(6 PM – promoted by TMC)

This diary was posted on October 29, 2010 by Ria D who passed through the veil too soon. Blessed Be.

when the veils grow thin….

by: RiaD

Fri Oct 29, 2010 at 17:04:50 PM EDT

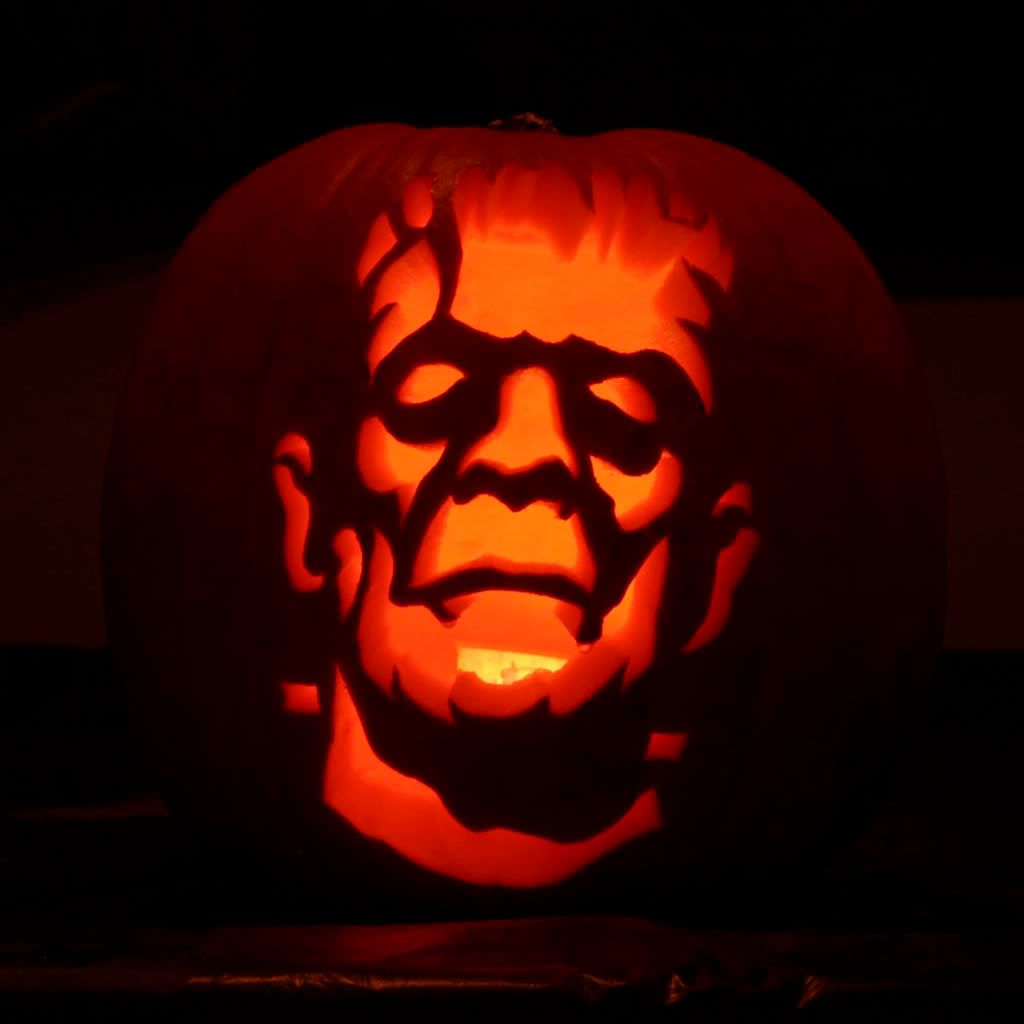

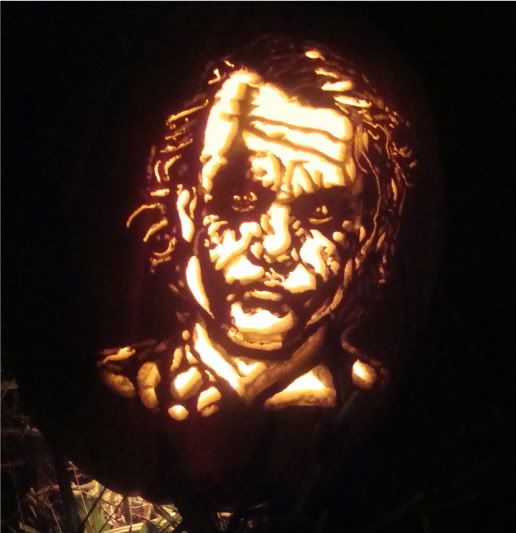

(all pictures are of carved pumpkins & may be clicked on to see larger)

Sunday is Hallowe’en, a night for children to dress up & go Trick-or-Treating.

But this holiday has its origins waaaay back, back before the written word, in pagan times.

In ancient Ireland Samhain has great importance.

The Ulster Cycle is peppered with references to Samhain. Many of the adventures and campaigns undertaken by the characters therein begin at the Samhain Night feast. One such tale is Echtra Nerai (‘The Adventure of Nera’) concerning one Nera from Connacht who undergoes a test of bravery put forth by King Ailill. The prize is the king’s own gold-hilted sword. The terms hold that a man must leave the warmth and safety of the hall and pass through the night to a gallows where two prisoners had been hanged the day before, tie a twig around one man’s ankle, and return. Others had been thwarted by the demons and spirits that harassed them as they attempted the task, quickly coming back to Ailill’s hall in shame. Nera goes on to complete the task and eventually infiltrates the sídhe where he remains trapped until next Samhain. Taking etymology into consideration, it is interesting to note that the word for summer expressed in the Echtra Nerai is samraid.

The other cycles feature Samhain as well. The Cath Maige Tuireadh (Battle of Mag Tuired) takes place on Samhain. The deities Morrígan and Dagda meet and have sex before the battle against the Fomorians; in this way the Morrígan acts as a sovereignty figure and gives the victory to The Dagda’s people, the Tuatha Dé Danann.

The tale The Boyhood Deeds of Fionn includes an important scene at Samhain. The young Fionn Mac Cumhail visits Tara where Aillen the Burner, one of the Tuatha Dé Danann, puts everyone to sleep at Samhain and burns the place. Through his ingenuity Fionn is able to stay awake and slays Aillen, and is given his rightful place as head of the fianna.

For a very readable novel based on the Ulster Cycle i suggest reading Red Branch by Morgan Llywelyn.

If you like this time period some other wonderful books by Llywelyn are Finn Mac Cool; Bard; Druids and Brian Boru.

Another wonderful Celtic Myth is The Mabinogion Tetrralogy by Evangeline Walton which brings together the four books of the Mabinogion Cycle: Prince of Annwn, The Children of Llyr, The Song of Rhiannon and The Island of the Mighty.

Todays Hallowe’en is a mash-up of catholic, roman & celtic rituals/holidays.

In the Roman Catholic church, All Souls Day is a day commemorating all the Christians believed to be in purgatory. Celebrated on November 2, it was first established by Odilo (d. 1049), abbot of Cluny, in the 11th century, and it was widely celebrated by the 13th century. The date follows All Saints’ Day, with the idea that remembering the saints in heaven should be followed by remembering the souls awaiting release from purgatory. Roman Catholic doctrine holds that the prayers of the faithful on earth will help cleanse these souls in order to prepare them for heaven. All Hallows Eve is the day before All Saints Day is spent in preparation for the holy day and praying for the dead. All Hallows Eve preceeds these two Holy days.

Halloween is All-Hallows’-Eve which is the night-before-All-Saints’- Day. Some tell me they understand that Halloween pranks were a post-Reformation contribution to plague Catholics who kept the vigil of All Saints. Now it is possible that Halloween was abused for such a purpose; nevertheless, during all the Christian centuries up until the simplification of the Church calendar in 1956, it was a liturgical vigil in its own right and thus has a reason for being.

Whether the Church “baptized” the customs of the Celts & Romans or chose this season for her feasts of the dead independent of them, their coincidence shows again how alike men are.

It was in the eighth century that the Church appointed a special date for the feast of All Saints, followed by a day in honor of her soon-to-be saints, the feast of All Souls. She chose this time of year, it is supposed, because in her part of the world it was the time of barrenness on the earth. The harvest was in, the summer done, the world brown and drab and mindful of death. Snow had not yet descended to comfort and hide the bony trees or blackened fields; so with little effort man could look about and see a meditation on death and life hereafter.

Apparently how you spent the vigil of All Saints depended on where you lived in Christendom. In Brittany the night was solemn and without a trace of merriment. On their “night of the dead” and for forty-eight hours thereafter, the Bretons believed the poor souls were liberated from Purgatory and were free to visit their old homes. The vigil for the souls, as well as the saints, had to be kept on this night because of course the two days were consecutive feasts – and a vigil is never kept on a feast.

Breton families prayed by their beloveds’ graves during the day, attended church for “black vespers” in the evening and in some parishes proceeded thence to the charnel house in the cemetery to pray by the bones of those not yet buried or for whom no room could be found in the cemetery. Here they sang hymns to call on all Christians to pray for the dead and, speaking for the dead, they asked prayers and more prayers.

Late in the evening in the country parishes, after supper was over, the housewives would spread a clean cloth on the table, set out pancakes, curds, and cider. And after the fire was banked and chairs set round the table for the returning loved ones, the family would recite the De Profundis (Psalm 129) again and go to bed. During the night a townsman would go about the streets ringing a bell to warn them that it was unwise to roam abroad at the time of returning souls.

It was in Ireland and Scotland and England that All Hallows’ Eve became a combination of prayer and merriment. Following the break with the Holy See, Queen Elizabeth forbade all observances connected with All Souls’ Day. In spite of her laws, however, customs survived; even Shakespeare in his Two Gentlemen of Verona has Speed tell Valentine that he knows he is in love because he has learned to speak “puling like a beggar at Hallowmas.” This line must have escaped the Queen.

The Roman version of Samhain was called Feralia and was observed on February 21. It was the public honoring of the manes, or spirits of the dead, which began with the private ceremonies of the Parentalia. Offerings of food were made at tombs by family members.

During Feralia, ancient Romans would travel to the tombs of their ancestors (called “Manes”), bringing offerings of wreathes, grain, salt, and bread soaked in wine; violets would be scattered around and in the tombs. The wealthy families of Rome would prepare lavish public feasts at the tombs.

Unlike the rousing celebration of Day of the Dead, Feralia was considered a time of mourning. Marriages were banned during this time and public worship of the Gods was stopped; no incense was burned on the altars and hearth fires were often left unlit. One ancient story tells of a time when Fernalia was ignored during war time, causing spirits to rise from their graves and haunt the streets of Rome until tribute was made properly to the spirits in their tombs.

Samhain is the winter season of the ancient Celts.

The Celtic year began in November, with Samhain. The Celts were influenced principally by the lunar and stellar cycles which governed the agricultural year – beginning and ending in autumn when the crops have been harvested and the soil is prepared for the winter.Samhain Eve, in Erse, Oidhche Shamhna, is one of the principal festivals of the Celtic calendar, and is thought to fall on or around the 31st of October.

ike most Celtic festivals, it was celebrated on a number of levels. Materially speaking it was the time of gathering food for the long winter months ahead, bringing people and their livestock in to their winter quarters. To be alone and missing at this dangerous time was to expose yourself and your spirit to the perils of imminent winter. From the point of view of a tribal people for whom a bad season meant facing a long winter of famine in which many would not survive to the spring, it was paramount.

Samhain was also a time for contemplation. Death was never very far away, yet to die was not the tragedy it is in modern times. Of signal importance to the Celts people was to die with honour and to live in the memory of the tribe and be honoured at the great feast (in Ireland this would have been the Fleadh nan Mairbh (Feast of the Dead)) which took place on Samhain Eve.

This was the most magical time of the year; Samhain was the day which did not exist. During the night the great shield of Skathach was lowered, allowing the barriers between the worlds to fade and the forces of chaos to invade the realms of order, the material world conjoining with the world of the dead. At this time the spirits of the dead and those yet to be born walked amongst the living. The dead could return to the places where they had lived and food and entertainment were provided in their honour. In this way the tribes were at one with its past, present and future. This aspect of the festival was never totally subdued by Christianity.

Samhain marked the end of the harvest, the end of the “lighter half” of the year and beginning of the “darker half”. It was traditionally celebrated over the course of several days. Many scholars believe that it was the beginning of the Celtic year. It has some elements of a festival of the dead. The Gaels believed that the border, the veil between this world and the otherworld became thin on Samhain; because some animals and plants were dying, it thus allowed the dead to reach back through the veil that separated them from the living.

some more on samhain in video form….

So what of these Hallowe’en traditions we celebrate, where do they come from?

Bonfires played a large part in the festivities celebrated down through the last several centuries, and up through the present day in some rural areas of the Celtic nations and the diaspora. Villagers were said to have cast the bones of the slaughtered cattle upon the flames. In the pre-Christian Gaelic world, cattle were the primary unit of currency and the center of agricultural and pastoral life. Samhain was the traditional time for slaughter, for preparing stores of meat and grain to last through the coming winter.

With the bonfire ablaze, the villagers extinguished all other fires. Each family then solemnly lit its hearth from the common flame, thus bonding the families of the village together. Often two bonfires would be built side by side, and the people would walk between the fires as a ritual of purification. Sometimes the cattle and other livestock would be driven between the fires, as well.

Costumes and Masks worn by the Gaels, was an attempt to copy the evil spirits or placate them. In Scotland the dead were impersonated by young men with masked, veiled or blackened faces, dressed in white.

Candle lanterns (Gaelic: samhnag), carved from turnips were part of the traditional festival. Large turnips were hollowed out, carved with faces, placed in windows to ward off evil spirits.

Guisers – men in disguise, were prevalent in 16th century in the Scottish countryside. Children going door to door “guising” (or “Galoshin” on the south bank of the lower Clyde) in costumes and masks carrying turnip lanterns, offering entertainment of various sorts in return for food or coins, was traditional in 19th century, and continued well into 20th century. At the time of mass transatlantic Irish and Scottish immigration that popularized Halloween in North America, Halloween in Ireland and Scotland had a strong tradition of guising and pranks.

Divination, or fortune-telling, is a common folkloric practice that has also survived in rural areas. The most common uses were to determine the identity of one’s future spouse, the location of one’s future home, and how many children a person might have. Seasonal foods such as apples and nuts were often employed in these rituals. Apples were peeled, the peel tossed over the shoulder, and its shape examined to see if it formed the first letter of the future spouse’s name. Nuts were roasted on the hearth and their movements interpreted – if the nuts stayed together, so would the couple. Egg whites were dropped in a glass of water, and the shapes foretold the number of future children. Children would also chase crows and divine some of these things from how many birds appeared or the direction the birds flew.

2 comments

Author

I miss her.