(2 pm. – promoted by ek hornbeck)

Burning the Midnight Oil for Living Energy Independence

Crossposted from its home station at Voices on the Square

Firedog Lake: California Legislature Passes High Speed Rail Bond Issue, Moving Project Forward ~ David Dayen

…

In a closely watched vote of the California state Senate, a bill to issue the first $5.8 billion in bonds for the construction of high speed rail lines passed 21-16. It needed all 21 votes to pass. Four Democrats voted no – including Allen Lowenthal, the Democratic candidate for Congress in CA-47, and Fran Pavley, the author of the state’s historic global warming law – but ultimately, just enough Democrats voted in favor of the bonds for them to pass. Joe Simitian and Mark DeSaulnier were the other Democrats who opposed the bill.

…

This does not end the battle for high speed rail. Between the bond issue and the federal money, that covers only about 1/5 of the total funding needed for the full project, which would connect Sacramento and San Diego and all points in between by high speed rail. But if this died today, you can be certain that nothing would ever get built. The federal government was prepared to take away the $3.2 billion in stimulus dollars earmarked for this stage of the project. And faith in the future of high speed rail in California – and indeed the nation – would have been sapped.

So … what now?

The Elephant in the Room for Intercity Transport

When looking at infrastructure construction for intercity transportation, one has to look ahead. And looking ahead to the 2030’s, intercity transportation in much of the United States faces a massive challenge, because it relies almost exclusively on driving and flying, both dependent on imported petroleum in order to move people long distances.

And we know that the price of imported petroleum is going to be going up over the current decade and also in the decade ahead. The big debate is whether it will go up substantially in that time period, or whether it will soar to levels most people cannot currently imagine.

After all, while petroleum prices of $5 a gallon, giving gasoline prices somewhere around $7 a gallon will have substantial impacts at the margin, they are also prices that countries who tax gasoline at sensible levels for oil importers has been experiencing over the past decade, and many of them have transport dominated by the automobile … just not as heavily as in the US.

But petroleum is tremendously useful stuff, and it is quite possible for the price of petroleum over the next two decades to really soar. How high it can go is difficult to predict, but we do know that many of the big oil fields discovered post WWII will be dropping out of production over the next twenty years, and discovery of new oil worldwide has been declining since the 1990’s. Sooner or later, production is going to track the decline in earlier production, and the high value uses of petroleum will start to outbid the combustion of petroleum to move a ton of steel around to move 1.56 passengers around the countryside.

And those industrial interests on the side of not burning up such a valuable chemical feedstock will be able to join the “side of the angels” because they will be on the side of opposing Greenhouse Gas emissions and mitigating the Climate Change crisis that is already starting to show us its first warning tremors. But we are already on track for much bigger climate shocks ahead. By the 2030’s, the Northwest Passage will be open and the shorelines of a Seventh Sea will be opening up a new frontier as the economies of the Arctic Tigers of Canada, Russia, Alaska in the US, Greenland, Sweden and Norway will be roaring. For a fictional treatment that brings this vividly to life, see Tobias Buckell’s Arctic Rising.

Gambling our intercity transport future on petroleum is an unacceptable risk.

And while work progresses on electric cars and sustainably fueled planes, there is one mature, proven, technology for intercity transport for trips of 100miles to 500miles that can be powered by mature, proven sustainable power supplies: steel wheel on steel track electric trains, powered by sustainable harvested renewable power such as wind power, solar power, and both conventional and run of river hydropower.

For a corridor primarily serving trips of 200miles to 500miles, the preferable electrical passenger rail is what we call “bullet trains” or, in US Department of Transportation lingo, “Express High Speed Rail”. This takes the established 20th century technology of electric corridor rail and applies the established 20th century civil engineering design techniques behind the Interstate Highway system: express throughways, grade separated from crossing transport paths, with paths cambered for the design speed of travel.

The design speeds for HSR is not the 60mph-70mph that the Interstate Highways are designed for, but 160mph-240mph. The Express HSR system in Florida would have been one of the 160mph variety, due to the limits of an expressway median alignment, but the corridor approved in California for the San Joaquin Valley (the southern part of the Central Valley that stretches from Bakersfield just north of the LA Basin to Redding in far Northern California) will be a 21st Century 220mph+ rail corridor.

The design speeds for HSR is not the 60mph-70mph that the Interstate Highways are designed for, but 160mph-240mph. The Express HSR system in Florida would have been one of the 160mph variety, due to the limits of an expressway median alignment, but the corridor approved in California for the San Joaquin Valley (the southern part of the Central Valley that stretches from Bakersfield just north of the LA Basin to Redding in far Northern California) will be a 21st Century 220mph+ rail corridor.

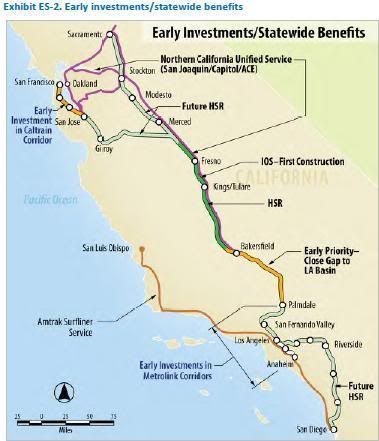

A major strength of this approach to High Speed Rail around the world is that HSR trains are physically compatible with conventional rail corridors. The California HSR Authority plans to make use of this compatibility in two ways:

- Once the full Express HSR corridor is completed between San Jose and the San Fernando Valley, the last 10mi-20mi in the south to LA Union Station and the last 55mi to the north to San Francisco’s Transbay Terminal station (presently under construction) will be completed on upgraded Metrolink and Caltrain corridors, improved to allow for the 110mph-125mph Rapid Rail speeds that have always been planned for passing through the larger urban areas; and

- Before the Initial HSR System between Merced and the San Fernando Valley is ready, the Initial Construction Segment just approved will host the existing San Joaquin service, the Amtrak corridor with the sixth highest ridership in the country.

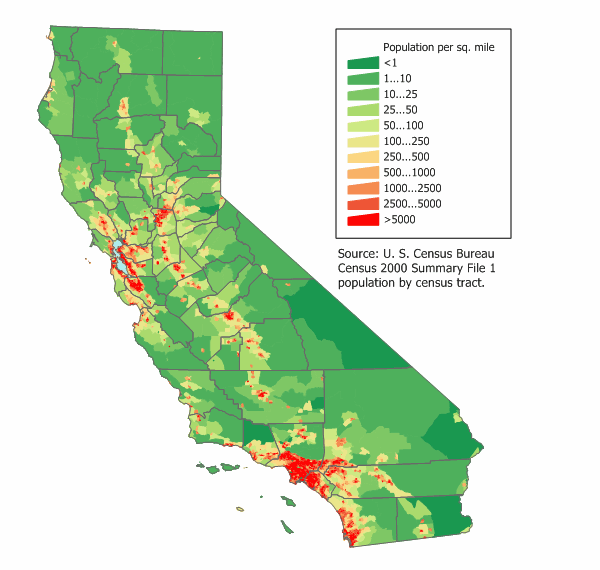

When the California HSR system is completed, it will connect the top five urbanized areas in California: LA – Long Beach; San Francisco – Oakland; San Diego; Riverside – San Bernandino; and San Jose. It will connect eight of the top ten, including Sacramento, Fresno, and Bakersfield. In short, if you want a good idea of where the HSR system is going, look at a map of the population distribution of the state. By and large, those red blotches, that’s where the HSR is going.

When the California HSR system is completed, it will connect the top five urbanized areas in California: LA – Long Beach; San Francisco – Oakland; San Diego; Riverside – San Bernandino; and San Jose. It will connect eight of the top ten, including Sacramento, Fresno, and Bakersfield. In short, if you want a good idea of where the HSR system is going, look at a map of the population distribution of the state. By and large, those red blotches, that’s where the HSR is going.

The Political Challenge

The major political challenge facing the California HSR system over the next six years is the challenge of gaining a steady source of HSR funding that is on terms and at a level of funds adequate for the needs of the California system.

Thanks to the effective strategy of the Obama administration when they allocated $8b of Stimulus II funds to High Speed Rail, California will have a lot of allies in that fight.

In the first push to build High Speed Rail in the United States, opponents of HSR arrived at the effective strategy of putting all of our HSR eggs in a single basket — the very expensive to build in Northeast Corridor. That was very politically effective, since so much of the support in the Senate came from the NEC states of Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Maryland, with additional support from Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont and Virginia, states with connecting services into the Northeast Corridor. And it ensured that the HSR program of the time, the “Acela”, would be shortchanged and hobbled, so that the top speed of 150mph would only be achieved for a few relatively short stretches of track.

However, under the $8b in ARRA HSR funding, Illinois, Michigan, Virginia and North Carolina are presently building second tier “Rapid Rail” HSR corridors, and Washington State is completing bottleneck elimination, which bring raising the speed into the Rapid Rail range onto the agenda. And the petroleum industry funded and directed Tea Party assault on rail transport is simply far more effective when fighting establishment of a new service than it is in convincing people that they don’t like a service they already have and use.

The political argument in favor of Federal funding for HSR in 2015 or 2017, in other words, is not being made by men in suits in state legislatures or the Congress. It is presently being made by people working hard to make something useful, with shovels in the ground and track being laid. As services begin taking advantage of that infrastructure, and people experience the benefit, and in particular as local Chambers of Commerce in the communities that benefit spread the word to the neighbors that do not yet have the services, the political mouthpieces will begin to take up the argument.

California will wish to direct that argument in three directions:

- Multi-tier funding for both Express and Rapid Rail HSR systems — as California and the NEC are the only qualifying HSR funding, but California and the NEC alone do not have the political weight that they do in alliance with present and prospective Rapid Rail states

- Multi-year funding — as California’s system in particular does not lend itself to a large number of incremental improvements, but rather requires expensive segments to overcome the geographical challenges of descending into the LA Basin and traversing from the Central Valley to the Bay Area to its west

- An 80:20 federal:state match or better — as ex-Gov. Schwarzenegger’s promise of a 50:50 match to land the first round of HSR funding burned through California’s state HSR bond funding of $9b far more rapidly than California can sustain

Given those three elements, the large California delegation has lots of leeway to trade votes on specific details in pursuit of a larger total annual HSR appropriation.

There are a variety of other political challenges ahead, as discussed on the California HSR blog, but working toward 2015 or 2017 HSR appropriation is the biggest political task that California needs to tackle.

The Transportation Challenges

The California HSR system is not, of course, the be-all-and-end-all of sustainable intercity transport for the State of California. While most of the largest urbanized areas are on the planned system, Phase 1 of the planned system will not be operational between SF and LA until 2028 and will not be completed until 2029 or later. That puts off the Express HSR system to Sacramento and to the Inland Empire and San Diego to the 2030’s. At the same time, not all of the urbanized areas that ought to be provided with sustainable intercity transport options lie along the California HSR system.

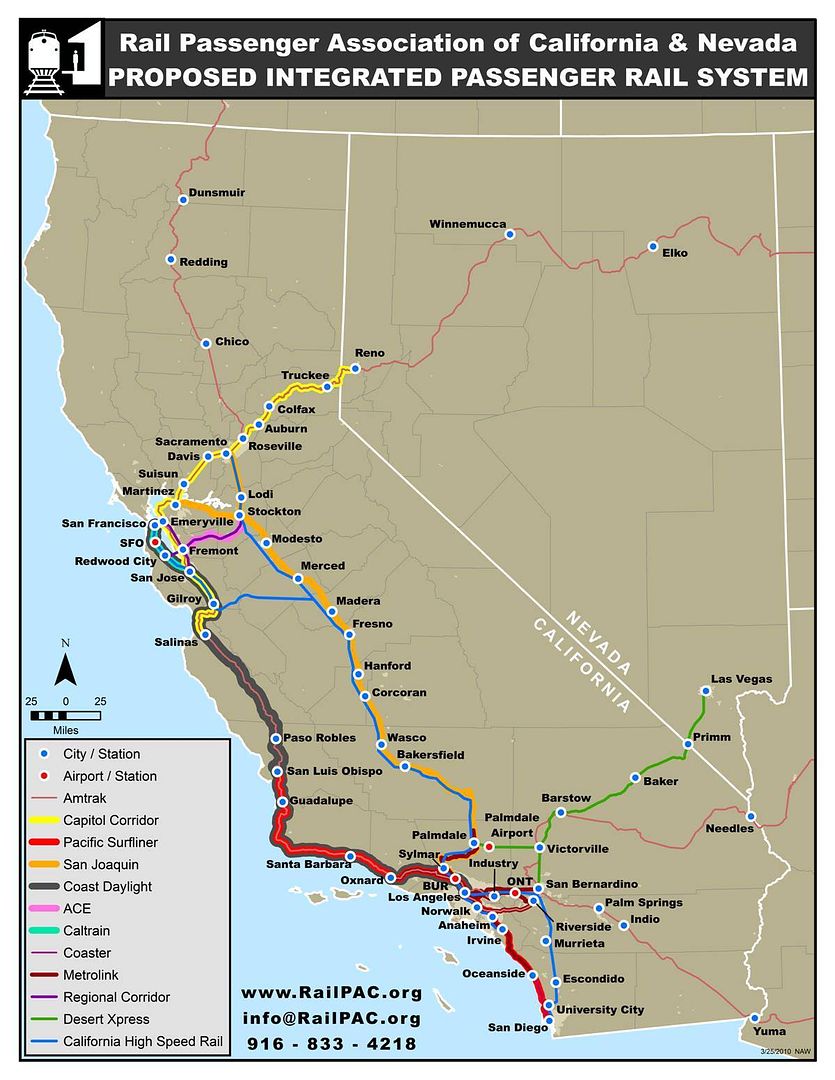

However, when you look at the existing Amtrak California corridors, added on top of the planned HSR corridors, the result is a much more complete system — and many parts of the complete system can be rolled out in advance of completion of HSR Phase 1 from SF to LA/Anaheim.

In southern California, there are already plans afoot to increase the speed along the Surfliner corridor to 110mph. This will connect to the Express HSR system at LA Union Station and at San Diego, but runs along the coast rather than along the inland route taken by the Express HSR.

In southern California, there are already plans afoot to increase the speed along the Surfliner corridor to 110mph. This will connect to the Express HSR system at LA Union Station and at San Diego, but runs along the coast rather than along the inland route taken by the Express HSR.

The Surfliner is a “corridor service”. While it runs from San Diego to Santa Barbara, with some services running through to San Lois Obispo, it is not provided to serve some massive Santa Barbara to San Diego transport market. Rather, it serves a large number of intervening trips, for the southern end of the Central Coast into the LA Basin, between points in the LA Basin and Orange County, between points in the greater San Diego area, and between the greater San Diego area and the LA Basin and Orange County.

So while the Surfliner is not oriented to longer distance intercity trips, it is oriented to longer intercity trips between and within two neighboring large metropolitan areas. And if the NEC Regionals and Acelas are treated as distinct classes of service primarily along into a single corridor, that leaves the Pacific Surfliner as the second most successful Amtrak corridor service, with nearly 3m riders per year.

If California succeeds in establishing funding for two tiers of HSR, accelerating the Surfliner to 110mph is one of the first Rapid Rail projects that California ought to be applying for. However, even better would be electrification of the corridor. This would be substantially more expensive, due to the civil engineering and likely additional tunneling required to avoid areas along the coast where a 125mph corridor represents an engineering and/or a political challenge.

Connecting the southern Central Valley to Sacramento and to the Bay Area is the San Joaquin route. This serves nearly a million riders per year, which will increase when it starts running on the Madera to Bakersfield segment of the HSR corridor in 2018. Running at 110mph on this corridor will cut about an hour off of the 6hr 15min end to end time.

Connecting the southern Central Valley to Sacramento and to the Bay Area is the San Joaquin route. This serves nearly a million riders per year, which will increase when it starts running on the Madera to Bakersfield segment of the HSR corridor in 2018. Running at 110mph on this corridor will cut about an hour off of the 6hr 15min end to end time.

Madera to Merced is slated for the Second Construction segment, and if California in cooperation with allies at the Federal level has to ratchet up Federal funding for HSR in stages, Madera to Merced is a section that could be constructed on its own as an extension of the Initial Construction Segment, before sufficient funds have been put together to fund the descent down into the San Fernando Valley. However, Merced through to Sacramento is not slated to be pursued for HSR until the 2030’s. So an upgrade to 110mph track in the current San Joaquin corridor from Merced to Sacramento, in cooperation with the Right of Way owner BNSF, would be a substantial benefit immediately, would increase the ridership of the Initial HSR Service from Merced to the LA Basin and, when Phase 2 of the Express HSR to Sacremento is completed, could continue to provide complementary service to towns served by the San Joaquin that will not have stations on the Express HSR corridor.

The second area to look for improvements on the San Joaquin is the section of track that it shares with the Capitol Corridor between Sacramento and the Bay Area. This is a section of corridor (in blue, where the Capitol Corridor runs along the east side of the North Bay) where a dedicated express track, aggressively superelevated, would both allow faster transit by the San Joaquin and Capitol Corridor trains that share the track, but also allow for more rapid freight transit on BNSF’s freight route into Oakland.

The second area to look for improvements on the San Joaquin is the section of track that it shares with the Capitol Corridor between Sacramento and the Bay Area. This is a section of corridor (in blue, where the Capitol Corridor runs along the east side of the North Bay) where a dedicated express track, aggressively superelevated, would both allow faster transit by the San Joaquin and Capitol Corridor trains that share the track, but also allow for more rapid freight transit on BNSF’s freight route into Oakland.

Between an upgrade of the Merced/Sacramento route, which the route to Oakland shares between Merced and Stockton, and an upgrade of the route shared with the Capitol Corridor between Martinez and Okland, it ought to be possible to take a further hour or more off the Bakersfield/Oakland.

The Surfliner serves the southern Central Coast, but this leaves out the central and northern Central Coast. The Rail Passenger Association of California and Nevada proposes extending the Capitol Corridor on the southern side of its route through Gilroy to Salinas, on the northern Central Coast, and on the northern side of its route through to Reno Nevada. It also proposes establishing a single Coast Daylight service from San Francisco to LA Union Station, complementing the Coast Starlight that runs from the Pacific Northwest through to LA via the same route.

The Surfliner serves the southern Central Coast, but this leaves out the central and northern Central Coast. The Rail Passenger Association of California and Nevada proposes extending the Capitol Corridor on the southern side of its route through Gilroy to Salinas, on the northern Central Coast, and on the northern side of its route through to Reno Nevada. It also proposes establishing a single Coast Daylight service from San Francisco to LA Union Station, complementing the Coast Starlight that runs from the Pacific Northwest through to LA via the same route.

The upgrade of the Coastal route requires work to expand capacity. Since most mainline freight rail corridors in the state of California are oriented to east-west transcontinental routes, the coastal route serves an important secondary freight role for freight between the LA Basin and both the Bay Area and Pacific Northwest, and does not have spare capacity to support both the slow, heavy freight traffic that it presently serves as well as an additional passenger rail service. Given the extremely slow scheduled transit speeds of the Coast Starlight (which in turn are frequently not met, leading to the nickname of “Coast Starlate”), the section between San Lois Obispo and Salinas is not a natural target for upgrade to Rapid Rail. However, if the sections between Salinas and San Jose and between Santa Barbara and LA Union station are upgraded for 110mph speed, and the section between Santa Barbara and Salinas is upgraded for greater capacity and reliability, the result will be a useful connecting service to HSR both in Burbank / LA Union Station to the south, and Gilroy / San Jose to the north.

Conclusions? Quite the Opposite: Beginnings

Naysayers will say that the California HSR line does not offer sufficient certainty. However, for certainty, we should stick to oil based intercity transport, which we can be certain will fail use sometime in the century ahead. If we are to gain the flexibility to maintain intercity transport between our large urban areas even if the supply of oil is interrupted, we have to change the way we are doing things.

With change comes uncertainty, and with uncertainty comes risk of failure — but the certainty of failure is not a step up from the risk of failure.

And further, by pursuing useful complementary connecting rail systems, California can gain substantial improvements in its ability to respond to crises in the decade that we are in, while also making progress on a sustainable intercity trunk rail system to serve the state for decades ahead.

But those are my thoughts. The end of the Midnight Oil opening act is never the last word, but only the beginning of the conversation. And a reminder that, despite what some people take away from the name, any thoughts, news, visions of sustainable transport are on topic, from walking and biking to the local grocery on up.

With that, I leave the stage to bring on the headliners.

Midnight Oil ~ Truganini

1 comments

Author