propaganda against the Paris Commune from Versailles.

Eventually, Thiers became strong enough to completely suppress news from the Paris Commune from reaching the rest of the country. Commune movements in several cities were individually picked off and suppressed. Thiers put an effective “information cordon” around Paris, seizing and burning any pamphlets or letters originating in Paris which carried news from the Commune.

Our modern gang of capitalists can “cordon off ” news of Occupy Wall Street and other movements in the world simply by ordering their corporate media to give it no coverage, but they haven’t been totally successful. Thanks to the internet our independent journalists have been able to live-stream events and independent blogs reporting Occupy News have been able to embarrass the national media to giving some paltry coverage. Unfortunately, only a minority of our citizens have access to the efforts of independent our independent media.. If it had not been for the wide-spread police violence, the national media may have ignored Occupy completely.

In the U.S., as in Paris of 1871, the violence came from the counter-revolutionary forces, not the rebels. Indeed, Marx noted that the streets of Paris were completely crime and violence free while the Communards were in charge. All the violence was initiated by Thiers and his provisional government.

The actions and ideas of the Communards have been passed on to the world by the independent revolutionary journalists of their day, by letters smuggled to the outside world, by articles written after the events, such as those by Karl Marx and Frederick Engels and many other revolutionary journalists of the time. And all this despite the Provisional Government’s efforts to “cordon off” their ideas and actions from the world.

So, without, e-mail, text-messages, YouTube or live-stream, without microphones or Skype, without even telephones, the communards not only managed to communicate with each other, debate their ideas and programs and organize themselves into their work committees.

Despite the limitations under which the Communards lived and fought, their historic actions in the Paris Commune have reverberated throughout subsequent history: The workers took over and ran the city of Paris in 1871, they called for direct management of communal government by the people “to the smallest hamlet”, economic equality among workers and worker control and management of the factories.

Let us hope the ordinary people across the world, those of the 99%, of today, can do likewise and can take over and create their own Paris Communes throughout the world in the near future. Surely Occupy’s demand for a “Global Living Wage” is a first step in stopping the theft of human labor and the degradation of human dignity we have all suffered under global capitalism for far too long.

An excellent compilations of manifestos, declarations, minutes of Commune meetings and reports by actual participants can be found in Communards: The Story of the Paris Commune of 1871 As Told By Those Who Fought for it, by Mitchell Abidor (Marxist International Archive, 2010), available from Amazon for download. A French Commission interviewed participants in the Commune in 1898, asking them why they had been there and what they done. Their interviews, reproduced in Communardsmakes for fascinating reading.

1 comments

Author

We are a collective of anticapitalist authors. Some of us are better than others at answering comments here, but you can always catch us on Facebook or in join our Facebook Group.

You can also follow us on Twitter.