(2 pm. – promoted by ek hornbeck)

The headlines out of California indicate that there has been a substantial shift in terms of the California HSR system. In particular, it seems that Gov. Brown has waded into the fray and is reframing the issue from the Only-An-Infrastructure-Geek-Could-Love frame of the Initial Construction Segment and the mythical “Train to Nowhere”, to the “when do I get to ride it?” frame of the Initial Operating Service.

The headlines out of California indicate that there has been a substantial shift in terms of the California HSR system. In particular, it seems that Gov. Brown has waded into the fray and is reframing the issue from the Only-An-Infrastructure-Geek-Could-Love frame of the Initial Construction Segment and the mythical “Train to Nowhere”, to the “when do I get to ride it?” frame of the Initial Operating Service.

You can find the lead up to the big move at the CHSRblog:

Deal Reached to Combine Caltrain Electrification and HSR (22MAR)

Legislature Appears to Have Votes to Approve HSR Funding (23MAR)

Jerry Brown Lowers HSR Cost by $30 billion

And Newspaper sneak previews of what will be Monday’s Big News at:

Sacramento Bee: Gov. Jerry Brown to change high-speed rail plan, lower cost by $30

Mercury News: Questions remain despite revised Calif. rail plan

SF Chronicle: High-speed rail plan slashes costs to calm critics

However, while the newspaper accounts given glimpses and hints and quotes of very carefully written statements from the principle actors … digging into the details will have to wait until the details are released.

So instead, I want to take a look at the existing “Slow Speed Rail” systems of Northern California, to get a better background understanding of what “connecting with” the existing systems might mean.

First, an Inventory of the Rail Corridors

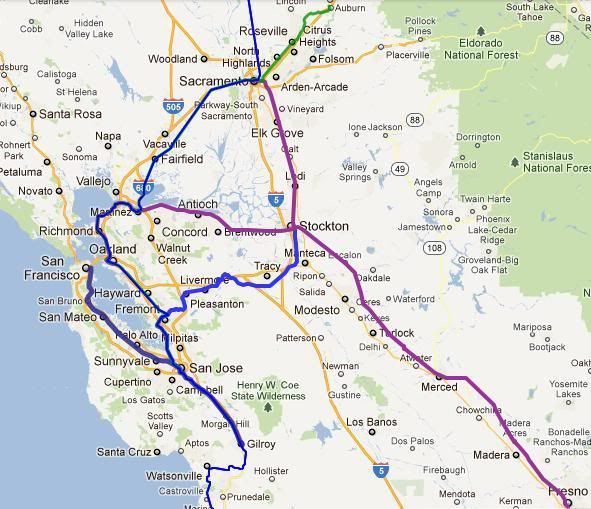

One Northern California Amtrak-California rail corridor is the San Joaquin (in purple), which runs four times a day from Bakersfield to Oakland and twice a day from Bakersfield to Sacramento ~ on the southern side, a a bus completes the trip to LA, while at the northern side, when the train runs to Oakland there is a connecting bus to Sacramento, and when the train runs to Sacramento there is a connecting bus to Oakland. The sections from Fresno on North are shown.

One Northern California Amtrak-California rail corridor is the San Joaquin (in purple), which runs four times a day from Bakersfield to Oakland and twice a day from Bakersfield to Sacramento ~ on the southern side, a a bus completes the trip to LA, while at the northern side, when the train runs to Oakland there is a connecting bus to Sacramento, and when the train runs to Sacramento there is a connecting bus to Oakland. The sections from Fresno on North are shown.

A second Northern California Amtrak-California rail corridor is the Capitol Corridor, which runs from San Jose along the eastern side of the Bay through Oakland and then across the Sacramento River to Sacramento. Most of the Capital Corridor is shared with the Amtrak service that connects northern and southern California, the Coast Starlight, which continues north from Sacramento toward the Pacific Northwest, and south from San Jose along the Central Coast to Santa Barbara and then Los Angeles, connecting to the Surfliner at LA’s Union Station (“LA-US”). The Coast Starlight is the slender blue line running from top to bottom (the Capital Corridor is actually in Green, but only the Sacramento/Auburn section peaks out from underneath the various overlaying lines).

The third intercity service runs from Stockton is the Altamont Corridor Express (in an only slightly lighter blue (oops)), running from Stockton through Tracy, Livermore and Pleasanton to Fremont and San Jose. It is a classic “commuter” rail service, with three inbound services in the morning and three outbound services in the evening.

Much of the local rail in the Bay area is BART, which is a wide-gauge third rail electric mass transit system that is not directly compatible with shared operation with an overhead electric standard gauge system like the California HSR system. However the Caltrain system (dark blue) is a local diesel standard rail system that runs from San Jose to San Francisco, with occasional extended service to Gilroy. Caltrain has long had a plan to electrify the corridor and to run trains into the train station at the basement of the new TransBay Terminal. Indeed, the first strong indication that something was moving on California HSR was the announcement of a deal to fund electrification of the Caltrain Corridor from San Jose to San Francisco.

OK, those are trains ~ why do you call them slow?

I am only being slightly wry in calling these the “Slow Trains of Northern California”. They are definitely faster than cycling, or than traveling by horseback … but if you are in a real hurry, and have a car, its possible that you will not take the train.

Consider the following schedule times, compared to what Google Maps says is the equivalent Driving time:

| Trip | Corridor | Rail Transit | Google Driving |

| Fresno / Oakland | San Joaquin | 4hrs 5min | 3hrs 5min |

| San Jose / Sacramento | Capitol Corridor | 3hrs 10min | 2hrs 12 min |

| Stockton / San Jose | ACE | 2hrs 10min | 1hr 22min |

| San Jose / San Francisco | Caltrain | 59mins / 1hr 20mins | 52mins (Sunday) |

Its only with the “Baby Bullet” Caltrain service and urban driving conditions that the train is time-competitive with driving. For intercity trips, its slower.

So, why are these trains “so slow”? Lets take a closer look at the Capitol Corridor. What I have in the following table is the Station to Station track mileage, track mile per hour, “line of sight” mileage (LOS), and “line of sight” mph (LOS mph), together with an approximate layout efficiency in terms of the LOS mileage relative to the track mileage.

So, why are these trains “so slow”? Lets take a closer look at the Capitol Corridor. What I have in the following table is the Station to Station track mileage, track mile per hour, “line of sight” mileage (LOS), and “line of sight” mph (LOS mph), together with an approximate layout efficiency in terms of the LOS mileage relative to the track mileage.

Note that the layout efficiency is “micro” efficiency. In other words, making a beeline to go to a location that there is no real point in serving gets scored as 100%, so the LOS mileage is station to station, not end to end.

Also note that the track mileage comes from the timetable, which means the track mileage is only +/- half a mile ~ where the “layout efficiency” says 100%, it probably really means something like 95%.

| Station | Mileage | mph | LOS | LOS mph | efficiency |

| Sacramento | — | — | — | — | — |

| Davis | 14mi | 56mph | 13 | 52mph | 93% |

| Fairfield | 26mi | 65mph | 26 | 65mph | 100% |

| Martinez | 18mi | 51mph | 13.5 | 39mph | 75% |

| Richmond | 19mi | 46mph | 13mi | 31mph | 68% |

| Berkeley | 6mi | 51mph | 5.5mi | 47mph | 92% |

| Emeryville | 2mi | 20mph | 2mi | 20mph | 100% |

| Oakland Jack London | 5mi | 23mph | 3.5mi | 16mph | 70% |

| Oakland Coliseum | 5mi | 23mph | 5mi | 23mph | 100% |

| Hayward | 8mi | 44mph | 8mi | 44mph | 100% |

| Fremont | 12mi | 45mph | 9mi | 34mph | 75% |

| Great America | 11mi | 39mph | 10mi | 35mph | 91% |

| San Jose | 7mi | 18mph | 6mi | 15mph | 86% |

| Sac-SJ | 133mi | 42mph | 115mi | 36mph | 86% |

Coming north to south, I start out going at a reasonable clip. Nowhere near as fast as my kid would go on the freeway (assumed that there is no highway congestion or State Highway Patrols to slow things down) … but not all that slow, either, even on LOS mph, through Davis and Fairfield, where the train maintains a good speed and the point to point layout efficiency is good. The speed stays up around 50mph to Martinez, but it loses efficiency compared to the freeway that takes a more direct bridge further west.

Then between Martinez and Richmond, the train is taking a “water line”, hugging the coast to avoid hill climbing, and between slowing down to 46mph along the track, and the layout only having a 75% efficiency Martinez/Richmond, the LOS mph drops to 31mph. This is a key slowdown, since at Richmond you can transfer to a BART train that runs under the water through downtown San Francisco.

Things slow down still more when we pass Berkely and the rail corridor starts threading its way through Oakland. Then the Capitol Corridor runs along the East Bay, with much of the drop in speed due to the slow down to the station stop, stop for passengers to entrain and detrain, and then acceleration again to head to the next stop.

The Elephant in the Room is that a lot of the destinations and a lot of the origins are on the other side of the Bay, which means either taking a bus over the Bay Bridge to San Francisco or catching a BART underneath the Bay.

Is There Anything That Can Be Done To Speed This Up!?

It requires a mental shifting of gears to go between thinking about HSR Bullet Train corridors and thinking about speeding up a corridor like this. When thinking in terms of 220mph bullet train corridors, the kinds of things that might be done to “speed this up” are things that have $100m and $1b type price tags ~ and in addition to their sticker shock will often generate furious local opposition:

- Ease the turns in the rail corridor at and north of Fairfield, other taking the required land or running a viaduct over

- Put in a new connector to Vallejo, add a rail bridge alongside the brudge used by the I-80, and run along the I-80 alignment to north of Berkeley

- Put in a new Bay rail tunnel for standard gauge trains, running to downtown SF and then joining the Caltrain corridor

- Upgrade the Caltrain corridor to four tracks wide all the way to San Jose, with 110mph~125mph Electric Passenger Express tracks for the intercity trains

Now, do that, sure, it’d be awfully fast. But given the headaches California is going through running a Bullet Train corridor from the second largest urban area in the country to the twelfth largest, at a spacing that ensures that a well built HSR Bullet Train corridor will be a slam dunk success in terms of US intercity passenger rail, not only covering its operating cost but generating a healthy surplus on top … a separate Bay/Sacramento Bullet Train is not going to be built in this decade.

What about at a more modest scale, though? After all, Ohio was proposing a corridor from Cleveland to Columbus to Cincinnati that would be much slower than the California HSR ~ but substantially faster than the above, and at a price tag closer to $1b altogether. And that was for starting a rail service from scratch, where this is an already operating service with eight trains per day each way.

The stretch of the corridor between the Sacramento River and Davis would seem ideal to upgrade the operating speed to 110mph. This requires upgrading the class of track, in cooperation with the Right of Way owner, and upgrading level crossings to 110mph class crossings. It requires installation of Positive Train Control signal systems ~ although this is scheduled to be required on all shared passenger rail corridor, its been a long standing requirement for any rail speed limit about 79mph.

There are a couple of curves that would require a train to slow down for, and the faster the top speed, the more potential speed is lost in slowing down to 40mph or 30mph to go around a curve ~ but using the tilt-train style passenger cars used on the Cascades Corridor in the Pacific Northwest would allow the speed limits to be raised for the passenger rail service.

The focus of new track would be in the coast hugging section between Martinez and Richmond. The benefit of a dedicated Express Track in this section is that, first, it can short some of these curves by “cheating” on the inside of the curve. While slow freight trains hauling bulk freight may require a 1% slope (“1:100”), an intercity passenger train can cope with a 2.5% slope (“1:40”). At the same time as curves are eased where possible, the track can be banked to allow trains to run through at a higher speed. And then if its possible to maintain 50mph or better along the Express track, the tilt train mechanism can be used to further increase the speed that the train can go through curves.

As far as expensive upgrades to speed the train through the East Bay, there could well be something that can be done at Jack London Square, where the Amtrak runs down road “streetcar style”. However, a principle opportunity to shave a few minutes off transit in this part of the Capitol Corridor is further south. BART is coming to San Jose, and with the arrival of BART, it would make sense to have the Capitol Corridor act more like an Express and skip the Hayworth Station, through an area served by multiple BART stops.

Now, suppose that this succeeds in raising the track mph to 70mph Sacramento/Davis, 80mph Davis/Fairfield, 70mph Fairfield/Martinez, 60mph Martinez/Richmond, and 65mph Oakland Coliseum / Fremont.

The saving seems modest on my end to end trip: Sacramento / San Jose has dropped by 20 minutes from 3:10 to 2:50, for a trip that is reckoned to be 2:12 by Google Maps. However, for the urban trip from Sacramento to Oakland, Jack London Square, Google figures the driving time is 1:32 in Sunday evening traffic, while the our notional rail schedule is 1:33.

What appears to be the slowest section in the table is the Berkeley / Emeryville leg, but that is primarily due to the penalty of two stations 2 miles apart. What looks like the slowest transit is Emeryville to Jack London Square. A grade separation that allows the section between Emeryville and Jack London Square to be traveled at a track speed of 33mph (including station stops) would save five minutes.

The nature of these kind of incremental upgrades is that you keep taking bites out of the transit time. The next step in the incremental upgrade is electrifying the corridor, improving acceleration out of each station, and improving acceleration out of each curve. Electrification supports adoption of active tilt-train technology. If combined with a grade separation of the train at Jack London Square, another twenty minutes might be available, bringing the transit to 2:30.

How does this fit in with the California HSR, Again?

Oh, yeah, the new California HSR system … wasn’t that the topic?

Well, it has kind of been the topic all along. A key quote from the Mercury News article:

The updated business plan also devotes up to $2 billion to improve existing urban rail. Linking with those systems rather than pushing the high-speed rail line into California’s major cities is one of the biggest cost-savers in the new plan.

“We are not sitting here saying that we ‘saved’ $30 billion,” rail authority chairman Dan Richard said Saturday. By using existing railroad rights of way, he said, “We can deliver high-speed rail, as the voters voted for it, for $30 billion less than if we had to build our own system the entire length of the way.”

Now, I haven’t seen a map of the proposed Initial Operating Service, but one way to go about this would be to electrify the Metrolink Antelope Valley line from Burbank to its terminus in Lancaster (north of Palmdale), then construct the Express HSR corridor from Lancaster to Merced. From there, hook up a locomotive on both ends (both because it needs power and to get compliance with Federal Railway Authority regulations on crash resistance on lines shared with heavy freight trains), and run along the San Joaquin route to Stockton, then west to Martinez, then along the Capital Corridor to Jack London Square.

Aha! … those who plowed through the blog above will have recognized some of those. If the Initial Operating Service were to run like this, any improvements along the Capitol Corridor between Martinez and Jack London Square would be shared by the loco-hauled temporary version of the HSR route. And while the San Joaquin route is not faster then driving from Oakland to Fresno … if you hit Merced and then crank the speed up to 220mph, the result can be appreciably faster than driving to LA ~ with the benefit, of course, of not having to drive.

Just adding the notional HSR schedule from Merced to Palmdale to the Metrolink Express time LA-US to Lancaster and the San Joaquin schedule Merced to Oakland gives a six hour trip. That is a six hour drive “in current traffic”, and of course today is Sunday. The time under weekday mid-day traffic conditions is going to rise from there. If the Metrolink corridor is electrified, with strategic Express passing track, the speed limit raised on the regular rail corridor between Merced and Stockton, and the above improvements are included, saving 0:30 to 1:00 off of that to bring the time down to 5-5½hrs.

If the next stage adds the proposed link to San Jose, and there is enough of a start on the “blended option” improvements on both sides to allow running from LA-US to SF TransBay Terminal, that jumps down to 3:45 or less. Then with completion of a Bullet Train corridor from Lancaster in the Antelope Valley down to Sylmar in the San Fernando Valley, and completion of the “Blended Option” upgrades on both sides, the trip is brought down to inside of 3hrs.

However … that is along one alignment, with the system still to be extended to Sacramento and San Diego. Merced would remain the jumping off point for the Sacramento leg of the San Joaquin, and would continue to benefit from the improvements to the Merced/Stockton alignment originally made for a loco-hauled extension of the HSR service. That part of the San Joaquin Merced to Sacramento forms a quite natural extension of the Capitol Corridor, forming a “horseshoe” route from Merced to Sacramento to Oakland to San Jose, and linking up with Express HSR service on both ends of the horseshoe.

Opening the Floor: Thoughts? Suggestions? Amendments?

Note that the standing rule of Sunday Train is that all topics on sustainable transport are on topic, so while you are encouraged to talk about the new developments in the California HSR projects or improving the “Slow Speed Rail” of Northern California or elsewhere … don’t be shy about raising any sustainable transport topic on your mind.

1 comments

Author

… I guess you could do the following as a QuickStep, but it would kind of miss the point …