(2 pm. – promoted by ek hornbeck)

cross-posted from Voices on the Square

As a member of the WorldWide Transit Cabal (not to be confused with the Secret Worldwide Transit Cabal, since of course their membership is secret, though at times my blogging is as active as there’s), I have long argued that development of sustainable transport will be good for the economy as well as other growing things (to paraphrase the National Lampoon).

As a member of the WorldWide Transit Cabal (not to be confused with the Secret Worldwide Transit Cabal, since of course their membership is secret, though at times my blogging is as active as there’s), I have long argued that development of sustainable transport will be good for the economy as well as other growing things (to paraphrase the National Lampoon).

Recently, a study by Professor Gary Pivo has been released that demonstrates that this is not just a forward looking statement. Sustainable Transit-Oriented Development is presently good for home values and are associated with lower risk of foreclosure. How good? To quote Ped Shed’s summary of the research results:

The second hypothesis was that default risk was reduced by sustainability features (or conversely, risk was increased by unsustainable features). This also turned out to be true. The effect of the variables was substantial:

- Commute time: Every 10-minute increase in average commute time increased the risk of default by 45%.

- Rail commute: Where at least 30% of the residents took a subway or elevated train to work, the risk of default decreased by 64.4%. New York City was omitted from this calculation because it skewed the results.

- Walk commute: Every increase of 5 percentage points in the percent of residents who walk to work decreased the risk of default by 15%.

- Retail presence: Where there were at least 16 retail establishments nearby, the risk of default decreased by 34.4%.

- Affordability: For properties with some units required to be affordable, the risk of default decreased by 61.9%.

- Freeway presence: Where properties were located within 1,000 feet of a freeway, the risk of default increased by 59%.

- Park presence: Where properties were located within 1 mile of a protected area, the risk of default decreased by 32.5%.

And this does not seem to be just “fishing for results”: adding these factors to a model used by other researchers, including “characteristics of the loan, property, neighborhood and location, and regional and national economies” improved the accuracy of the model on four measures of goodness of fit.

The challenge of location and the Suburban Retrofit strategy

I’ve written of Suburban Retrofit before, most recently July last year in Sunday Train: Rescuing the Exurb from its Design. As I said then,

[O]ver the past thirty years, we built a whole lot of residences in the outer suburbs and the exurbs. Are we going to allow them to become slums?

Remember that slums are not an intrinisically urban phenomenon. Our association of slums with the inner urban areas of large cities is a historical consequence of the same shift to the suburbs that seems to have come to an end with the end of cheap gas and the collapse of the housing bubble. However, what makes an area a slum is quite general: you get a slum when the value of the properties fall below the replacement cost.

That is the silent threat looming over Outer Suburban and Exurban properties. If property values drop below replacement cost, then the rational financial response is to find the activity with the best positive cash flow, and to extra value from the property while allowing the property to run down. Which is to say, when property values drop below replacement cost, the financially sensible thing to do for the property owner is to act as a slumlord. Of course, no every property owner wishes to become a slumlord, but as properties in an area are allowed to run down, further eroding the value of all properties in that area, there is a growing incentive to sell out to someone who is willing to be a slumlord.

This recent research only confirms that. Turn the positive factors for sustainable transit around, and the model results are that: every 5% decrease in percentage of residents who walk to work increases risk of default by 15%; failing to have 30% of residents take a train to work increases default risk by 64.4%; failing to have at least 16 retail establishments nearby increases default risk by 34.3%; failing to have properties designed to be affordable increases default risk by 61.9%; and failing to have a protected area (aka “park”) within a mile increases default risk by 32.5%.

These are all things that can be addressed in place in a conventional suburban development by the establishment of a dedicated public transport corridor passing through or next to retrofitted Suburban Villages. The suburban villages are permitted to be developed by allowing denser and taller mixed-use retail, office and residential development in a quarter mile radius around the priority stop on the dedicated transport corridor.

Investment to upgrade the walkability of the neighborhoods within a mile radius of the Suburban Village, with well designed sidewalks on both sides of the street, proper cut-outs, traffic calming on side streets and safe traffic crossings on main streets extends the walkable district to 16 times the area of the Suburban Village itself.

Investment in the bikeability of the neighborhoods within a three mile radius of the Suburban Village, with traffic calming on alternative routes shared with bicycles and automatic traffic signal detectors that can detect a bike waiting on a light, extends the bikeable district to 144 times the area of the suburban village itself.

Investment in the bikeability of the neighborhoods within a three mile radius of the Suburban Village, with traffic calming on alternative routes shared with bicycles and automatic traffic signal detectors that can detect a bike waiting on a light, extends the bikeable district to 144 times the area of the suburban village itself.

The traffic calming on alternative routes to the Suburban Village makes it possible for a network of 35mph streets to connect to the Suburban Village. That makes it possible for neighborhood electric vehicles to access the suburban village. Whereas the mainstream development of electric cars has been focused on Interstate Highway capable vehicles to act as a more expensive drop-in replacement for our current gasoline powered cars, there has been at the same time development of neighborhood electric vehicles that can be both less expensive to operate and less expensive to purchase than a new gasoline powered car. These typically have a top speed of about 30mph, and typically are allowed to be used on the public right of way with a speed limit of 35mph or lower … and 35mph or less, reinforced as the actual traffic speed by traffic calming measures, is also a reasonable speed limit target for shared use bicycle boulevards.

This is the leverage provided by the Suburban Village approach: each Suburban Village converts a much large area of suburban development into an area where it becomes possible for Active Transport and neighborhood electric vehicles to either supplement or replace reliance on the automobile for transport.

The Challenge of the Cul-de-Sac

In many suburban areas, not only is there heavy reliance on higher speed main road routes connecting individual neighborhoods, but alternative road routes actually do not exist. Instead there is a side street off of the main thoroughfare, which then divides to connect into a collection of cul-de-sacs. Any route that actually runs through the neighborhood is circuitous by design, in order to discourage cars from using it as an alternative route.

In many suburban areas, not only is there heavy reliance on higher speed main road routes connecting individual neighborhoods, but alternative road routes actually do not exist. Instead there is a side street off of the main thoroughfare, which then divides to connect into a collection of cul-de-sacs. Any route that actually runs through the neighborhood is circuitous by design, in order to discourage cars from using it as an alternative route.

What is to be done to improve bikeability and allow for the use of neighborhood electric vehicles in this kind of landscape, where the traditional small town street grid has been replaced by a branching network of cul-de-sacs?

This is a question raised at the Suburban Retrofit page at the Useful Community Development site:

When you have cul de sacs and lots of them, how do you re-establish a grid? It’s very difficult as long as the housing market is robust, all homes are occupied, and all business areas are viable. But that’s hardly the case in many neighborhoods across America.

In simplest terms, cul de sacs are reconnected to one another, and therefore to redundant systems of access to destinations, by having one lot or part of one lot near the end of the cul de sac be appropriated for a street connecting to a nearby street.

That could become more practical than it sounds in view of the foreclosure situation in some communities. If you can do it, start there. Just one connection between two subdivisions that formerly were cut off from one another is worthwhile, particularly if both have access to a different collector street.

One of the factors in Gary Pivo’s study reinforces one advantage of this approach. If an entire abandoned lot is taken to form a cul-de-sac bridge, that means that there is also land that can be used to provide a local “pocket park” park for the area. And traffic calming measures that can maintain traffic at 35mph or 20mph to form an effective bicycle boulevard also replaces the safeguard against high speed traffic roaring through the neighborhood that the cul-de-sac development originally provided.

But WHAT Public Transport System

This strategy is anchored by a priority stop on a dedicated transport corridor on a public transport system. So the question might arise … isn’t that a little vague?

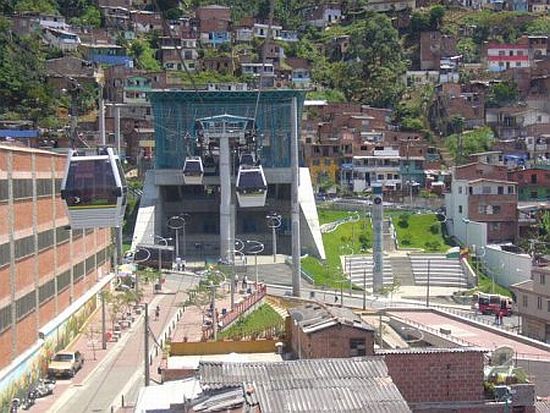

It is indeed vague, and intentionally so. The strategy is quite mode agnostic. The dedicated transport corridor could be a regional rail network connecting the suburb to the closest large urban center. It could be a light rail or “rapid streetcar” line operating in its own right of way in this area. It could be a local rail line taking advantage of a lightly used or unused freight branch line. It could be a busway for a trolleybus. It could, indeed, be a mix of these, with the priority stop being an interchange between two public transport routes, or with a dedicated streetcar lane also available to be used as an express busway. Heck, if solar-power-assisted cable cars (pictured, right) meet a particular need in a local area, then solar-power-assisted cable cars.

It is indeed vague, and intentionally so. The strategy is quite mode agnostic. The dedicated transport corridor could be a regional rail network connecting the suburb to the closest large urban center. It could be a light rail or “rapid streetcar” line operating in its own right of way in this area. It could be a local rail line taking advantage of a lightly used or unused freight branch line. It could be a busway for a trolleybus. It could, indeed, be a mix of these, with the priority stop being an interchange between two public transport routes, or with a dedicated streetcar lane also available to be used as an express busway. Heck, if solar-power-assisted cable cars (pictured, right) meet a particular need in a local area, then solar-power-assisted cable cars.

What the strategy is aiming at is an effective public transport system that does not get bogged down in traffic on the main road arteries. How that is accomplished depends heavily on local circumstances, including the legacy road and rail rights of way. Each mode of transport has its own advantages and disadvantages, and what works well in one community can easily fail completely in another.

After all, our current automobile-dependent transport system depends heavily on the idea that there can be a one size fits all transport system that can be all things to all people. However, one-size-fits-all never fits everyone, and typically fits the majority of people badly.

This is, indeed, one of the challenges facing Suburban Retrofit. As with all redevelopment, it requires intelligent study of the details of the local community where the retrofit is taking place. It also requires serious discussion with, and respect for the views of, the members of the local community who are the legacy stakeholders. Neither of these is required in greenfield cookie-cutter property development.

The flipside is that the Suburban Retrofit offers the prospect of a community redevelopment that is actually sustainable over the coming century, which is something no greenfield cookie-cutter development process can offer.

This is one of the benefits of Gary Pivo’s study. When proposing a Suburban Retrofit that will improve the sustainability of an area, we can get local real estate agents, property developers, and banks on board with the real financial benefits that sustainable transit-oriented development can provide. This will become even easier if there is implementation of Gary Pivo’s proposal regarding how to make use of his results. From Ped Shed again:

A great advantage of the sustainability variables in this study is that all are based on existing datasets provided by the Census Bureau and other agencies. According to Pivo, “it would be relatively easy to build an online address-based lookup tool that any lender can use to obtain certain sustainability information on a given property.” Furthermore, because sustainability factors reduce default risk, the lender can give a property more favorable loans without increasing its risk exposure. Pivo suggests an online tool could provide the recommended loan adjustments for any given property.

Consideration and Contemplation

I of course encourage discussion, questions and additional links or videos related to the topic in this week’s Sunday Train.

However, also feel free to use the comment section of this essay to raise any issue regarding sustainable transport or sustainable energy.

2 comments

Author